Nature’s Garden and The Forager’s Harvest

Incredible, edible plants

Samuel Thayer’s field guides are bar none the best available resource for those interested in learning more about the foraging, preparation and consumption of wild plants. Unlike other guides, Thayer’s books, The Forager’s Harvest and Nature’s Garden, describe fewer plant species in greater depth–the kind of depth that is capable of inspiring just enough confidence when out foraging for a particular plant for the first time. Each species receives several pages of detailed descriptions and color photographs, with a specific focus on identifying characteristics, habitat, harvest, and preparation.

Prior to reading Thayer’s books my experience foraging was mycological in origin. For the past few years my nose has been stuck in various mushroom field guides that ran the gamut from awful to excellent. With that being the case, it’s immediately obvious just how valuable Thayer’s guides are. They are written by someone who has become an expert on every single plant featured, and by an author who knows how to convey critical details in text. It also doesn’t hurt that Thayer knows how to write something that is eminently readable.

The only downside to these two books isn’t really a downside. Thayer is a Wisconsin native and as such his expertise extends to plants native to the midwest. Luckily, most of these plants have a wide range. Living in Maryland, I’ve found many of the plants he mentions in both texts except for the truly regional plants like Wapato and Wild Rice. Those living west of the Rockies may have to look for more regional resources.

11/5/12Excerpt

From Forager's Harvest:

The first time you talk to a certain landowner, ask permission to harvest a specific plant that can be seen from the road; make it something like elderberries or butternuts that the landowner is likely to have heard of before. Offer to share your harvest with him. (Don't worry, he won't want any.) If the landowner was kind and the property seemed like a promising one that you'd like to return to, bring a gift of some foraged product, such as a jar of jam or jelly, as a thank you at a later date. After feeling assured that foraging really is a hobby of yours and that you're not up to anything else, the landowner will trust you more.

*

If you substitute a single wild ingredient in a familiar recipe and the result is disappointing, you may consider the recipe a failure but don't give up on the plant - it may be perfect for another dish. Be patient - it can take a while to figure out how to cook with an unfamiliar vegetable, especially those for which we don't have culinary traditions to guide us.

*

The Five Steps of Identifying Edible Plants

1. Tentative identification: You have located what you think is a certain plant.

2. Compare your plant to a reliable reference: Do this carefully, thoroughly, critically, and reasonably.

3. Double and triple check: Compare to several more reliable references

4. Find more specimens: Do this until you can effortlessly recognize the plant: it may take minutes, hours, days, or even years.

5. Assess contradictory confidence: Do you relay have it? Are you sure? Are you willing to bet your life? Would you proclaim it in front of a group of botanists?

Here's another good rule to follow: if you need to use a book to identify a plant, you are not ready to eat it.

*

The first time that you eat the plant, exercise some restraint. Cook it by itself and taste a small portion carefully. If it is bitter or otherwise distasteful, spit it out. This is an extremely important secondary line of defense. The tongue was designed to tell us which foods are safe and which aren't, and it does a remarkably good job of this. Most toxic plants taste terrible.

*

Most of our common spices and seasonings are toxic enough that consuming a few ounces would make a person very ill; in large enough doses they could be fatal. But who eats a few ounces of rosemary, mustard, or nutmeg? Who slurps down a glass of horseradish? What person, given alternatives, would choose to eat maize gruel as the main course of every meal for months on end? And who in the world gets locked in the chicken truck?

*

Riverside grapes in late August, just getting ripe.

*

Tartrate is present in all grapes but is highly concentrated in riverside grape and some of the other small-fruited species. Fortunately, it is easy to get rid of. Just let the juice sit in a container in the refrigerator or some other cool place for a day or two. The tartrate will settle to the bottom; you will recognize it because it forms an ugly grayish sludge. Pour off the good juice and then discard the tartrate sludge, which is usually about one-third of the volume of the grape juice. Never make anything from fresh-pressed small wild grapes without subjecting the juice to this purification process.

*

From Nature's Harvest:

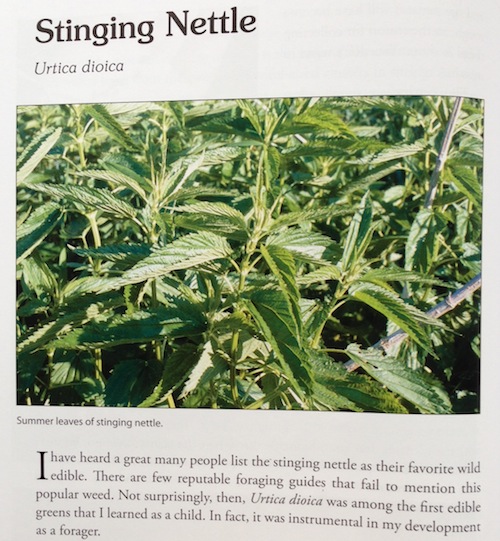

Stinging nettle is a tall and elegant perennial herb that grows in dense colonies connected by a network of narrow rhizomes. The stalks rarely exceed .4 inch (1 cm) in diameter. They are hollow and squarish with four deep grooves running their length, and rarely branch except where the plants have been injured. The stalks are typically 5-8 feet (1.5-2.5 m) tall at maturity. The bark of the stem is composed of strong fibers, which can easily be noted when the plant is broken. The main stem, petioles, and leaf surface bear stinging hairs, although these are generally absent from lower parts of the main stem after the plants reach full size.

The Forager's Harvest Samuel Thayer 360 p, 2006 $15 Available from Amazon Nature's Garden Samuel Thayer 512 pages, 2010 $16