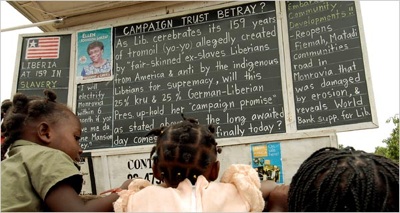

Blackboard Headlines

As the New York Times reported August 4, 2006, a clever man in Monrovia, Liberia found a way to serve the latest news to those who not only don’t have a RSS reader, nor a TV, they can’t even afford newspapers. He carefully writes headlines on a large community blackboard. This “newspaper” has the largest readership in the city.

In a country where wheelbarrows fill in for pickup trucks, water is carried on little girls’ heads instead of in pipes and gallon-size jars replace gas pumps, it is perhaps no wonder that a battered blackboard serves as newspaper and newsreel all in one.

Mr. Sirleaf prepares his news summaries and editorials in the newsroom of his shed and often uses visual aids for those who cannot read. The man behind what is surely the most widely read report here in the capital is a self-taught newshound with little more than a high school education and a nose for a good scoop.

He is Alfred Sirleaf, the 33-year-old managing editor of The Daily Talk, a white plywood shed trumpeting the latest headlines along Tubman Boulevard, one of the capital’s main thoroughfares.

For those who can read, Mr. Sirleaf writes up his succinct reports on the panels of his blackboard in a meticulous hand. “I try to write it really clear and simple so people can read it far away, even if they are driving by,” he explained.

For those who cannot read, Mr. Sirleaf has devised an ingenious system of symbols that transmit and sometimes subtly editorialize on the news. With the electricity story, hanging from the eaves of the newsstand on one corner was a kerosene lamp, next to an unlighted fluorescent bulb; on the other corner, there was a bag of drinking water, the kind young children sell to passers-by on the streets.

Every morning Mr. Sirleaf buys half a dozen newspapers and scours them for the most important developments. If they involve the United Nations peacekeeping force, for example, Mr. Sirleaf hangs up a blue helmet, the ubiquitous headgear for those forces everywhere. A chrome hubcap is the symbol for the president, who is called the “iron lady” of Liberian politics.

Inside his tiny newsroom he composes the day’s headlines on his blackboard, a meticulous process that can take a couple of hours. He carefully draws lines on the board with light-colored chalk to ensure that the words are written in a straight line. He uses a musty, tattered dictionary to check his spelling. In place of photographs he uses old campaign posters and other free handouts.

When a big story breaks, he has a painted “Breaking News” sign that he hangs like a shingle in front of his blackboard. The last time he used it was when Charles Taylor, a former president and warlord who started Liberia’s civil war, was arrested and turned over to a special court in Sierra Leone to be tried on war crimes charges.

He keeps on top of developments through a network of correspondents — friends who volunteer to be his eyes and ears — who send him reports via text messages to his cellphone. The shoestring operation brings him no income.

“I just manage along with whatever money I can find,” he said. Occasional gifts of cash and pre-paid cellphone cards keep him in business.