How to Thrive Among Pirates

Shangri-La is the official name of a small Chinese town in a mountainous valley on the edge of the Tibetan plateau. Formerly called Zhongdian, the town was renamed Shangri-La by local businessmen with the blessings of the national government in order to spur tourism. Who would not want to visit Shangri-La? I’ve been twice, and sorry to say, it is no Shangri-La. But on my last visit there a pristine 6-inch layer of snow in April covered the normally dusty and dilapidated old town, and in this clean robe it actually looked picturesque.

Old guy on the main street of Shangri-La.

For hundreds of years this frontier town has been an overnight stop for travelers along the winding road from the agriculturally rich highlands of Yunnan to the dry wind-swept lands of Tibet. The shops along the main street of Shangri-La today sell an exotic assortment of household goods to a steady stream of Tibetan and minority farmers trudging in from the countryside. A hundred one-room shops along a drab main street offer sturdy leather boots, brightly woven carpets, farm hardware, rugged horse blankets, hot water thermos bottles, solar battery rechargers, cheap iron tools, and fancy striped fabrics and ribbons. Mixed among this traditional ware were dozens of shops that sold nothing but DVDs for thousands of movies. A few of the shops had a greater selection of movies for sale or rent than your local Blockbuster. Some of the thousands were Hollywood hits, some were Hong Kong kungfu episodes, or Korean series, but most were Chinese-made films. Almost all of the discs were cheap (less than $3) pirated copies. The new digital “freeconomy” where copies flow without payment is not just a trait of cosmopolitan cities; information wants to be free even in the most remote parts of the globe.

I was in China, in part, to answer this simple question: how does the China film industry continue to produce films in a land where everything seems to be pirated? If no one is paying the filmmakers, how (why) do they keep producing films? But my question was not just about China. The three largest film industries in the world are India, Nigeria and China. Nigeria cranks out some 2,000 films a year (Nollywood), India produces about 1,000 a year (Bollywood) and China less than 500. Together they produce four times as many films per year as Hollywood. Yet each of these countries is a haven, even a synonym, for rampant piracy. How do post-copyright economics work? How do you keep producing more movies than Hollywood with no copyright protection for your efforts?

This question was pertinent because the rampant piracy in the movie cultures of India, China and Nigeria seemed to signal a future for Hollywood. Here in the West we seem to be headed to YouTubeland were all movies are free. In other words we are speeding towards the copyright-free zones represented by China, India and Nigeria today. If so, do those movie industries operating smack in the middle of the cheap, ubiquitous copies flooding these countries have any lessons to teach Hollywood on how to survive?

The answers uncovered by my research surprised me. My first surprise was the discovery that in each of these famously pirate-laden countries, piracy is not really rampant – at least not in the way it is usually portrayed by copyright police. Piracy of imported (i.e., Hollywood) films is rife, but locally produced films are pirated to a lesser degree. The reasons are complex and subtle.

Most Nollywood films are completed in two weeks.

The first consideration is quality. Nigerian films are a unique blend of a soap-opera and a Bollywood musical; there’s a bunch of talking then a bunch of dancing. To call some of the Nigerian films low-budget would be to insult low-budget films. Many of the thousands of Nigerian movies are more like no-budget films. But even big-budget Bollywood films are cheap compared to Hollywood, so the total revenue needed to sustain their production is much smaller than Hollywood blockbusters. Naturally the smaller the costs, the less needed to recoup the expenses. For some films even a trickle of revenues may be enough.

Posters on the Lagos street (via Esquire)

But more importantly, low quality is not just a trait of illegal stuff. In Nigeria, particularly in the poorer north, a vast network of small-time reproduction centers serve up copies of films for an audience of many millions. Originally an underground network of copy centers replicated VHS tapes; now the network pumps out optical disks. In the former days of VHS tape copies, the official versions had much better printed covers. These readable and brightly colored covers were their chief selling point, and printing the covers was the bottleneck at which the film industry exerted their policing. But these days in Nigeria, as in the rest of the developing world, movie disks are usually VCDs (video CDs) rather than DVDs. Although lower in resolution, VCDs are easier to duplicate, with cheaper blanks, and in a quality that is “good enough” on a cheap TV screen. These copies are rented out for a few cents from small dusty shacks. But often the cheap VCDs which rent for pennies are “legitimate” – duplicated under an arrangement with the movie producer. The filmmakers and the duplicators have cleverly reduced the price of legitimate discs near to the price of pirated disks. In fact the same operators will usually duplicate both. Since the legitimate disks aren’t that much more expensive than illicit ones, distributors have less incentive to bother with lower-quality pirated versions.

In addition the financing of films in Nigeria is closely aligned with the underground economy. Investing in a film is considered a smart way to launder money. Accounting practices are weak, transparency low, and if you are a thug with a lot of cash “to invest” you get to hang around movie stars by bankrolling a film. In short the distinction between black market disks and official disks generated with black market money is slim.

Nigerian filmmakers look to two other sources of revenue for their trickle of money: theaters and TV. Theaters in Nigeria offer a very precious commodity for very cheap ticket: air conditioning for several hours. The longer the film the better the deal. Theaters also offer a superior visual experience to watching a tape of VCD on an old television. You might actually be able to read the subtitles, or hear the background sounds. The full theatrical experience of a projected film is simply not copyable by a cheap optical disk. So box office sales remain the major revenue support for a film. As Nigeria’s nascent TV industry grows, its appetite for content means there is additional revenues for broadcasting films on either airways or cable systems.

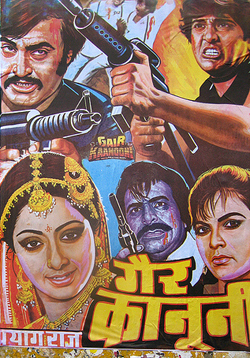

Bollywood wall poster in Rajastan (via Meanest Indian)

Bollywood is likewise supported by air-conditioning. Few Indians have aircon in their homes, fewer own air-conditioned cars. Mid-afternoon in the summer you really don’t want to be anywhere else except in a cool theater for several hours – which is why Bollywood films can go on forever. You can sell a lot of movie tickets this way, even though someone could get the same movie for almost free as a DVD on the steaming hot, dusty street one block away.

Like Nigeria, India has a similar mixture of piracy and legitimacy in its film industry. Bollywood and mafia money are famously intertwined. In terms of money laundering, tax-avoidance, and covert money flows, the entire film industry is a gray market. The behind-the-scenes people making illegal copies of films also make the legal copies. And prices for legit and pirated versions are almost at parity.

So why even bother with pirated movies? Because India has had a very draconian censorship policy for official studio films. Their famous “no kissing” rule is but one example. This censorship has pushed niche films to the underground where they are served by the piracy network. If you want something independent, racy, out of the ordinary, or simply not in the mainstream, you are forced to patronize the pirates. This includes the filmmakers as well as the audience. If you produce an avant-garde film how else to get it seen? Cheap duplication on the street is the way a filmmaker will get his art out, further blurring the distinction between legit and illegal. As in Nigeria, this convergence means the purchase price of an official VCD may not be much more than a pirated version, about US$3. In effect Indian filmmakers see these low disc prices as advertising to lure the masses into cool theaters to see the latest releases on the glorious big screen. The hi-touch factor of the theaters is the reward for paying, and the pirated versions are the tax or costs for getting attention.

China also has a censorship problem. Big budget films are subsidized by the government, and live off theatrical release. In fact getting screen time in theaters is heavily politicized. Independent films can’t get booked in the limited number of theaters, so they get to their audience on optical disks. And if a viewer wants to watch a film not produced by state-sponsored studios they have to find one on the streets. As in India and Nigeria, the price of legitimate copies are close to pirated, so for consumers there is no difference between the two. You can rent a copy of either type for about 25 cents a night.

The third leg supporting indigenous film industries in lands without copyright enforcement is television. Particularly cable television. Television is a beast that must be fed every hour of the day, and the industry insiders I spoke to in India, China, and Nigeria all saw a television spot as a legitimate destination for independent artists. The sums paid for work appearing on cable TV were not large, but they were something. Because television runs on attention and is supported by ads, the issues of piracy are sidestepped. For some producers pirated discs on the street create an audience, which might translate into a call to run their work on TV, or else prompt an invitation to produce something new.

Where indigenous filmmakers feel the sting of piracy is not within their own countries but in the very active export market. Nigerian films are watched throughout African and in the Nigerian diaspora; likewise Indian films are early sought out throughout South Asia and the Mid-East and in deep Indian communities in the West. Chinese films are watched in East Asia. Most of this market is served by pirated editions, depriving the filmmakers of potential international income. In this way these ethnic film industries share the same woes as Hollywood. But in their home turf, where the success of a film really lies, piracy is a different animal than the specter predicted by Hollywood.

Back on the gritty streets in Shangri-La I went looking for that utopian dream: a DVD of a first run movie for a dollar. That dream was too optimistic, even for Shangri-La, but I did find a copy of the latest Harry Potter movie (with Chinese subtitles) for $3, and upon close inspection it sure looked like a legit version. Clean design, Chinese style, crisp printing on the box, no typos, official looking holograph seal, etc. It was most probably illegal, but who knows? It would take a lot of research to determine its true origins, and for most consumers, like me, a moot question since every DVD vendor in town seemed to have the same inventory of mixed goods, all priced about the same.

What do these gray zones have to teach us? I think the emerging pattern is clear. If you are a producer of films in the future you will:

1) Price your copies near the cost of pirated copies. Maybe 99 cents, like iTunes. Even decent pirated copies are not free; there is some cost to maintain integrity, authenticity, or accessibility to the work.

2) Milk the uncopyable experience of a theater for all that it is worth, using the ubiquitous cheap copies as advertising. In the west, where air-conditioning is not enough to bring people to the theater, Hollywood will turn to convincing 3D projection, state-of-the-art sound, and other immersive sensations as the reward for paying. Theaters become hi-tech showcases always trying to stay one step ahead of ambitious homeowners in offering ultimate viewing experiences, and in turn manufacturing films to be primarily viewed this way.

3) Films, even fine-art films, will migrate to channels were these films are viewed with advertisements and commercials. Like the infinite channels promised for cable TV, the internet is already delivering ad-supported free copies of films.

Producing movies in a copyright free environment is theoretically impossible. The economics don’t make sense. But in the digital era, there are many things that are impossible in theory but possible in practice – such as Wikipedia, Flickr, and PatientsLikeMe. Add to this list: filmmaking to an audience of pirates. Contrary to expectations and lamentations, widespread piracy does not kill commercial filmmaking. Existence proof: the largest movie industries on the planet. What they are doing today, we’ll be doing tomorrow. Those far-away lands that ignore copy-right laws are rehearsing our future.