China Is an Island

China is the question mark in the equation of the world. Its answers affect the destiny of everyone else on the planet. Which way will it head?

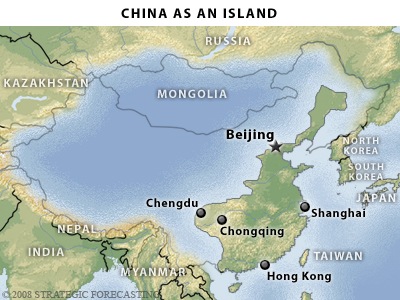

The picture below is the best single image I know of to explain the current riddle of China. It is taken from a monograph on the geopolitics of China posted by the military/corporate intelligence website Stratfor, summarized by pundit John Mauldin in his Outside the Box column, and pointed to by Strange Maps.

From Outside the Box:

Contemporary China is an island. Although it is not surrounded by water (which borders only its eastern flank), China is bordered by terrain that is difficult to traverse in virtually any direction. There are some areas that can be traversed, but to understand China we must begin by visualizing the mountains, jungles and wastelands that enclose it. This outer shell both contains and protects China.

China shares borders with more countries (14 in total) than any other country on earth. Very few of those borders have ever been very permeable to migration of culture, commerce and ideas because of mountains, deserts, swamps, and high altitudes. In many ways China has acted as an island for millennia. The very large zone of an impermeable buffer, and mountainous and unfarmable land is shown in this image as water.

What’s left is the island of China. This is the traditional center of China, of fertile river valley farming, and home to the Han people. It is also the zone of manufacturing today. It is where all of its giant, throbbing cities lie. The island alone is huge, still among the largest countries in the world.

Prosperity in China is found only on the island. Off the island, in the waters deep, China remains remarkably undeveloped. In fact the level of development in the “Chinese waters” is about equal to the low levels of the neighboring countries. I was surprised to find in my own travels that many towns in the Chinese waterland were as remote, poor, and disadvantaged as any places I had seen in Nepal, Burma, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Afghanistan — all neighbors of China. Not coincidentally, this waterland is also inhabited by non-Han peoples, what the Chinese call their minorities. It is not just Tibet where the nan-Han are outnumbered. In most of the counties covered by this buffer zone (shown as water), minorities dominate. There are lots of them, speaking their own language, often their own dress. What is most remarkable is how remote the rich island seems from the outer waterlands.

The China everyone talks about is the island. China’s worry is the outer zone will leave. Will they go the way of the Soviet Union and break off one by one? Will there be two futures? Much of the control-freak nature of the central political party has been trying — at almost all costs — to keep the whole waterland under control of the island — to keep the country intact. And when you look at this map, it is clear that a break up, or at least a break down, is a very real possibility. In fact the more you look at it, the more amazing it is that China has not devolved before now.

John Mauldin:

The first geopolitical imperative of China is to ensure the unity of Han China. The interior has remained extraordinarily poor. The coastal region [the island] is deeply enmeshed in the global economy. The interior is not. Beijing is once again balancing between the coast and the interior. Beijing’s interest is in maintaining internal stability. As pressures grow, it will seek to increase its control of the political and economic life of the coast. The interest of the interior is to have money transferred to it from the coast. The interest of the coast is to hold on to its money. Beijing will try to satisfy both, without letting China break apart and without resorting to Mao’s draconian measures. But the worse the international economic situation becomes the less demand there will be for Chinese products and the less room there will be for China to maneuver. The more effective it becomes at exporting, the more of a hostage it becomes to its customers. …The fact is that the rest of the world is far less dependent on China’s exports than China is dependent on the rest of the world.

The large underdeveloped, rugged, and minority geography represented by China’s waterlands continue to isolate China. This vast region acts as a military buffer, a cultural barrier, and a damper on economic improvement. Whether China can grow out of its island and spread, or whether it will have its waterlands removed, is a question that will influence its destiny as much as, or more than, the price of oil, or the actions of the rest of the world.