The End of Video as Evidence of Anything

Twenty three years ago, Stewart Brand, Jay Kinney and I wrote a cover story for the July 1985 issue of Whole Earth magazine called “The End of Photography as Evidence of Anything.” We noticed that high-end graphic computers were able to alter photos in such a way that they could convey any fantasy. At that time retouching on these machines was expensive (you paid a trained operator to do the retouching), so most of this fancy photo altering was done quietly for fashion, or magazine covers. No one was admitting to it, or talking about it. The alterations were stealth jobs, and therefore news to most people. Generally, photo alterations of this realistic type was so expensive, it was a big deal. It required a special dedicated main-frame computer, such as a $400,000 Scitex, to perform these tasks.

Our thesis — that with personal computers you could remake photography so realistically that it would not serve as evidence of reality — was based on the hunch that this rarified technology would someday soon be ubiquitous. At the time we were using command-line Kapro computers, and the Macintosh had just been released the year before. Photoshop was still very far away.

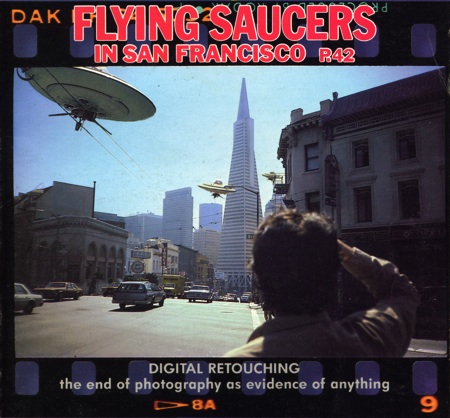

We fast-talked our way into getting some free time on a Scitex machine and had the technician “photoshop” some slides we had taken. We watched enthralled as he compiled a very convincing depiction of UFOs over San Francisco. This became the cover image for our essay on how photography was becoming unreliable. We argued that much like text, the only way to believe an image was to trust its source, rather than its content.

Of course nowadays, any kid could a better job retouching (just check out Worth 1000). But that was our point. Anyone would be able to photoshop. That’s what happened. Still-photography became unreliable. A still image now is no proof of anything.

Instead, in recent decades moving images — video — became the defacto evidence of truth. While a still image is suspect, a video of an event is usually granted credibility. “Don’t show us the photo, let’s see the video of Big Foot!” The more shaky, zoomy, nonchalant the video is, the more believable. In part because it is hard to retouch a shaky image. We are all aware of Hollywood special effects, which are completely seamless and realistic, but that is high-end expensive digital studio work. The cult movie Cloverfield, which mimicked the documentary style of an amateur camcorder but was crammed with wild cinematic fantasies, demonstrated once and for all that big money could fake video. In short, cinema got its Scitex machine.

The obvious next step is amateurs hacking the moving image with their lap tops. Once that becomes common place video is no longer evidence of anything.

I think we have crossed that threshold. In a very cool short video made by an aspiring filmmaker we can see the end, and the beginning of amateur cinematic fantasy. Ironically, the subject for this hack is Death Star over san Francisco. The still images don’t convey the visceral effect; watch the video.

The tools for this job were standard off-the-shelf items. From an interview on StarWarsBlog of the filmmaker Michael Horn:

I shot everything on my junkie DV camera, did motion-tracking and comping in After Effects, and basic sound design in Final Cut.