Steam-Engine-Time

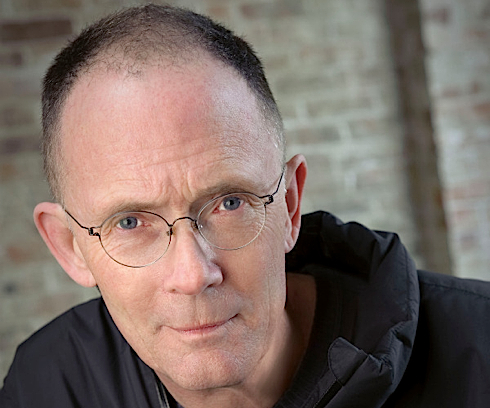

This long revealing interview with William Gibson is a gold mine. In addition to being a gifted writer, Gibson is one of the best conversationalists I’ve encountered. I could listen to him all day. (This interview in The Paris Review reminds me how great interviews can be when you allow them to meander and go deep and long. The way Rolling Stone, Playboy, Interview and even Wired (briefly) used to do.) Among other things Gibson tells the story of how he came up with the concept of cyberspace while writing his novel on a manual typewriter. He also explains why he writes in the present versus the future these days. [Image by Michael O’Shea]

A few excerpts:

*

If you’d gone to a publisher in 1981 with a proposal for a science-fiction novel that consisted of a really clear and simple description of the world today, they’d have read your proposal and said, Well, it’s impossible. This is ridiculous. This doesn’t even make any sense. Fossil fuels have been discovered to be destabilizing the planet’s climate, with possibly drastic consequences. There’s an epidemic, highly contagious, lethal sexual disease that destroys the human immune system, raging virtually uncontrolled throughout much of Africa. New York has been attacked by Islamist fundamentalists, who have destroyed the two tallest buildings in the city, and the United States in response has invaded Afghanistan and Iraq. By the time you were telling about the Internet, they’d be showing you the door. It’s just too much science fiction.

*

We’ve gotten so used to emergent technologies that we get anxious if we haven’t had one in a while.

*

I’ve always been taken aback by the assumption that my vision is fundamentally dystopian. I suspect that the people who say I’m dystopian must be living completely sheltered and fortunate lives. The world is filled with much nastier places than my inventions. If you’re living in most places in Africa, you’d jump on a plane to the Sprawl in two seconds. Many people in Rio have worse lives than the inhabitants of the Sprawl.

*

That wasn’t the way science fiction advertised itself. The self-advertisement was: Technology! The world of the future! Educational! Learn about science! It didn’t tell you that it would jack your kid into this weird malcontent urban literary universe and serve as the gateway drug to J. G. Ballard.

And nobody knew. The people at the high school didn’t know, your parents didn’t know. Nobody knew that I had discovered this window into all kinds of alien ways of thinking that wouldn’t have been at all acceptable to the people who ran that little world I lived in.

*

I was walking around Vancouver, and I remember walking past a video arcade, which was a new sort of business at that time, and seeing kids playing those old-fashioned console-style plywood video games. The games had a very primitive graphic representation of space and perspective. Some of them didn’t even have perspective but were yearning toward perspective and dimensionality. Even in this very primitive form, the kids who were playing them were so physically involved, it seemed to me that what they wanted was to be inside the games, within the notional space of the machine. The real world had disappeared for them–it had completely lost its importance. They were in that notional space, and the machine in front of them was the brave new world.

The only computers I’d ever seen in those days were things the size of the side of a barn. And then one day, I walked by a bus stop and there was an Apple poster. The poster was a photograph of a businessman’s jacketed, neatly cuffed arm holding a life-size representation of a real-life computer that was not much bigger than a laptop is today. Everyone is going to have one of these, I thought, and everyone is going to want to live inside them. And somehow I knew that the notional space behind all of the computer screens would be one single universe.

*

There’s an idea in the science-fiction community called steam-engine time, which is what people call it when suddenly twenty or thirty different writers produce stories about the same idea. It’s called steam-engine time Âbecause nobody knows why the steam engine happened when it did. Ptolemy demonstrated the mechanics of the steam engine, and there was nothing technically stopping the Romans from building big steam engines. They had little toy steam engines, and they had enough metalworking skill to build big steam tractors. It just never occurred to them to do it. When I came up with my cyberspace idea, I thought, I bet it’s steam-engine time for this one, because I can’t be the only person noticing these various things. And I wasn’t. I was just the first person who put it together in that particular way, and I had a logo for it, I had my neologism.

The actual phrase was first coined by the collector of weird, Charles Fort, in 1931, who wrote in his early fantasy novel Lo!: “A tree cannot find out, as it were, how to blossom, until comes blossom-time. A social growth cannot find out the use of steam engines, until comes steam-engine-time.”

Steam-engine-time is another name for technological determinism, which is another way to say simultaneous independent invention, Turns out simultaneous parallel discovery and invention are the norm in science and technology rather than the exception (see my previous post).

When it is steam-engine-time, steam engines will occur everywhere. But not before. Because all the precursor and supporting ideas and inventions need to be present. The Romans had the idea of steam engines, but not of strong iron to contain the pressure, nor valves to regulate it, nor the cheap fuel to power it. No idea – even steam engines — are solitary. A new idea rests on a web of related previous ideas. When all the precursor ideas to cyberspace are knitted together, cyberspace erupts everywhere. When it is robot-car-time, robot cars will come. When it is steam-engine-time, you can’t stop steam engines.

Right now it is social-media-time.