The Seventh Kingdom

If we discovered life on another planet, the first thing we’d do is send a probe to begin a systematic survey of life on that world. Who knows what kind of weird organisms we’d find? Such a survey is a rational thing to do because the scientific payoffs would be huge. However we have yet to do that on our own home planet. According to various estimates we have discovered only between 1% and 30% of the living species on Earth. Numbers are hard to pin down, in part because the definition of a species gets fuzzy when talking about the most common form of life on earth: bacteria. However, the most reliable current estimate says we have discovered 3.7 million out of 30 million on the planet, or 10%. Any way we count it we are ignorant of the vast majority of the other organisms co-inhabiting this globe. Because humans have never done a systematic survey, nearly all these creatures have been discovered in serendipitous encounters by poking around here and there. Still, every year biologists finds new, strange and surprising species – often ones significantly different from what we already know.

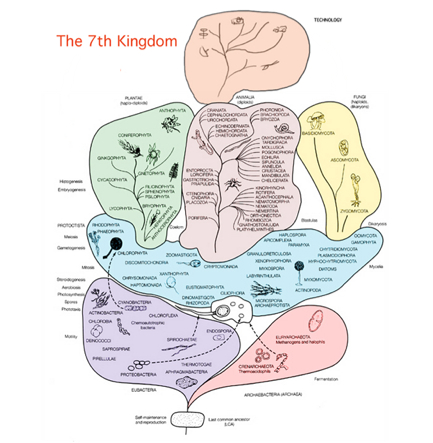

There may yet be surprises, but if we chart the varieties of life we have so far discovered on Earth, they fall into six broad categories. Within one of these six categories, or kingdoms of life, all species share a common bio-chemical process and genetic makeup. Six kingdoms is not the only way to group all species. Some researchers divide all into ten or eleven, some find 20 or more subgroups, and a few cling to the old three, four or five. But the current consensus holds that earthly life clusters into six major groups. Three of them are the tiny microscopic stuff: first, ancient primitive one-celled organisms, called archaea. Second, eubacteria, or common bacteria. And third, the protist, a diverse group of bacteria-like organisms that don’t fit into the other five categories. The other are the three kingdoms of organisms we normally see: fungi (mushrooms and molds), plants, and animals.

Every species in the six kingdoms, that is every organism alive on earth today, from algae to zebra, is equally evolved. Despite the differences in the sophistication and development of their forms, all living species have evolved for the same amount of time: 4 billion years; all have been tested daily, and have managed to adapt across hundreds of millions of generations in an unbroken chain. Many of these 3.7 million organisms have learned to build structures with their bodies or out of their own bodies. Termites build towering mounds up to 6 feet high, bacteria form dense aquatic mats, birds and some mammals build elaborate nests. These structures are built from plans hardwired into the organism’s genes. Without too much exaggeration, these artifacts can be thought of as an extension of their body, because like a body, they are a physical manifestation of a genetic code. Viewed this way, stuff that organisms make are extended bodies, or what science calls extended phenotypes. They are the stuff that genes build.

One of the species on earth – homo sapiens – makes a lot of stuff. Like termite mounds or colony bird nests, this stuff appears to be an extension of animal bodies. In broad strokes this is the stuff we call technology. Marshall McLuhan, among others, have noted that clothes are people’s extended skin, wheels extended feet, camera and telescopes extended eyes. Our technological creations are great extrapolations of the bodies that our genes build. In this way we can think of technology as an extended phenotype. During the industrial age it was easy to see the world this way. Steam-powered shovels, locomotives, television and the levers and gears of engineers were a fabulous exo-skeleton that turned man into superman.

A closer look reveals the problem with this view: the extended phenotype of animals is the result of their genes. They inherit the basic blueprints of what they make. Humans don’t. The blueprints for our stuff stem from our minds, which may create something none of our ancestors ever made or thought of. If technology is an extended phenotype of humans, it is a phenotype not of our genes, but of our minds. Clearly technology is not built by inheritable genes but by spontaneous ideas.

Technology is the phenotype of mind. It is the body for ideas. And what is remarkable about this body is that taken as a whole, it resembles the phenotype of biology. While there are some differences, the evolution of technology mimics the evolution of life. The two share many traits: Both evolutions move from simple to complex, from generalism to specialism, from uniformity to diversity, from individualism to socialism, from energy waste to efficiency, and from slow change to greater evolvability. Technology, like biology, moves toward greater diversity, socialism, complexity, efficiency and evolvability.

We might think of it as a type of life. Indeed, the way that specific technologies change over time fit a pattern similar to a genealogical tree of species evolution. One idea births many similar offspring ideas, which in turn lead to various related ideas for the next generation of technology. But instead of expressing the work of genes as in nature, technology expresses the ideas of our mind. Or, it has until lately.

The entire system of technology is now so complex that it forms a tangled ecology of ideas and devices which support each other. Human mind, so essential for its birth, play a decreasing role. Most of the communication traffic in the world is not humans speaking to humans, but machine speaking to machines. Computers are major co-designers of computers; it would be impossible to design the next generation of computers without computers. Artificial expert systems and embryonic AI are essential partners in large scientific experiments. Little new technology is able to thrive outside the ecology of other technology. There is a real sense in which the ideas underlying the phenotype of outward technology are no longer just the thoughts of humans. More and more technology is an extension of tiny, autonomous bacterial level impulses that originate in the technological system itself.

In this way, technology has become the seventh kingdom of life. In addition to archaea, protists, eubacteria, fungi, plants, and animals, we now need to add the technium. The technium branches off from the mind of the human animal, just as the deepest roots of the human branch off of the bacteria. Outward from this root flow primitive species of technology like hammers, wheels, screws, and refined metal, as well as domesticated crops. Over time the technium has evolved the most complex rarefied species like quantum computers, genetic engineering, jet planes, and the world wide web.

Life and technology traced back to a common stock. All seven kingdoms of life share the same remarkable ability to maintain disequilibrium, to increase extropy, and to accelerate evolution.