Technophilia

An acquaintance of mine has a teenage daughter. Like most teens in this century she spends her day texting her friends, abbreviating her life into 140 character hints, flinging these haikus out to an invisible clan of mutual texters. It’s an always-on job, this endless encapsulation of the moment. During dinner, while walking, on the toilet, lounging in bed, or in any state of wakefulness, to chat is to live. Like all teens, my friend’s daughter tested the limits of her parents’ restrictions. For some infraction or another, they grounded her. And to reinforce the seriousness of her misconduct, they took away her mobile phone. Immediately the girl became physically sick. Faint, nauseous, and so ill she couldn’t get out of bed. It was if her parents had amputated a limb. And in a way they had. Our creations are now inseparable from us. Our identity with technology runs deep, to our core.

According to psychologist Erich Fromm (and famed biologist E.O. Wilson) humans are endowed with biophilia, an innate attraction to living things. This hard-wired, genetic affinity for life and life processes ensured our survival in the past by nurturing our familiarity with nature. In joy we learned the secrets of the wild. The eons which our ancestors spent walking to find coveted herbs in the woods or stalking a rare green frog were bliss; ask any hunter/gatherer about their time in the woods. In love we discovered the boons each creature could provide, and the great lessons of hurt and healing organic forms had to teach us. This love still simmers in our cells. It is why we keep pets, and potted plants in the city, why we garden when supermarket food is cheaper, and why we are drawn to sit in silence under towering trees.

But we are likewise embedded with technophilia, the love of technology. Our transformation from smart hominid into Sapiens was midwifed by our tools, and at our human core we harbor an innate affinity for made things. We are embarrassed to admit it, but we love technology. At least sometimes.

Craftsmen have always loved their tools, birthing them in ritual, and guarding them from the uninitiated. As the scale of technology outgrew the hand, machines became a communal experience. By the age of industry, lay folk had many occasions to encounter complexifying technology larger than any natural organism they had ever seen and they began to fall under its sway. In 1900 the historian Henry Adams visited and revisted the Great Exposition in Paris, where he haunted the hall showcasing the amazing new electric dynamos, or motors. Writing about himself in the third person he recounts his initiation:

To Adams the dynamo became a symbol of infinity. As he grew accustomed to the great gallery of machines, he began to feel the forty-foot dynamos as a moral force, much as the early Christians felt the Cross. The planet itself seemed less impressive, in its old-fashioned, deliberate, annual or daily revolution, than this huge wheel, revolving within an arm’s-length at some vertiginous speed, and barely murmuring — scarcely humming an audible warning to stand a hair’s-breadth further for respect of power — while it would not wake the baby lying close against its frame. Before the end, one began to pray to it.

Each summer tens of thousands of enthusiasts make a pilgramage to a nearby town along the Pacifica coast where I live to collectively bestow affection upon beautiful machines. The love-in, called Dream Machines, draws smitten fans of self-powered vehicles: cars, airplanes, steam engines. Rows of restored 1950s Chevys, and vintage Packards, in candy-color deliciousness woo their admirers. Rare species of airplanes, rivets gleaming, recline in a field, their painted propellers and exposed engines beckoning. A parade of oddly mutant motorcycles stream by. Behind one roped-off area a dozen old guys in overalls and greasy baseball caps tend noisy, hissing contraptions. This is the steam-powered zoo. Unlike modern machines, the innards of steam machines are visible, a kind of living transparency which solicits admiration for their mechanical honesty. One capped fellow demonstrates an insanely dangerous steam-powered cross-cut saw. Its naked teeth, as long as fingers, rake across a sacrificial log in a reptilian frenzy. The onlookers nod in approval.

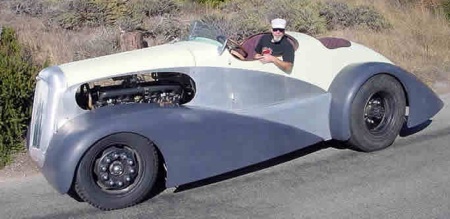

I was there to witness the love. I was born lacking the normal male gene for car-madness. I am oblivious to the subtle differences in automobiles; I can’t tell one sedan from another. I don’t even know the model of the old van I drive. But I came to see others venerate classic technology. So it was weird to discover in one corner of this teeming rendezvous, three magnificent machines that snagged my soul as I tried to walk by. In an instant I was bewitched. I felt these were the most intoxicating vehicles I had ever seen. I had no idea what they were. A metal circular logo affixed to the front grill on each declared that they were Blastolenes.

Blastolenes are custom-built fantasies. They are oversized car-like monsters that retained the rough proportions of ordinary vehicles, only at a disturbing larger scale. Imagine your car three times its current size. One Blastolene was strapped down to a flat bed truck as if it were a trophy wild gargantuan captured by hunters, and it might bust its chains at any moment and zoom off. Like many vehicles it was animalish: the Blastolene’s exposed circulatory pipes suggested guts, its rounded wheel cases were muscular hunches, and its chrome tie rods were obviously bones. People crowded around, sighing in satisfaction at its remarkable beauty. I was seized with a deep affinity for the creature.

The second Blastolene on display was a convertible sedan built around a hulking M7 Patton Tank motor. The motor emitted percussions rather than sound. Its gigantism was irresistible. I suddenly realized that for 40 years I had been driving baby cars; this was the daddy car. Timidly creeping up to it (can I touch it?), I felt a childlike awe. I could feel its abnormal density; the solid gravity pulling me in toward it, yet its intimidating scale, like an elephant, warning me away.

No doubt much of the attraction of these machines are the way they ape, so to speak, animal life. Maybe our technophilia is merely biophilia in disguise. But some of the magnetism that draws us to them is also due to the dynamo that peeks from their interior. Its rotational energy twirls us. Many decades ago California writer Joan Didion made a pilgrimage to the Hoover Dam, a trip she recounts in her anthology, The White Album. She, too, felt the heart of a dynamo.

Since the afternoon in 1967 when I first saw Hoover Dam, its image has never been entirely absent from my inner eye. I will be talking to someone in Los Angeles, say, or New York, and suddenly the dam will materialize, its pristine concave face gleaming white against the harsh rusts and taupes and mauves of that rock canyon hundreds or thousands of miles from where I am.

…Once when I revisited the dam I walked through it with a man from the Bureau of Reclamation. We saw almost no one. Cranes moved above us as if under their own volition. Generators roared. Transformers hummed. The gratings on which we stood vibrated. We watched a hundred-ton steel shaft plunging down to that place where the water was. And finally we got down to that place where the water was, where the water sucked out of lake Mead roared through thirty-foot penstocks and then into thirteen-foot penstocks and finally into the turbines themselves. “Touch it,” the Reclamation man said, and I did, and for a long time I just stood there with my hands on the turbine. It was a peculiar moment, but so explicit as to suggest nothing beyond itself.

…I walked across the marble star map that traces a sidereal revolution of the equinox and fixes forever, the Reclamation man had told me, for all time and for all people who can read the stars, the date the dam was dedicated. The star map was, he had said, for when we were all gone and the dam was left. I had not thought much of it when he said it, but I thought of it then, with the wind whining and the sun dropping behind a mesa with the finality of a sunset in space. Of course that was the image I had seen always, seen it without quite realizing what I saw, a dynamo finally free of man, splendid at last in its absolute isolation, transmitting power and releasing water to a world where no one is.

Of course dams inspired dread and disgust as well as awe and admiration. Soaring, breathtaking dams frustrate the return of single-minded salmon and other spawning fish, and they indiscriminately flood homelands. In the technium revulsion and reverence often go hand in hand. Our biggest technological creations are like people in that way; they elicit our deepest loves and hates. On the other hand no one has ever been revolted by a cathedral of redwoods. In reality no dam, even Hoover dam, is eternal under the stars since rivers have a mind of their own; they pile up silt behind the dam’s wedge so that eventually their waters can crawl over it. But while it stands, the artificial wins our admiration. We can identify with the dynamo revolving forever, as we feel our living hearts must do.

Passions for the made run wide. Almost anything manufactured will have adoring fans. Cars, guns, cookie jars, fishing reels, tableware, you name it. Their fans lavish attention by comprehensively collecting all variants of the technology, or modifying the standard form, or by imitating their own version. Not surprisingly, fans of a feather gather together. I tallied up the number of online forums for manufactured items commonly adored. One might think of these as churches. I found over 40,000 online congregations dedicated to honoring various cars, more than 10,000 different fan groups enamoured of motorcycles, 6,000 assemblies really into boats, 5,000 fellowships serving avid gun owners, and 1,000 denominations obssessed with all types of cameras. The list for other artifacts, tools, and machines commanding their own smitten followers would run into the hundreds.

MIT sociologist Sherry Turkle calls a particular specimen of technology that is revered by an individual an “evocative object.” These bits of the technium are totems that serve as a springboard for identity, or for reflection, or for thinking. A doctor may love his/her stethoscope, as both badge and tool; a writer might cherish a special pen and feel its smooth weight pushing the words on their own; a dispatcher can love his ham radio, relishing its hard-won nuances, as a magical door to other realms that opens to him alone; and a programmer can easily love the root operating code of a computer for its essential logical beauty. Turkle says, “we think with the objects we love, and we love the objects we think with.” She suspects that most of us have some kind of technology that acts as our touchstone.

I am one of them. I am no longer embarrassed to admit that I love the internet. Or maybe it’s the web. Whatever you want to call the place we go to while we are online, I think it is beautiful. People love places, and will die to defend a place they love, as our sad history of wars prove. Our first encounters with the internet/web portray it as a very distributed electronic dynamo – a thing one plugs into — and that it is. But the internet is closer to the technological equivalence of a place. An uncharted territory where you can genuinely get lost. At times I’ve entered to web just to get lost. In that lovely surrender, the web swallows my certitude and delivers the unknown. Despite the purposeful design of its human creators, the web is a wilderness. Its boundaries are unknown, unknowable, its mysteries uncountable. The bramble of intertwined ideas, links, documents, and images create an otherness as thick as a jungle. The web smells like life.

It knows so much. It has insinuated its tendrils of connection into everything, everywhere. The net is now vastly wider than me, wider than I can imagine, so in this way, while I am in it, it makes me bigger too. I feel amputated when I am away from it.

I find myself indebted to the net for its provisions. It is a steadfast benefactor, always there. I caress it with my fidgety fingers; it yields up my desires, like a lover. Secret knowledge? Here. Predictions of what is to come? Here. Maps to hidden places? Here. Rarely does it fail to please, and more marvelous, it seems to be getting better every day. I want to remain submerged in its bottomless abundance. To stay. To be wrapped in its dreamy embrace. Surrendering to the web is like going on aboriginal walkabout. The comforting illogic of dreams reigns. In dreamtime you jump from one page, one thought, to another. First on the screen you are in a cemetery looking at an automobile carved out of solid rock, the next moment, there’s a man in front of a black board writing the news in chalk, then you are in jail with a crying baby, then a woman in a veil gives a long speech about the virtues of confession, then tall buildings in a city blow their tops off in a thousand pieces in slow motion. I encountered all those dreamy moments this morning within the first few minutes of my web surfing. The net’s daydreams have touched my own, and stirred my heart. If you can honestly love a cat, which can’t give you directions to a stranger’s house, why can’t you love the web?

Our technophilia is driven by the inherent beauty of the technium. Admittedly, this beauty has been previously hidden by a primitive phase of development that was not very pretty. Industrialization was dirty, ugly, and dumb in comparison to the biological matrix it grew from. A lot of that stage of the technium is still with us spewing its ugliness. I don’t know whether this ugliness is a necessary stage of the technium’s growth, or whether a smarter civilization than us could have tamed it earlier, but the arc of technology’s origins from life’s evolution, now accelerated, means that the technium contains all of life’s inherent beauty – waiting to be uncovered.

Technology does not want to remain utilitarian. It wants to become art, to be beautiful and “useless.” Since technology is born out of usefulness, this is a long haul. Robots will proliferate in a million different varieties and levels. Most will never be as smart as a grasshopper, and only few droids will surprise us with their intelligence. But the goal of every robot, and every machine and tool, is to exist for its own sake. To exist not only because it is useful, but because its existence is beautiful. There is evidence of that back on the fields of the Dream Machines, in the rows of mechanical glamour. While the Blastolene and lollipop 1950s Chevys are potentially useful – as transport – few are actually used that way. They are coddled, nursed and nurtured, repaired and improved, adored and honored, and sculpted into longevity by the sheer love of their innate beauty. They are art.

Today, at the start of the 21st century, there are tens of million species of tools and technologies at loose in the world. Assuming a modest increase of only 5% additional new tools and kinds of artifacts every year, by the end of the century our planet will be overrun by manufactured possibilities. Our own human needs are not expanding at this rate. The continual rise in technological variety is propelled by the needs of other technologies. You have a house, then you get a car. Now your car needs a house, too. It doesn’t have hands like you do, so it needs a garage-door opener for its house. It needs check up equipment to keep it healthy, and add ons to keep it comfortable. The same goes for other kinds of hardware. Handheld devices need jackets, houses need paint, computers need peripherals. I estimate that about half of the denizens of the technium are technologies serving other technologies. If you remove a keystone technology from your home – say the computer – how many other devices and equipment would immediately become redundant? Remove your car, and what else can go? Remove your stove, and then count the pieces of gear no longer needed.

But we won’t let these subordinate technologies go, based on the evidence so far. We don’t “need” a lot of what we maintain. We keep specific technology around not only because it may be useful, but because we like to have it around. The gear, devices, networks form an interdependent ecosystem of interrelated parts, and we have a technophilia for its survival. We love the jungly mesh of the technium, and the way we can lose ourselves in it. We rebel at the negative costs of this interrelatedness, and its negative externalities such as pollution (global warming is a type of pollution), but we have a deep affinity for its web. We continue to manufacture new ideas and new artifacts, not because we always need them, but because the technium needs them, and because we find the technium attractive.

Most evolved things are beautiful, and the most beautiful are the most highly evolved. Cities display this principle clearly. Newborn, unrefined cities lack depth, and so, throughout history humans find new cities ugly. The first few versions of London were considered heinous eye sores. But over generations, every urban block in that city and all others are tested by daily use. The parks and streets that work are retained; those that fail are demolished. The height of buildings, the size of a plaza, the rake of an overhang are all adjusted by variations until they satisfy. But not all imperfection is removed, nor can it be since many aspects of a city – say the width of streets — cannot be changed easily. So urban workarounds and architectural compensations are added over generations. Additionally, every available opportunity to build within a city is grabbed. The tiniest alley way is utilized for public space, the smallest nook becomes a store, the dampest arch under a bridge filled in with a home. Over centuries, this constant infilling, ceaseless replacement and renewal, and complexification – or in other words, evolution — creates a deeply satisfying esthetic. The most beautify places are those that reveal layers of time. They accrue forms uniquely fitted to that place. Every corner in a city carries the long history of the city embedded in it like a hologram, glimpses of which unfold as we stroll by it.

The superb special effects magicians working for Hollywood discovered how to exploit the principle of evolutionary beauty when filming made-up worlds. Their fantastic cities and convincing props of the future are in reality new items, having been imagined only days earlier. To give them the convincing heft of reality, and the attractive richness we associate with beautiful things, the effects wizards devise a layered evolutionary backstory for each item or place. Model makers layer on “greeblies,” or intricate surface details that reflect a fictitious past history. This artificial evolution produces objects and places that exhibit what George Lucas calls the “used future.” For instance a detailed ray gun arrives at its current design via an imaginary backstory in which its predecessors were once longer and powered by a different energy source; the gun thus contains vestigial ridges and tubes. We feel authenticity. A backstory assumes that a 22nd century city had been bombed in a previous age; its earlier primitive steel ruins under gird the foundation of recent crystalline towers. It looks beautiful.

Evolution is not just about complications. One pair of scissors can be highly evolved, and beautiful, while another is not. Both scissors entail two swinging pieces joined at their center. But in the highly evolved scissors, the accumulated knowledge won over thousands of years of cutting is captured by the forged and polished shape of the scissor halves. Tiny twists in the metal hold that knowledge. While our lay minds can’t decode why, we interpret that fossilized learning as beauty. It has less to do about smooth lines and more to do about smooth continuity of experience. The attractive scissors, or beautiful hammer, or gorgeous car, carry in their form the wisdom of their ancestors.

Not all stuff will attract our emotions, and the same life-likeness and sentience will often infuriate us. Professor Sherry Turkle has spent her professional life studying (and worrying) about the human propensity towards technophilia. For the past three decades MIT engineers have designed a series of robots that increasingly take on attributes of human personality. The latest one is called Nexi. When Nexi is not on, the researchers pull a curtain around it. One day a student came in late to work on the robot, but found no one else around, so she pulled back the curtain. She was startled and confused to find Nexi blindfolded. What did it mean? As Turkle relates the story: “It raised the question in the mind of the perplexed student, are we protecting the people around the robot, or are we protecting the robot? The blindfold immediately brought up the fantasy of torturing the robot. You know, if it’s alive enough to need a blindfold, then maybe it’s alive enough to be tortured.”

We are so eager to love technology that Turkle is worried this love blinds us. In her laboratory Turkle observes how ordinary people feel about anthropic technology. She has been surprised at how little encouragement humans need to surrender love for machines. The merest suggestion of human-like eye movement, the tiniest hint of active eyebrows, and the roughest ready smile on an otherwise obviously metal machine can make a person melt before it. Even feel bad about turning it off. Humans will treat any minimally anthropomorphized droid like it not only deserves our affections, but in some strange way is returning our love. That worries Turkle because she is concerned whether we will diminish our own humanity in order to match this minimal humanity we spy in our creations. If we let robots take care of the elderly as they want do in Japan, will the elderly become robot like to meet them? As computer scientist Jaron Lanier, another worrier of technophilia, puts it: “We make ourselves stupid in order to make computers seem smart. I don’t worry about computers getting intelligent, I worry about humans getting dumber.”

In the future, we’ll find it easier to love technology. Machines win our hearts with every step they take in evolution. Like it not, anthropic robots (at the level of pets at first) will gain our affections, since even minimal life-like ones do already. The internet provides a hint of the maximal passion possibilities of the technium. The global internet’s nearly organic interdependence, and emerging sentience make it wild, and its wildness draws our affections. No human can turn away from the trick of anthropomorphism, and not be seduced by the humanity we project onto look-alikes, but the attraction of highly evolved technology is not only in its reflection of our faces. We are deeply attracted to its beauty, and its beauty resides in its evolution. Humans are the most highly evolved organs we have experienced, so we fixate on imitations of this form (quite naturally), but our technophilia is fundamentally not for anthropy, but for evolution. Humanity’s most advance technology will soon leave imitation behind and create obviously non-human intelligences, and obviously non-human robots, and obviously non-earth-like life, and all these will radiate an attractiveness that will dazzle us.

As it does, we’ll find it easier to admit that we have an affinity for it. In addition the accelerated arrival of tens of millions more artifacts will deposit more layers onto the technium, polishing existing technology with more history, and deepening its embedded knowledge. Year by year, as it advances, technology, on average, will increase in beauty. I am willing to bet that in the not-too-distant future the magnificence of certain patches of the technium will rival the splendor of the natural world. We will rhapsodize about this technology’s charms, marvel at its subtlety, travel to it with children in tow, to sit in silence beneath its towers.

And this is as it should be because technology wants to be loved.