Ownership Is Use

In the late 1980s I was involved in a non-profit experiment in online life called the WELL. At that time “online” meant reading text messages zip across your green computer screen. Very few people were online, in part because you were charged hourly fees for connecting. Who wanted the meter running up many dollars per hour while you chatted? Larry Brilliant, who was then head of SEVA, a non-profit to eradicate curable blindness, and Stewart Brand, head of the Point Foundation, the publisher of the Whole Earth Catalogs, got together to hack an online service for the public at public prices. They were inspired by their experiences on a private network set up by the Western Behavioral Sciences Institute, and on EIES, an experimental system run by the New Jersey Institute of Technology. I was a member of EIES, too, and in fact, Stewart Brand hired me on the service in 1984. (I believe I may have been the first person ever hired online.)

In 1985 the WELL was started on the cheap, with a used VAX main-frame computer in an air-conditioned closet. The notion was to get everyone online. We’d start a sort of “People’s Online.” I was running the Whole Earth Catalog at the time and served as one of the directors of the WELL. Our design goal was to make access to the WELL free, or as near to free as we could. We believed regular people, folks like the readers of the Catalogs – teachers, organic farmers, ad reps – would find this “tool” worth the significant effort of learning how to use a programmer’s UNIX command line, which was necessary to log on. In the late 1980s there were commercial online systems interested in making as much money as possible by selling “content” to the users. The WELL, on the other hand, was aiming to “sell customers to each other.” The model was a phone company, which didn’t produce any content – and didn’t censor what was said either – but merely allowed its paying customers to connect with each other.

Cliff Figallo and John Coate in the VAX room

I still remember the day the WELL opened. Staring at that tiny green screen on our desks, we had the VAX humming in another room, the code kind of working, and the gates open. We let loose several dozen or so early users, online acquaintances from other online services. The hard disk was blank. We could make up any thread, topic, or conference we wanted. Anyone could. Start a topic and see who came. It was like staking out claims in the wilderness, building a town and hoping folks came and stayed. This pattern of self-directed growth would be replicated many times later on other online creations where the users build the “content”—like Wikipedia, Second Life, and in a large degree like the web itself.

And came they did. Even though the only thing you could do on the WELL was post messages in a conversational thread, or send IM-like messages to others online at the same time, or send email other WELL-ites (there was no messaging across services then), the hard disks began to quickly fill with the kind of comments, reporting, gossip, insight, and witty nonsense that has become very common on web forums. At the time it was intoxicating. In a kind of open-source way, the WELL allowed its UNIX-savvy users to create their own tools. Good tools got passed around and a few were even adopted system wide. The needed etiquette for harmonious behavior in this novel experience began to emerge. One WELL member named these shalls and shall-nots Netiquette, a name that stuck.

WELL posters who were very active, or very helpful with newbies, were granted moderating privileges, a small elevation in a very flat four-level hierarchy: users/moderators/WELL staff/WELL board. The higher levels did very little. All the WELL’s content, all of its marketing (word of mouth), much of its management, many of its tools, and the bulk of its value as a desired community came from the paying users. Within five years of very slow but steady expansion in the amount of content and members, the paying users of the WELL felt as if they owned the place. A vocal minority of members began agitating for a voice in the governance of the system. When SEVA’s half ownership of the WELL was sold to a private individual, there was even a quiet rebellion. The rebels tried to start their own community-owned online site, called The River.

A little appreciated consequence of user-created value is this deep urge to own what the group has been created. If you spend enough time in a place, that place begins to feel like home, your home. In the case of the WELL, we had instigated a peculiarly overly-simple policy to deal with copyright issues. The policy was stated on the log-in screen and said: “You own your own words.” The intent of the policy was to emphasize both aspects of ownership – its rights and duties – but almost everyone only remembered the rights of ownership, how no one else could use them, or move them, or even quote them with their permission. Stewart later said he wished he had written: “You are responsible for your own words,” but like many things, a license once given is almost impossible to retract.

For all its faults, the YOYOW policy (as it came to be known) worked. This small outpost of creative writing was one of many triggers which helped revive the art and pleasure of writing at a time when many educators were announcing the death of writing and reading in our culture. And it may have influenced later systems who had to grapple with the same problem of ownership. John Coate, the WELL staff member who served as the local sheriff in many disputes about word-ownership, pointed me to this interesting news:

In November 2006 the California Supreme Court reversed a lower court ruling and sided with one of the provisions of the 1996 Communications Decency Act (the part that was not thrown out like the censorship provision) that says a service provider – either an org, a company or an individual – is not liable for things that people say on their system. The person saying it however, does not escape accountability. In other words, You Own Your Own Words, in the arena of liability, is now the law of the land.

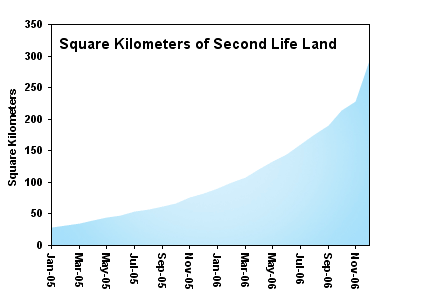

This YOYOW policy was a large part of why WELL dwellers felt a sense of ownership of the WELL itself. If the WELL was at its core words enlivened, then they owned the words. I was reminded of this urge to govern recently because of a not-dissimilar movement in Second Life. Second Life, like the WELL, is a user-created world. It’s a 3D virtual universe in the style of the vast multiplayer worlds of EverQuest, SimsOnline, and World of Warcraft. Inside you can visually navigate along streets, into houses and skyscrapers, and fly in three dimensions. But unlike other massively multiplayer online worlds (MMOGs), everything you see in this world, all its buildings, avatars, wilderness areas, are designed and constructed by other Second Lifers. It is an amazing achievement because the Second Life world is vast, complex, and unexpected. As of today the size of SL’s world is about 560 square miles, or 4.5 times the size of Manhattan.

Perhaps the most amazing achievement has been the way in way Second Life has become a parallel life, with many of same cultural inventions as real life. For instance the sale and resale of virtual products which customers manufacture, such clothing and real-estate, has produced a real multi-million dollar economy as large as many real cities. There is virtual sex and real love. There are real ads for virtual companies. The are actual laws for behavior. Wherever there is money being made and spent, love and sex on the loose, and laws made and broken, the need for government arises. Where there is property, there are disputes.

But who owns Second Life? Linden Labs, the mother of Second Life is a start up company which has spent many millions of dollars writing the software and hosting an ever-expanding array of disks to run this hugely intricate world. They deserve to be compensated. Of course anyone entering most commercial virtual worlds must sign a TOS (Terms of Service) or EULA (End-User Licensing Agreement) that essentially forfeits any claims of authorship or ownership. Technically the world owns your work. Still, the users make everything of value, and by their continuous maintenance and additions to their virtual creations (typically 20 hours per week), they are the key source of the growth in these fantasy universes. For these reasons, Second Life states clearly that users own the copyright of their creations. However users don’t own the data they generate in-world. And at first Second Life granted the right of reuse of creations within their world. This was controversial.

On the question of copyright and digital rights for music, text, pictures and movies, there’s a general agreement among the native netizens about what’s fair. Only a few die-hard corporations and industry lobby groups are considered clueless. But on the question of digital rights for the content producers within MMOGs, there’s widespread differences of opinion even among the users. When the good guys disagree on where the boundary is, then you have a real frontier.

In November 2006 a Second Life design team introduced an experimental “copy bot” which could clone user’s wares instantly and freely. An intricate virtual shirt which took you hours in SL to craft could be copied in seconds by some else using the copybot. A day later more than 100 vendors shuttered their stores in a Copybot Boycott to protest this erosion of their creative monopolies. These users strongly felt the policy should be “You own your own creations.” Other users, comfortable with dynamics of Napster, felt the world would be better, more creative, if sharing was optimized. Somewhat in response to this disruption, Linden Labs revised Second Life’s TOS to remove the legitimacy of unauthorized cloning.

Every MMOG produces certain artifacts that take a lot of time to acquire. A lot of time is what many workers in the developing world have. What these workers would rather have is some money from players in richer countries. They can get this loot by selling them virtual things they laboriously make in MMOGs. The buyers are eager to acquire artifacts with money instead of time. Since the exchange can happen electronically, anywhere in the world, large “gold farms” have erupted in places like Bulgaria, and China. Here students work for very little in digital sweatshops crafting powers and charms and architectural wonders for the virtual worlds of Second Life and other MMOGs. But do the gold farmers own what they make? In 2000 Sony Entertainment tried to squash the sale of items for its game EverQuest which were posted on eBay and Yahoo auctions, claiming they owned them. They were able to stop about $5 million worth of business, but it merely moved to second tier auction sites. A recent estimate put the resale value of gold-farmed items between $200-400 million. This is money Sony believes should circulate inside their own virtual economy.

In a fantasy world where you can be or make anything you can imagine, you might expect notions of property to be rewritten or re-imagined. However as Gregory Lastowka and Dan Hunter, two law professors at the University of Pennsylvania Law School note: “Virtual worlds all cleave to familiar real world expectations of property systems.” This normalcy is due to the fact that scarcities still reign in the virtual worlds, and “property interests emerge as a result of this scarcity.”

Although they mimic the rules of the real, are these virtual clothes, houses, cities really property at all? When property law experts examine the status of these creations they find that

…Any objection to the legitimacy of virtual property based on its intangibility is unfounded. Furthermore, they conclude that virtual property is justified by three of the major accounts of property that have informed legal decision-making in the western world since the industrial era – Bentham’s utilitarian theory, Locke’s labor-desert theory and Hegel’s personality theories. Their analysis shows that, in principle, all three theories support with qualification the claim that virtual entities and assets count as legitimate and real property. However, as Castronova points out, the results of this analysis do not confirm that virtual items must be treated as equivalent to real-world items – they simply show that ‘there are no prima facie grounds for dismissing the putative property rights of people who believe they own magic wands’ [1].

The conclusion is that virtual assets must be regarded as legitimate property. The only question is who owns this property? The citizens, or the host companies?

While the lawyers tug and stall, the citizens are getting restless. In July 2003, a bunch of activists staged a revolt against taxes applied by Second Life to virtual assets. The rebels anti-tax party started off as a protest but wound up as pure party, with surreal creatures, . As Peter Linden the official SL community director said afterward, “In Second Life, protests tend to be much more interesting as people can dress as they wish.”

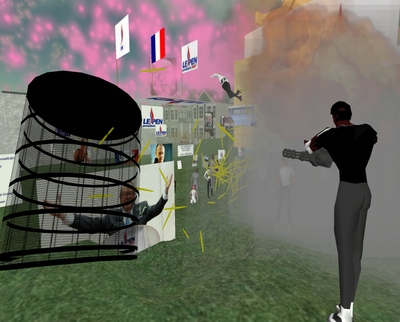

However, dissent breeds dissent. SL was shaken by a virtual riot in January 2007. When the French far-right anti-immigration organization Front National erected their headquarters in a mall on an obscure island in Second Life, protests began immediately. Placards, leaflets, and parades by opposition groups began. These escalated into an attack by anti-Front protesters who fired virtual pigs at Front headquarters. Crowds injected flickering holograms, “rez cages” (which trap avatars), and shock bombs which slowed the time to a crawl in the protest area. It felt like war.

Political unrest in virtual worlds was brought to my mind recently with the news that a band of rebels has been agitating for user democracy in Second Life. Because SL members own their virtual homes, and their adjacent stunning landscapes, as well as their many finely furnished mall developments to sell designer goods – because they own all this, they feel as if they should have some say in how their homelands are governed. They – mere paying customers – want a voice in the commercial company’s plan for them. They want to be treated as citizens. The motto of the rebels, who call themselves the Second Life Liberation Army might be “no ownership without representation.” So far, Linden Labs is not playing. So the dissidents have started a guerilla war in the virtual world. They stage pranks, disruptions, graffiti, and maybe more.

In my experience, the more technological systems become organic, real-like, and richly detailed in human experiences, the more they feel like our children. Once they are ours, we won’t let them go to strangers. Virtual worlds will feel this possessiveness first; more rebellions by the inhabitants can be expected. But later we’ll transfer this sense of possession to the artificial minds that we will train, and the little virtual creatures we will develop in environments like Spore. Whatever the law says about who owns the code and computing resources, ownership settles on use. Users will feel they own what they grow. Over time it is possible the law will move in that direction.