Wild Colors * The Art & Craft of Natural Dyeing

Natural dyes

In our experiments with using natural dyes, Wild Colors has been the best introductory resource. A remarkable variety of plants can be used to dye fibers and cloths, and this book covers most of them, all in great color photos. I found the preparation instructions clear, and the color possibilities outlined inspiring. The guide is helpful for experimenting and making small batches.

But achieving deep colors consistently requires a lot more attention and knowledge. The finest steadfast colors may require 10 steps or more to process the natural ingredients. You’ll need J.N. Liles’ heavily researched tome on traditional methods, The Art & Craft of Natural Dyeing. It’s not well organized, but it is chock full of historical knowledge. An ease with chemistry will also help get the most from this exhaustive treatment of ancient dyeing skills.

12/10/12Excerpt

From Wild Colors:

Note: Bear in mind that it is not the amount of water used in the dye bath that affects the strength of the dye bath. The amount of water does not "dilute" the dye color: The strength of the dye bath is only affected by the amount of fibers added in relation to the amount of dye color present, as it is the color particles in the solution that have to be shared among the fibers being dyed.

*

Iron modifiers improve the fastness of most dyes and tend to make colors darker and more somber in tone. This iron modification process is called "saddening." It can turn yellows into olive-green and, if used with dyes rich in tannin, it can make colors dark gray and almost black. Add it to the dye bath or pot of water and stir it well. Put in the wetted fibers and simmer them for about five minutes. Iron usually take effect very quickly. It can also be applied without heat to many plant dyes. Rinse and wash fibers.

*

Washfastness

To test whether colored fabrics will stain or run, make two samples of each color. Sew one between two layers of undyed woolen fabric and another between two layers of undyed cotton fabric. Wash the samples, following the most likely procedure for the finishing item to see the degree of staining in the washing process.

*

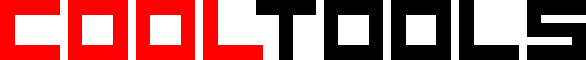

In Himalayan regions, species of rhubarb are particularly valued for their contribution to the dye pot. In parts of Tibet and Ladakh, and among Tibetan refugees in Nepal, rhubarb root is the most common source of yellow dye, and species of rhubarb have long been sought after locally. The roots are dried, chopped up, and ground into powder before use, and give strong, fast shades of yellow, gold, and orange.

*

Madder is one of the most ancient dyes and its existence can be traced as far back as the Indus civilization of around 3,000 BCE. Madder was cultivated throughout Europe and the Middle East, and the finest quality dyestuff came from Turkey, Holland, and France.

Madder root can also be simmered gently to extract the dye color but once the fibers have been added, the temperature should be kept well below a simmer to achieve clear reds. Simmering or boiling the dye bath will turn red colors browner and duller.

The best color results are often achieved if the pieces of madder root are left in the dye pot during the dyeing process.

*

Most of the colors produced from elder berries fade on exposure to light, but even the faded shades of pale lavender can be pleasing to the eye. Because of this characteristic, however, using fibers dyed with elder berries for tapestries or wall hanging is not recommended.

Sample excerpts, From The Art & Craft of Natural Dyeing:

About 1775, Dr. Edward Bancroft discovered a highly concentrated yellow dye in the inner bark of the American black oak tree (Quercus velutina). This was an extremely significant discovery since this dye, which he named "quercitron," was as fast or faster than weld, and it was much cheaper because the dye in weld is present in lower concentration. Thus, quercitron was to become the best natural yellow dye for the next century and was used commercially until about 1920.

*

Again, according to Pellew, in about 1908 a German dye chemist, Dr. Friedlander, spent the summer in Naples and collected approximately 12,000 Murex snails for dye extraction. From this quantity of snails he was able to extract about three-fourths of a gram of pure dye. Upon analysis, the dye proved to be 6, 6' dibromoindigo. Part of Friedlander's interest was in determining whether Tyrian purple was identical to thio-indigo red B, a synthetic indigo derivative that he had recently produced. The dye was not the same, and Tyrian purple was synthesized and used only for a short while.

*

A good black may be obtained by over dyeing a deep indigo blue with strong walnut. In this case sumac leaves or berries or a little tannin, and a little copperas, are added to the walnut. This works well on cotton, wool, or silk.