Jazz on Bones: X-Ray Sound Recordings

In the USSR and Eastern Europe in the 1950s underground night spots would play music pirated from the west. The only media they had were recorders etched into discarded X-ray film. I’ve long sought some images. Researcher Camille Cloutier pointed me to these, collected and posted by József Hajdú. Here’s what he says about them:

During the late 1930s and early 1940s the prevalent sound recording apparatus was the wax disk cutter. As a consequence of the lack of materials in the war-time economy, some inventive sound hunters made their own experiments with new materials within their reach.

I do not know the name of the inventor who first utilized discarded medical X-ray film as the base material for new record discs; however, the method became so widespread in Hungary that not only amateurs, but the Hungarian Radio made sound recordings on such recycled X-ray films.

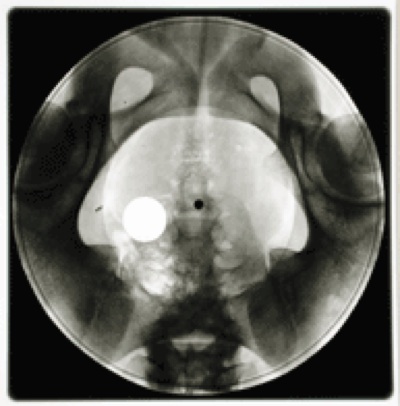

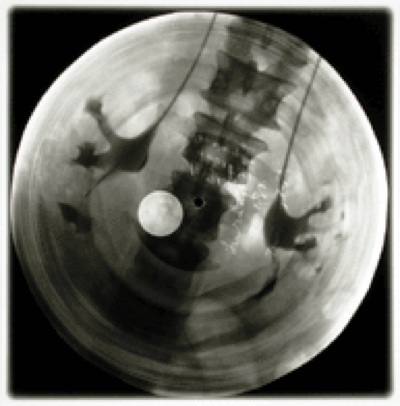

I felt that those X-ray record albums relate to our contemporary lives in many ways, especially when considering such terms as ‘multimedia’ or ‘recycling’. I copied the X-ray films with their engraved sound-grooves on photosensitive paper and made enlargements of certain details.

I was quite lucky to find a considerable amount of similar sound records in private collections. These are also interesting from the visual aspect. By utilizing different photographic processes, I created from them pictures meant to be exhibited in galleries.

In an online paper called The Historical Political Development of Soviet Rock Music, Trey Drake, at the University of California, Santa Cruz, offers further historical perspective on this street use of technology:

Owing to the lack of recordings of Western music available in the USSR, people had to rely on records coming through Eastern Europe, where controls on records were less strict, or on the tiny influx of records from beyond the iron curtain. Such restrictions meant the number of recordings would remain small and precious. But enterprising young people with technical skills learned to duplicate records with a converted phonograph that would “press” a record using a very unusual material for the purpose; discarded x-ray plates. This material was both plentiful and cheap, and millions of duplications of Western and Soviet groups were made and distributed by an underground roentgenizdat, or x-ray press, which is akin to the samizdat that was the notorious tradition of self-publication among banned writers in the USSR. According to rock historian Troitsky, the one-sided x-ray disks costed about one to one and a half rubles each on the black market, and lasted only a few months, as opposed to around five rubles for a two-sided vinyl disk. By the late 50’s, the officials knew about the roentgenizdat, and made it illegal in 1958. Officials took action to break up the largest ring in 1959, sending the leaders to prison, beginning an orginization by the Komsomol of “music patrols” that later undertook to curtail illegal music activity all over the country.

From Artemy Troitsky’s Back in the USSR: The True Story of Rock in Russia (1987, Omnibus Press):

The demand for pop and jazz recordings at the end of the fifties and beginning of the sixties was already enormous, while records and tape recorders were in catastrophically short supply. This led to the birth of a legendary phenomenon — the memorable records ‘on ribs.’ I myself saw several archive specimens.

These were actual X-ray plates — chest cavities, spinal cords, broken bones — rounded at the edges with scissors, with a small hole in the centre and grooves that were barely visible on the surface. Such an extravagant choice of raw material for these ‘flexidiscs’ is easily explained: X-ray plates were the cheapest and most readily available source of necessary plastic. People bought them by the hundreds from hospitals and clinics for kopeks, after which grooves were cut with the help of special machines (made, they say, from old phonographs by skilled conspiratorial hands).

The ‘ribs’ were marketed, naturally, under the table. The quality was awful, but the price was low — a rouble or rouble and a half. Often these records held surprises for the buyer. Let’s say, a few seconds of American rock’n’roll, then a mocking voice in Russian asking: “So, thought you’d take a listen to the latest sounds, eh?”, followed by a few choice epithets addressed to fans of stylish rhythms, then silence.

Both the shtatniki and beatnicki were few in number and their heyday was brief. The imitative, decorative style and American mannerisms they cultivated were way out of place in the early sixties, when Soviet youth was full of euphoric enthusiasm over the fliht of Yuri Gagarin, the Cuban revolution, and the programme proclaimed by Khruschev at the 22nd Party Congress wherein Communism would be achieved within the next two decades. Decadence and disaffection were completely out of style.

I’d love to find out more about this street use. Pointers welcomed.