The Whole Earth Blogalog

Three recent books (From Counterculture to Cyberculture, What the Doormouse Said and Counterculture Green) plus a slew of newspaper articles have examined the influence of the Whole Earth Catalogs and periodicals upon on our culture. I am not the first to notice that the style of the Whole Earth Catalogs can be seen in the style of blogs and fan web sites. An article billed as the “oral history” of Whole Earth Catalogs just appeared in Plenty magazine. It says:

How did a publication with just a four-year run help shape a community so prolific that it went on to inspire Google, Craigslist, and the blogosphere; save six American rivers; and shape sustainable business practices as we know them today? Forty years after the first issue of the Whole Earth Catalog, this oral history of the publication, as told by those who made it and those who read it, tracks the long-lasting impact of a short-lived journal that altered the course of the world.

As the former editor-in-chief at Whole Earth, I spoke at length with the author. A few comments survived:

Kevin Kelly: For this new countercultural movement, information was a precious commodity. In the ’60s, there was no Internet; no 500 cable channels. Bookstores were usually small and bad; libraries, worse. The WEC not only gave you permission to invent your life, it gave you the reasoning and the tools to do just that. And you believed you could do it, because on every page of the catalog were other people doing it. This was a great example of user-generated content, without advertising, before the Internet. Basically, Brand invented the blogosphere long before there was any such thing as a blog.

I really mean that. This past week I had occasion to dip into the Updated Last Whole Earth Catalog. In my opinion, this was the apogee of all the many Whole Earth Catalogs. (And it was not the last one by a long shot.)

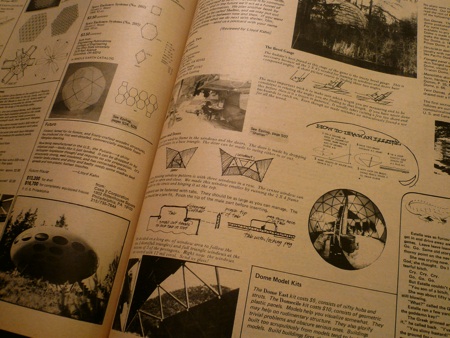

Geodesic Domes, in the Updated Last Whole Earth Catalog, 1975

As I read the dense, long reviews and letters explaining the merits of this or that tool, it all seemed comfortably familiar. Then I realized why. These missives in the Catalog were blog postings. Except rather than being published individually on home pages, they were handwritten and mailed into the merry band of Whole Earth editors who would typeset them with almost no editing (just the binary editing of print or not-print) and quickly “post” them on cheap newsprint to the millions of readers who tuned in to the Catalog‘s publishing stream. No topic was too esoteric, no degree of enthusiasm too ardent, no amateur expertise too uncertified to be included. The opportunity of the catalog’s 400 pages of how-to-do it information attracted not only millions of readers but thousands of Makers of the world, the proto-alpha geeks, the true fans, the nerds, the DIYers, the avid know-it-alls, and the tens of thousands wannabe bloggers who had no where else to inform the world of their passions and knowledge. So they wrote Whole Earth in that intense conversational style, looking the reader right in the eye and holding nothing back: “Here’s the straight dope, kid.” New York was not publishing this stuff. The Catalog editors (like myself) would sort through this surplus of enthusiasm, try to index it, and make it useful without the benefit of hyperlinks or tags. Using analog personal publishing technology as close to the instant power of InDesign and html as one could get in the 1970s and 80s (IBM Selectric, Polaroids, Lettraset) we slapped the postings down on the wide screens of newsprint, and hit the publish button.

This I am sure about: it is no coincidence that the Whole Earth Catalogs disappeared as soon as the web and blogs arrived. Everything the Whole Earth Catalogs did, the web does better.

But by the same equation, much of what the web is doing now, Whole Earth was doing then. Those folks who subscribed to the “feed” of CoEvolution Quarterly, the Whole Earth Review, and the WELL, got the blogosphere and user-created content 30 years early.

Living on the web decades before the internet was born; now that was a strange trip.