The Future Doesn’t Matter

The future is less fashionable than it was only 10 years ago. It is no where as romantic as it was in the final decades of the last century. You could make an argument that the popularity of the future peaked in the 1950s, and has been on a steady decline since then. My feeling is that since the dot.com bust of 2001, the future is far less cool. It doesn’t seem to matter as much.

Serious interest in the future is historically very recent. It did not begin until significant change occurred within a lifetime. Before then the world you were born into was the same one you grew old in. There was no need to contemplate the “future.” It was just more of the same.

But once the pace of change became visible to an individual, interest and concern about what was next became almost a survival need. Science fiction began as a literary genre at the same time that serious change outpaced one’s life. During the industrial and digital revolutions, you needed to discern the future because that was were you were going to spend the rest of your life.

But then something weird happened in the first few years of this decade. The pace of change became so fast that it outpaced contemplation. The future became harder to predict, and exhausting to keep track of. With a long, colorful history of failed predictions, it occurred to almost everyone at once that very little of what we imagined our own futures to be would really happen. So why bother?

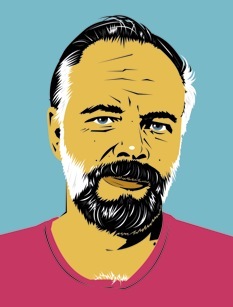

A few science fiction authors seemed to given up on the future. Neal Stephenson now writes historical fiction, and William Gibson set his latest book (Spook Country) in the present. He says the current times are much weirder than he could ever make up. The late Philip K. Dick, legendary outsider science fiction author, is currently Hollywood’s fountainhead, inspiring one feature film after another (Blade Runner, Total Recall, Minority Report, Scanner Darkly). Dick has a post-future view that is explored in a recent, fantastic profile in the New Yorker. Here’s the pertinent bit:

Although “Blade Runner,” with its rainy, ruined Los Angeles, got Dick’s antic tone wrong, making it too noirish and romantic, it got the central idea right: the future will be like the past, in the sense that, no matter how amazing or technologically advanced a society becomes, the basic human rhythm of petty malevolence, sordid moneygrubbing, and official violence, illuminated by occasional bursts of loyalty or desire or tenderness, will go on. Dick’s future worlds are rarely evil and oppressive, exactly; they are banal and a little sordid, run by a demoralized élite at the expense of a deluded population. No matter how mad life gets, it will first of all be life.

And this:

In “Ubik” (1969), in turn, the first premise is that the ancient human dream of communication with the dead has been achieved at last-but, when you go to speak with them, there is static and missed connections and interference, and then you argue over your bill. ….

The typical Dick novel is at once fantastically original in its ideas and dutifully realistic in charting their consequences. No matter what things may come, they will be exploited, merchandised, and routinized by the force of human weakness. And the interesting corollary: it won’t matter; the world of speaking ghosts will work about as well as this one. A society of paranoids can work as well as Nixon’s America did and, perhaps, in similar ways.

As Yogi Berra should have said, It’s possible that in the future, no one will go there anymore.