A Web Page For Every Species

Here’s a story about something big. Big as the planet. Not well known, but important. I go into great detail because I was present for part of its rise. It’s also the story of how big things get done. With set-backs, failures, many people, unexpected turns. This is not the whole story; it is just beginning. There may be lessons for others hoping to launch a big hairy audacious idea.

It all started at a dinner at the February 2000 TED hosted by Nathan Myrvold. At the height of the dotcom boom one of the dinner guests (not Nathan) was lamenting the difficulty of giving away a billion dollars. He was serious. To do it right — to spend it smartly, effectively — meant building some kind of large apparatus, usually a foundation, which burned a lot of the money. The more ambitious your goals, the more the organization would self-consume the billion dollars. But if you didn’t have a guiding principle for something grand, you’d fritter away the billion dollar opportunity to make a mark. What would be a bold, high-leverage thing to do with a billion dollars he asked?

I had never thought about it before (a billion dollars was not my problem), but sometime later that evening I had a flash. “I know what to do with a billion dollars, ” I said. “Use it to pay local people around the world to catalog the planet’s biodiversity in their neighborhood. This is a grand project that would yield vital, essential, and enabling knowledge, help the planet, and it would put the billion dollars into the hands of people who could really use it, not for charity, but for work they did.”

Nobody paid any attention to my suggestion, and I forgot all about the idea myself. But a few days later, Stewart Brand, who as at the dinner, said, “You really should do that billion dollar project.” I replied, “What billion dollar project?” He said, the species catalog. It really needs to be done.

I was certain the idea was so obvious that surely biologists were already in the middle of doing it. After a few days of researching it was clear that there was no up-and-running program to catalog all species on earth. There were several programs to unify the unorganized knowledge of known species into one master list. The most outspoken proponent of this idea was legendary ant specialist and writer E. O. Wilson. In 2000 he was calling for a “global biodiversity map” to cure for our deep ignorance of life on Earth.

In the realm of physical measurement, evolutionary biology is far behind the rest of the natural sciences. Certain numbers are crucial to our ordinary understanding of the universe. What is the mean diameter of the earth? It is 12,742 kilometers (7,913 miles). How many stars are there in the Milky Way, an ordinary spiral galaxy? Approximately 1011, 100 billion. How many genes are there in a small virus? There are 10 (in øX174 phage). What is the mass of an electron? It is 9.1 x 10^-28 grams. And how many species of organisms are there on Earth? We don’t know, not even to the nearest order of magnitude.

Ed Wilson with one of his ant collections, personally mounted and tagged.

One thing led to another, so Stewart, Ryan Phelan (DNA Direct) and I decided to host a meeting of taxonomists (the catalogers and conservers of species) to see if a dedicated campaign to catalog all the species on earth in 25 years was a possibility. Ed Wilson joined our board, along with a few other notable conservation biologists and taxonomists. The upshot of the meeting was that it turned out we knew less than I thought we knew. Estimates of the percentage of unknown species varied from 70% to 99%. It was clear we did not even know how many species we already “knew” with any precision. We roughly had identified 1 million plus organisms out a possible 7 to 200 million species on earth. We ended the meeting with the idea that all this “unclaimed” dotcom money might be a great opportunity to finish the task the Swedish naturalist Linnaeus began 300 years earlier.

I wrote out a manifesto for this endeavor called the All Species Inventory and published it in the Fall 2000 issue of Whole Earth Review. It recounts the reasons why I believe the world needs an inventory of life on earth. You can read it, but it begins:

If we discovered life on another planet, the first thing we would do is conduct a systematic inventory of that planet’s life. This is something we have never done on our home planet. The aim of the All Species Inventory is simple: within the span of our own generation, record and genetically sample every living species of life on Earth.

My main contribution was upping the ante. No one in the biological community had dared suggest we should aim for ALL species (they knew too much). And imagining we could do ALL in one generation seemed insane. It had taken hundreds of years to complete only one million.

While outlining the reasons to why doing ALL was important I realized I was an “all-ist.” A person who believes there is a transformation phase transition when you go from many, most, to all. From the manifesto:

“All” is the crucial term. The difference between “many” and “all” is the difference between, say, a local public library and the universal library of all documents and texts. Knowledge crosses a threshold when it goes from “most” to “all.” Geography crossed the threshold when it went from knowing a lot of the world to creating a globe with all continents in rough form; anatomy crossed the threshold once it produced a diagram of all the bones, all tissues, and all organs in a human body.

“Imagine doing chemistry knowing only one third of the periodic table,” says biologist Terry Gosliner. Sure, it can be done, but with an immense handicap. We are trying to do biology knowing perhaps only a tenth, or one hundredth, of our species. It is an immense handicap that does not need to exist.

One of the biologists attending the first meeting had come into some family stock which was flying high at the peak of the dotcom craziness and he wanted to cash it out to fund this risky biological adventure. So Ev Schlinger, a world expert on fly and fly parasites, funded the All Species Foundation with a million dollars. Our aim was to use new technology to accelerate the rate of species discovery from thousands of new species per year to millions per year.

While identifying all undiscovered species is the grand scheme, E.O. Wilson has always personally championed a smaller — but still huge — first step: to collect all the discovered species into a universally accessible format. I suggested that what we really wanted was a web page for every species. We could even generate a blank page for each named species and let any enthusiast fill them up. This notion was pretty radical in 2000, since there was no Wikipedia to prove the idea, and taxonomy is much harder than editing an article. Even worse, unauthorized information is a no-no in taxonomy.

On one flight across the US I sat next to Ed Wilson. Ed writes about a book per year. In long hand. On yellow lined paper pads. His trusty assistant does his email for him. Here is a snapshot of his latest book — a novel! — as he works on it.

Ed thinks in terms of books. He wrote up a new manifesto: a call for an Encyclopedia of Life.

Imagine an electronic page for each species of organism on Earth, available everywhere by single access on command. The page contains the scientific name of the species, a pictorial or genomic presentation of the primary type specimen on which its name is based, and a summary of its diagnostic traits.

At All Species we eventually made a universal search engine which scoured all known species lists and returned a “page” for every species, but we soon ran out of money. The dot-bust was now in progress and after a few more interesting but minor projects, but no additional funding, the foundation ceased.

However the taxonomists on our boards did not give up. In 2004, they gathered with others in Telluride, CO and hammered out a procedure to make an Encyclopedia of Life. They continued to develop an open-source protocol for electronically communicating species information (GBIF). They developed incredibly cool ways to digitally construct a photograph of a biological specimen so that the composited photo had more information in it than the specimen under a microscope.

Take a look at this image of a ant, which is an aggregated mosaic of dozens of digital photos taken in focus at different layers to give one full-dept in-focus image — a picture which a microscope or your eye won’t give up. This new tool enables inspection taxonomists to inspect key specimens remotely instead of having to ship fragile specimens around the world, and this tool lets more than one researcher at a time inspect this key specimen. The taxonomists developed methods of mass-processing specimens from tropical areas, greatly speeding up discovery. And genetics came in force. Maverick upstart Craig Venter proved that you could genetically sample air, soil and water and identify new genes of news species at the rate of thousands per day. It was a whole new world.

The dream of identifying all the species on earth in 25 years no longer seemed insane.

Completing a circle, at the 2007 TED, seven years after that dinner, Ed Wilson won the TED Wish. His wish was to have the TED attendees and the public at large help him produce the first real Encyclopedia of Life. He wrote a letter to the MacArthur Foundation, who responding with the first funding for this project. Recently, the taxonomists who never gave up on the idea of All Species, like Terry Erwin, Christian Samper, Peter Raven, to name a few close to us, created a broad consortium of university and natural history museums to fund and curate the Encyclopedia of Life, with a web page for every species.

Last month, at February 2008 TED, eight years later, the consortium launched the Encyclopedia of Life (EOL). Ed’s wish (and mine) fulfilled so to speak. The first 30,000 species got their active web pages. Another 1 million species got blank pages, with only their names filled in. In other words, the EOL is still mostly blank — but real.

The EOL is handsome, intelligently designed, and ambitious. When you query it, you get a photo (if available) of the organism, its species classification chart, a basic legal description, some ecological information – where found, etc. This information is primarily pulled from existing taxonomic databases such as FishBase, AmphibiaWeb, and AntWeb, and translated into a common interface. Some of the info comes from Wikipedia.

Turns out that while we were waiting, Wikipedia has been serving as the EOL. If you want to know about a species, just type the latin or popular name into Wikipedia (not Wikispecies). Even though field biologists insist strongly, repeatedly, in no uncertain terms, that random authors can’t supply reliable scientific information, they can. Because they aren’t random authors. In any case the scientists at EOL have seen the light. They will be accepting taxonomically non-critical submissions from enthusiasts later this year; that is photos, sightings, observational notes, and so on. And they are working directly with Wikipedia to coordinate their efforts in tapping the commonwealth of eager contributors.

But as good as EOL will be, it is still only a small part of the original All Species vision. I believe, more than ever, that it is possible and essential to inventory all the living things on earth, in one generation. The reasons to do it before are still valid:

* Every species on earth is hacking the rules of life and has discovered unique methods, materials, processes, and genes for living that are, or could be, valuable to us. If we knew about them.

* We can’t do holistic biology, systematic ecology, or intelligent conservation knowing only a few percent of the ingredients. We have to start with all species.

* A global inventory can employ highly skilled naturalists in remote and familiar regions, bridging two worlds of knowledge, and distributing wealth to where it can do some good.

* We are morally obligated to know our fellow passengers, and understand their roles and positions while on this small planet together. The more we know the better we can love.

But how do we do it? In broad strokes the procedure for identifying new organisms today is roughly identical to the way it was done during Darwin’s day. It is hugely labor intensive, and bottle-necked by the few key experts in each taxonomic domain. Only those very few will know if it is a new species or not. The traditional method simply does not scale.

The solution is new technology. The most potent force in taxonomy is genetic sequencing, since every species has a unique gene pattern. What we all want is a nifty handheld tricorder that reads the genes and can tell you what species you are holding. For 99% of the specimens you will pick up, the tricorder’s EOL database will know what it is. In that step alone, 99% of the hard work in discovering new species is eliminated. Because most of the precious inspection time of the world’s expert in some taxon or another is spent is looking through huge piles of candidates that science already knows about. What we need is a system where smart devices linked to the EOL database go through all the known specimens and present to the world’s expert only the unknown and mystery specimens. Attaining that requisite level of knowledge in humans represents 10 years of deliberate practice, and is in short supply, but it can and will be done via computational genetics. At first the assay will be done in a lab, and then soon enough, it will happen in the trusty tricorder in the field.

When anyone can buy a hand held species identifier, and amazing transformation will take place: everyone will become a taxonomist. At first this sounds absolutely counter-intuitive, because one would think that if you have to rely on a machine to identify species, you will become less of a taxonomist than you would if you steeped yourself in natural history and spent years studying organisms close up. This is the same incorrect logic that many teachers used against bringing calculators into the classroom. The argument was: calculators would lessen mathematic ability. But in fact calculators can increase both higher math skills, and interest in math. Turns out that doing arithmetic in your head was the least important thing in mathematics. By offloading that easily tripped-up skill onto a machine, the higher skills were enabled.

We see a similar phenomenon happening in cartography and typography. Both of these were formerly esoteric practices. The number of folks who knew about fonts and kerning, or rubbersheeting and lat-long, numbered in the tens of thousands. But now that fonts are loaded into every PC, and kerning a matter of dragging your mouse, when Google maps are a click away, the rote work of type design and map making are done by machines empowering hundreds of millions of new enthusiasts in these fields.

The Species ID’er will do the same. It will accelerate a learning feedback loop in taxonomy that is now broken. If on one of your walks you find a new-to-you species, it is extremely difficult to get a trustworthy identification. It can take years just to learn how to use book-based keys, and very few amateurs will learn to use keys in more than one field. And many taxon groups still require an expert to sort out. So getting a confirmation of your own identification will either take hours, days, or months, if it happens at all.

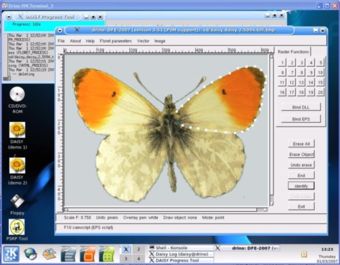

DAISY is software that can identify species of insects.

But when you have a handy Species ID’er, you try your best to identify something new to you. You’ll get instant feedback. Either, yes, you are correct! Good job! Or, nope, it is this species and here’s why. Or, very rarely, nope, we have no idea what it is. You may have discovered a brand new species! (At that point you bother the world’s expert who will be overjoyed to see you.)

I know from my own experience that anyone who can tell the difference between two types of lettuce can learn the differences in species — if you have a learning feedback. The instant feedback of a Species ID’er will educate millions of backyard taxonomists in record time. With the device in their backpack they will fan out from their own neighborhoods into the rest of the world, joining up with local naturalists to fill in the gaps in the EOL. With the enabling power of a taxonomic calculator, taxonomy will become a mainstream pursuit.

We can then move from doing a global inventory of all living species to global and local censuses of life. Mapping out where each species lives, in what numbers, in which associations, etc. Honest ecological work, that because of the lack of easy species ID today, must be done by overeducated grad students. Empowered by cheap devices, anyone passionate about nature can be a ecologist.

I don’t know when we’ll be able to buy one of this on Amazon, but genetic sequencing is improving at Moore’s rate or faster. It will be built upon a fully inhabited Encyclopedia of Life. An EOL that is populated with all the key information about each species. Over time the EOL will provide enhanced photos of each species, in each of its life stages, with virtual 3D dissections. It will contain a digital 3D model of the “archetype” specimen, and a scan of the original description. And detailed maps of its home territories, charts of it closest relations, and a graph of its ecological network.

Out of this will come a predictive ecology, sound conservation choices, and a new citizen-based engagement with taxonomic knowledge. Without a doubt these will increase our respect for the life on this planet.

The non-profit Ryan, Stewart and I founded to substantiate this big idea is gone, but it accomplished something important. It introduce to the public an idea that won’t go away: the immediate need and possibility for a global-scale inventory of life on earth. The launch of EOL means this secret dream of taxonomists and field biologists is now a shared common dream. It’s a destination that has been put on the map, and can no longer be ignored. I’m am happy to see the dream begin with a web page for every species.