Chosen, Inevitable, and Contingent

[Translations: Japanese]

In 1964 I visited the New York World’s Fair as a wide-eye, slack-jawed kid. The inevitable future was on display and I swallowed it up in great gulps. At the AT&T pavilion they had a working picture phone. The idea of a video-phone had been circulating in science fiction for a hundred years earlier in a clear case of prophetic foreshadowing. Now here was one that actually worked. Although I could see it, I didn’t get to use it then, but photos of how it would infuse our suburban lives ran in the pages of Popular Science and other magazines. We all expected it to appear in our lives any day. Well, the other day, 45 years later, I was using a picture phone just like the one predicted way back in 1964. As my wife and I gathered in our California den to lean toward a curved white screen displaying the moving image of our daughter in Shanghai we mirrored the old magazine’s illustration of a family crowded around a picture phone. While our daughter watched us on her screen in China, we chatted leisurely about unimportant family matters. Our picture phone was exactly what everyone imagined it to be, except in three significant ways: the device was not exactly a phone, it was our iMac and her laptop; the call was free (via Skype, not AT&T); and despite being perfectly useable, and free, picture-phoning has not become common — even for us. So unlike the earlier futuristic vision, the inevitable picture phone has not become the standard modern way of communicating.

So was the picture phone inevitable? There are two senses of “inevitable” when used with technology. In the first case, an invention merely has to exist once. In that sense, every technology is inevitable because sooner or later some mad tinkerer will cobble together almost anything that can be cobbled together. Jetpacks, underwater homes, glow-in-the-dark cats, forgetting pills — in the goodness of time every invention will inevitably be conjured up as a prototype or demo. And since simultaneous invention is the rule not the exception, any invention that can be invented will be invented more than once. But few will be widely adopted. Most won’t work very well. Or more commonly they will work but be unwanted. So in this trivial sense, all technology is inevitable. Rewind the tape of time and it will be re-invented.

The second more substantial sense of “inevitable” demands a level of common acceptance and viability. A technology’s use must come to dominate the technium or at least its corner of the technosphere. But more than ubiquity, the inevitable must contain a large-scale momentum, and proceed on its own determination beyond the free choices of several billion humans. It can’t be diverted by mere social whims.

The picture phone was imagined in sufficient detail a number of times, in different eras and different economic regimes. It really wanted to happen. One artist sketched out a fantasy of it in 1878, only two years after the telephone was patented. A series of working prototypes were demoed by the German post office in 1938. Commercial versions were installed in phone booths in New York City after the 1964 World’s Fair, but AT&T canceled the product ten years later due to lack of interest. At its peak the Picturephone had only 500 or so paid subscribers, even though nearly everyone in New York recognized the vision. One could argue that rather than being inevitable progress, this was an invention battling its own inevitable bypass.

Yet today, it is back. Perhaps it is more inevitable over a 50-year span. Maybe it was too early back then, and the necessary supporting technology absent and social dynamics not ripe. In this respect the repeated earlier tries can be taken as evidence of its inevitability, its relentless urge to be born. And perhaps it is still being born. There may be other innovations yet to be invented that could make the videophone more common. Such needed innovations as: ways to direct the gaze of the speaker into your eyes instead of towards the off-center camera, or have the screen switch gazes among multiple parties in the conversation.

We can see both arguments for the picture phone: a) that it had to happen, or b) that it did not have to happen, and it still may not really happen beyond the minor, occasional use on Skype. So does any technology lurch forward on its own inertia as “a self-propelling, self-sustaining, ineluctable flow”, in the words of technology critic Langdon Winner, or do we have clear free-will choice in the sequence of technological change, a stance that makes us (individually or corporately) responsible for each step?

I’d like to suggest an analogy:

Who you are is determined in part by your genes. Every single day scientists identify new genes that code for a particular trait in humans, revealing the ways in which inherited “software” drives your body and brain. We now know that behaviors such as addictions, ambition, risk-taking, shyness and many others have strong genetic components. At the same time, “who you are” is clearly determined by your environment and upbringing. Every day science uncovers more evidence of the ways in which our family, peers, and cultural background shape our being. The strength of what others believe about us is enormous. And more recently we have increasing proof that environmental factors can influence genes, so that these two factors are co-factors in the strongest sense of the word — they determine each other. Your environment (like what you eat) can affect your genetic code, and your code will steer you into certain environments — making untangling the two influences a conundrum.

Lastly, who you are in the richest sense of the word — your character, your spirit, what you do with your life — is determined by what you choose. An awful lot of the shape of your life is given to you and is beyond your control, but your freedom to choose within those givens is huge and significant. The course of your life within the constraints of your genes and environment is up to you. You decide whether to speak the truth at any trial, even if you have a genetic or familial propensity to lie. You decide whether or not to risk befriending a stranger, no matter your genetic or cultural bias. You decide beyond your inherent tendencies or conditioning. Your freedom is far from total. It is not your choice alone whether to be the fastest runner in the world (your genetics and upbringing play a large role) but you can choose to be faster than you have been. Your inheritance and education at home and school set the outer boundaries of how smart, or generous, or sneaky you can be, but you choose whether you will smarter, more generous and sneakier today than yesterday. You may inhabit a body and brain that wants to be lazy, or sloppy, or imaginative, but you choose to what degree those qualities progress (even if you aren’t inherently decisive).

Curiously, this freely chosen aspect of ourselves is what other people remember about us. How we handle life’s cascade of real choices within the larger cages of our birth and background is what makes us who we are. It is what people talk about when we are gone. Not the givens. But the choices we took.

It is the same with technology. The technium is in some part preordained by the inherent nature of technology itself. Just as our genes drive the inevitable unfolding of human development, starting from a fertilized egg, proceeding to an embryo, then fetus, to an infant, a toddler, kid, and teenager, so too the largest trends of technology unroll in developmental stages.

In our lives we have no choice about becoming teenagers. The strange hormones will flow, and our bodies and minds must morph. Civilizations follow a similar developmental pathway as well, although its outlines are less certain because we have witnessed a sample of one. But we can discern a necessary ordering: a society must control fire first, then metalworking before electricity, and electricity before global communications. We might disagree on what exactly is sequenced, but a sequence there is.

At the same time, history matters. Technological systems gain their own momentum, and become so complex and self-aggregating that they form an environment for other technologies. The infrastructure built to support the gasoline automobile is so extensive that over a century of expansion it now affects technologies outside of transportation. For instance, the invention of air-conditioning plus the highway system encouraged sub-tropical suburbs. The invention of cheap refrigerated air altered the landscape of the American south and southwest. If air-conditioning had been implemented in a non-auto society, its pattern of consequences would be different even though air cooling systems contain their own technological momentum and inherencies. So every new development in the technium is contingent upon the historical antecedents of previous technologies. In biology this effect is called co-evolution, and it means that the “environment” for one species is the ecosystem of all the other species it interacts with, all of them in flux. For example prey and predator evolve each other in a never-ending arms race, host and parasite become one duet as they try to outbest each other, and an ecosystem will adapt to the moving target of a new species adapting to it.

Within the borders laid out by inevitable forces, our choices unleash consequences that gain momentum over time until these contingencies harden into technological necessities and become nearly unchangeable in future generations. There’s an old story that is basically true: Ordinary Roman carts were constructed to match the width of Imperial Roman war chariots because it was easier to follow the ruts in the road left by the war chariots. The chariots were sized to accommodate the width of two large war horses, which translates into our English measurement as a width of 4′ 8.5″. Roads throughout the vast Roman empire were built to this spec. When the legions of Rome marched into Britain, they constructed long distance imperial roads 4′ 8.5″ wide. When the English started building tramways, they used the same width so the same horse carriages could be used. And when they started building railways with horseless carriages, naturally the rails were 4′ 8.5″ wide. Imported laborers from the British Isles built the first railways in the Americas using the same tools and jigs they were used to. Fast forward to the US Space shuttle, which is built in parts around the country and assembled in Florida. Because the two large solid fuel rocket engines on the side of the launch Shuttle were sent by railroad from Utah, and that line transversed a tunnel not much wider than the standard track, the rockets themselves could not be much wider than 4′ 8.5.” As one wag concluded: “So, a major Space Shuttle design feature of what is arguably the world’s most advanced transportation system was determined over two thousand years ago by the width of two horses’ arse.” More or less, this is how technology constrains itself over time.

The past 10,000 years of human technology will sway the preordained march of technology in each new era. The initial conditions of an electrical system, for example, can guide it in several ways. The technical specifications could default to either AC or DC, favoring centralization (AC) or decentralization (DC). Or it could be installed in 12 volts (by amateurs) or 250 volts (by professionals). The legal regime could favor patent protection or not, and the business models could be built around profits or nonprofit. All these variables would bend the unrolling system in different cultural directions. Yet electrification in some form was a necessary, unavoidable phase for the technium. These initial specifications later affected how the internet developed on top of the electric network. The internet, too, was inevitable, but the character of its incarnation is contingent on the tenor of the technologies that preceded it. Telephones were inevitable, but the iPhone isn’t. We accept the biological analog: human adolescence is inevitable, but pimples are not. The exact pattern that the inevitable teenagehood manifests in any individual will depend in part on his/her biology, which depends in part of their past health and environment.

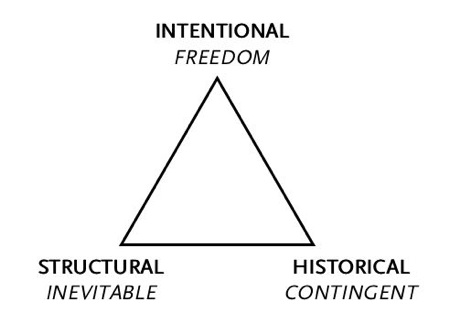

As in personality, technology is shaped by a triad. In addition to the primary drive of preordained development (force #1), and in addition to the escapable influences of technological history (force #2), there is society’s collective free will in shaping the technium (force #3). Under the first force of inevitability, the path of technological evolution is steered by both the laws of physics, and by self-organizing biases within its large complex adaptive system. The technium will tend toward certain macro forms, even if you rerun the tape of time. The path of the technium is further constrained by the second force created by the momentum of past decisions, or technological history. At any moment of technological conception what happens next is contingent of what has already happened, and so history constrains our choices forward. These two forces channel the technium along a limited path, and severely restrict our choices. We like to think that “anything is possible next” but in fact anything is not possible in technology.

In contrast to these two, the third force is our free will to make individual choices of use, and collective policy decisions. Compared to all possibilities that we can imagine we have a very narrow range of choices. But compared to 10,000 years ago, or even 1,000 years ago, or even last year, our possibilities are expanding. Although restricted in the cosmic sense, we have more choice than we know what to do with. And via the engine of the technium, these real choices will keep expanding (even though the larger path is preordained).

This paradox is experienced not just by historians of technology but ordinary historians as well. In their view “human freedom actually exists within the limits set by the historical process. While not everything is possible, there is much that can still be chosen.” And so as historian David Apter writes, “to be modern means to see life as alternatives, preferences and choices” in “a process of increasing complexity in human affairs within which the polity must act,” that is within a course that is determined. Historian of technology Langdon Winner sums up this convergence of free will and the ordained, which the historian of technology Jacques Ellul also held, in these terms: “technology moves steadily onward as if by cause and effect. This does not deny human creativity, intelligence, idiosyncrasy, chance, or the willful desire to head in one direction rather than another. All of these are absorbed into the process and become moments in the progressions.”

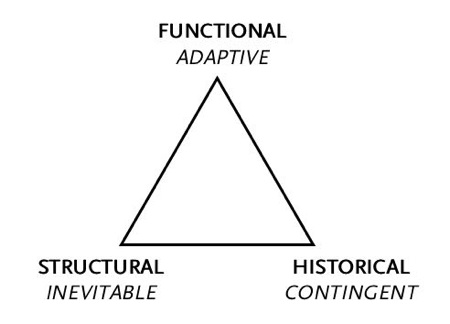

The triadic nature of the technium is reflected by the triadic nature of biological evolution — which makes sense since the technium is the acceleration of evolution. (This representation is roughly based on Steven Jay Gould’s analysis, as described in my Ordained Becoming.) The basic laws of physics and emergent self-organization drive evolution towards certain forms of life. Specific species are unpredictable in their micro details, but the macro patterns of bilateral symmetry, or streamlined bodies underwater, or eyeballs are ordained by the physics of matter and self-organization. This inescapable force can be thought of as the structural inevitability of evolution.

The second aspect of evolution’s triad is the historical aspect of biological change. Earlier accidental mutations and circumstantial opportunities bend the course of evolution this way and that — contingency within the bounds of inevitable. Lastly, the third force working within evolution can be thought of as the adaptive function — the relentless engine of optimization and creative innovation that continually solve the problems of survival. All three work together to propel evolution through a channel of a finite number of basic forms, but with unexpected and novel variation.

The triad nature of technology is very similar. But instead of an unconscious adaptive function, the technium possess a conscious adaptive function of human ingenuity and free will. In biological evolution there is no designer, but in the technium there is an intelligent designer — Sapiens. The other two legs of technological evolution are identical. The basic laws of physics and emergent self-organization drive technological evolution through an inevitable series of structural forms — wheels, steam engines, binary software, etc. At the same time, the historical contingency of past inventions forms an inertia which bends evolution this way or that — with the bounds of the inevitable developments. Lastly, the collective choice of free-willed individuals select the character of the technium. And just as our free-will choices in our individual lives create the kind of person we are (our ineffable “person”), so too in the technium.

Winner gives an example of how this conundrum of choice within the ordained can be visualized. He says, the “Lapps of the Sevettijarvi region deliberately chose to use snowmobiles as a replacement for dogsleds and skis in the basis of their economy–reindeer herding. But they neither chose nor intended the effect this change would have in totally reshaping the ecological and social relationships upon which their traditional culture depended.” Those larger consequences are driven by the larger trajectory of the technium.

We may not be able to choose the macro scale outlines of an industrial automation system — say assembly line factories, fossil fuel power, mass education, allegiance to the clock — but we can choose the character of those parts. We have latitude in selecting the defaults of our mass education, so that we can nudge the system to maximize equality, or to favor excellence, or to foster innovation. We can bias the assembly line either towards productivity of output or productivity of worker skills. Every technological system can be set with alternative defaults that will change the character and personality of that technology.

So the natural question is, if certain aspects of the technium are preordained by the laws of physics and natural self-organization, and certain aspects contingent upon our choices now and in the past, how do we know which is which? Systems theorist John Smart, who also describes the technium in terms of a triad (though different than the one presented here) suggests that we need a technological version of the Serenity Prayer. Popular among participants in twelve-step addiction recovery programs, the Prayer, originally written in the 1930s by the theologian Rheinhold Niebuhr, goes:

God grant me the serenity

To accept the things I cannot change;

Courage to change the things I can;

And wisdom to know the difference.

Where is the source for the wisdom to discern the difference between the inevitable stages of technological development and the volitional forms that are up to us? What we would really like is a technique which makes the inevitable obvious.

I think that tool is our awareness of the technium’s long-term cosmic trajectory. By placing technology in the context of a natural extension of biological evolution rising from the big bang, we can perceive how those macro imperatives play out in our present time. In other words, technology’s inevitable forms derive from the dynamics that characterize all extropic systems — the dozen or so attributes I describe as “what technology wants.” These are: an increase in complexity, diversity, specialization, efficiency, consilience, socialization, structure, ubiquity, opportunity, beauty, sentience, and evolvability. All these values are increasing on average in sustainable systems like life, evolution, and the technium.

My hypothesis claims that as more of these long-term trends operate in a particular current technology, the more that technology will be characterized by “inevitable” forces. Indeed, it is these long term constraints which give an opening to the inevitable. I propose that whether a technology in question exhibits a tendency towards increased socialization, say, or moves toward consilience, or whether it increases or decreases volition and freewill, or diminishes or raises opportunities as it propagates, will, in aggregate signal its inevitability. An alignment with these extropic forces becomes the Serenity Prayer Filter. The more an idea moves along the frontier of those dozen qualities, the more inevitable that technology is for that time period.

Let me just give one small example of many. At this particular phase in the technium (at the turn of the 21st century), we are building many intricate, complex systems of communications. This wiring up of the planet can happen in a number of ways, but my modest prediction is that the technological arrangements that will be most sustainable in the long run — which I take as a by product of inevitability since the alternative arrangements drop away — will be those technologies that tend toward the greatest increases in diversity, consilience, opportunity, sociability, sentience, etc. We can compare two competing technologies to see which one favors more of these extropic qualities. Does it open up diversity or close it down? Does it bank on increasing opportunities or assume they wither? Is it moving towards embedded sentience, or ignoring it? Does it blossom in ubiquity, or collapse under it?

For example is large-scale petro-fuel-fed agriculture inevitable? This highly mechanical system of tractors, fertilizers, breeders, seed producers, and food processors provides the abundant cheap food which is the foundation of our leisure to invent other things, our longevity to keep inventing, and ultimately the increase in population that generates increasing numbers of new ideas. Compared to the food production schemes that preceded it — both subsistence farming, and animal-powered mixed farming at its peak — mechanicized farming was inevitable in that it increased energy efficiency, complexity, opportunities, structure, sentience and specialization.

However, because technological phases are developmental, they are eventually outgrown in the same way our infancy is outgrown. As in most growth, the earlier form is not discarded but subsumed. Our infant organs are not eliminated but are matured. In evolution, earlier structures are rarely extinguished. Usually they are built around by the new. Our own brains are the best evidence of this. We still retain an inner “reptilian” core that generates all the essential instincts that benefited our crawling primitive ancestors. When we are frightened the ancient “fight or flight” circuits are ignited. They have not disappeared. As our brains developed we added layers of cognition OVER the earlier still operating brain. That’s one reason our behavior is so complex. Later on in our evolutionary journey, we acquired mental patterns for social interactions that we share with other social primates, which govern much of our behavior and thinking. Our human consciousness is a very thin layer on top.

Our layers of technological acquisition reflects a similar subsumption pattern. The current “new economy” of information and communication is a thin layer that resides upon a very hearty industrial economy that is not going away. Just as subsistence farming is still the norm for most of the living farmers alive today (most of them living in the developing world), industrial farming will remain the largest producer of food for many decades, just as industrial processes continue to undergird the digital economy.

But just as a more intangible, more diverse, more sentient technology economy has appeared as a thin alternative layer upon the industrial world, so too, can we see hints of an alternative method of food production that is more in line with extropic principles. According to many food experts, the problems with the current food production system is that it is heavily dependent on monocultures (not diverse) of too few staple crops (five worldwide), which in turn require pathological degrees of interventions with drugs, pesticides, herbicides, soil disturbances and (reduced opportunities), and over reliance on cheap petro fuels for both energy and nutrients (misplaced energy efficiency). Alternative scenarios that can scale up to the global level are hard to imagine, but there are hints that a decentralized agriculture, with less reliance on politically motivated government subsidies, or petroleum, or on monocultures, would work. This evolved system of hyperlocal, hybrid farms might be manned by either a truly globally mobile migrant labor force (until pay differentials evened out), or with smart, nimble worker robots. In other words instead of highly technological mass production farms, highly technological personal or local farms. Compared then to the industrial factory farm as found in say the corn belt of Iowa, this type of advanced gardening would lean towards more diversity, more opportunities, more complexity, more structure, more specialization, more sentience, and would therefore more likely to be inevitable, after, or on top of the dominant industrial form of farming now.

We can ask the same questions for other technologies on the horizon. In this same field, are genetically modified foods inevitable? In the near future will they become the dominate type of crop planted and eaten world wide? My answer would be: probably. While many people will chose not to patronize genetically modified foodstuffs (just as they choose not to watch TV, or get vaccinated) the push of extropy will move food production in this direction because it further increases diversity, complexity, structure, sentience, etc in the technium. In fact the only trends working against genetically modified food are nostalgia and misunderstanding. There is a misguided idea that GM food is more engineered, when of course ordinary crops are highly technological, having been deliberately “engineered” through breeding for millennia. But breeding is an inferior type of technology because it relies on randomness (less structure) — take two parents and see what random offspring you get. In fact, in an alternative world where scientific GM food had been invented first, the newer invention of “natural” random breeding would be rejected as insanely crazy and dangerous. It is, as Danny Hillis calls it, “genetic gambling.” Why would you trust your food to chance?

We might apply these same heuristics to this sample list of controversial near-term or already prototyped inventions. Can we determine which, if any of these, is inevitable in the next 50 years?

Assisted-suicide devices

Human cloning

Memory pills

Underground CO2 sequestering

Brain-wave phone controllers

Public location trackers

Transcontinental maglev trains

Male contraception

Iris/face ID detectors

Free full genome sequence

Robot-driven cars

I don’t think we can in useful detail. The above innovations are too specific to forecast with any believability. But I do think we can discern the wider currents of change that carry them. We can describe the predetermined, long-term, macro elements of progress that flow through the technium and channel unpredictable details. That larger predictable framework can guide our policy and personal decisions. As an illustration I’ve taken the above list and suggested the trajectories I see in them:

Assisted-suicide devices — The technology is already here; we could make some amazingly clever contraptions if we wanted to, but the deployment of advanced killing devices is a choice, and not at all inevitable. However what is inevitable is the expansion of personal choice, the increase in specialized tools, the increase in smarter, more responsive machines that can tailor its actions to the most subtle signals of pain and consciousness, so technology will continue to move in the direction of making assisted suicide more attractive.

Human cloning — We have human clones now. They’re called twins. Whether we will intentionally create them on demand, and whether we’ll time shift their arrival so that they resemble serial twins, is a choice. While we choose, the drift of the technium will encourage all the technologies which make it easy to clone a human, in particular robust technologies that can clone all other animals. The power to clone a human will inevitably increase, but we may chose not to deploy it any more than suicide.

Memory pills — Pills are inevitable, and so are pills that enhance cognition. But the particulars of what we are able to enhance, or what to enhance, or choose to enhance, and under which conditions, seem open. Memory pills may not work, or the side effects may be debilitating. However, the extropic drive of the technium pushes toward maximizing mindedness, optimizing options, increasing specialization and socialization, accelerating our own evolution and all those trends lean towards more kinds of biochemical agents for our minds. There will be more smart pills, but we’ll have a strong choice in what kind.

Underground CO2 sequestering — The technium is inevitably moving towards global interaction, global awareness, and global action, and the global problem of greenhouse gases will need a global solution. Some kind of geo-engineering is inevitable, but the particular technique is not.

Brain-wave phone controllers — After keyboards, after voice command, there is thought command. Think of who you want to speak to and bingo you are connected. Or think of where you want to go, and your automobile takes you there. The usual biases propelling disembodiment, more complex structure, heightened sentience, and new sensory dimensions all make thought control inevitable, but whether we choose to use it everyday on phones is not. The technology will thrive in some domain; we have a choice in how and where we apply it.

Public location trackers — Location tracking technology will be built into every electronic gadget and article. Literally anything can be tracked anytime anywhere. It is up to us how. There are many ways this inevitable superpower can be dispensed.

Transcontinental maglev trains — There is nothing inevitable about long-distance maglev trains. Or any kind of specific long-distance transportation. Other than that we’ll have lots of it. And more of it, used more often. The inevitable trend is more miles traveled per person, even with, or despite the increase in communication bandwidth and fidelity. Increasing choice and freedom demand ever more mobility.

Male contraception — It will inevitably be an option, but it is totally evitable whether it becomes common.

Iris/face ID detectors — The irreversible slide towards greater socialization, more shared sentience, greater social structure, and integrated globalism means that some kind of biometric identification is inevitable. But we have a great degree of freedom in setting up the defaults and assumptions of this technology, and directing the shape of a society relying on this inevitable system.

Free, full genome sequences — Both the price and the data will be inevitable, but not who funds it, or whether it becomes mandatory, or public, or actionable.

Robot-driven cars — Inevitable, and sooner than you think. In a neat reversal many highways will be quick to ban human drivers because their driving will be proven to be less safe. Other regions will pride themselves on robot-free lanes. The arrangements of smart-machine/human will play out in a thousand different styles, all chosen.

Unless I am uncommonly lucky more than one of these speculations will be dead wrong. I don’t intend these tweets as predictions. They are meant to illustrate the triad nature of the technium, how the “self-propelling, self-sustaining, ineluctable flow” of technological forces pushes us along, swayed by the character of past inventions, but providing us plenty of room to choose the specific manner by which these forces are rendered. We choose whether to use our eyeballs as ID, or whether we share lanes with robot cars. But we don’t have a choice in whether cars become more robotic in general, or whether biometric IDs become more common, or whether we’ll have a global internet.

“Inevitable” is a fighting word. It raises hackles among many who doubt it exists in history. It also is seen by others as an excuse. The French philosopher of technology Jacques Ellul says “the process of technological advance surges along an ineluctable path largely because human agents have abdicated their essential role.” In other words, technologies are only inevitable if we let them be.

Inevitability is impossible to prove, particularly when we cannot rewind the tape of time, and particularly when we have a sample size of one. But we should not take inevitability as a loss or defeat. Inevitability makes prediction easier. The better we can forecast, the better prepared we can be for what comes. If we can discern the large outlines of persistent forces, we can better education our children in the appropriate skills and literacies need for thriving in that world. We can shift the defaults in our laws and public institutions to reflect that coming reality. If, for instance, everyone’s full DNA will be sequenced, then instructing everyone in genetic literacy becomes essential. Each must know the limits to what can, and cannot, be gleaned from this code, how it varies or not among related individuals, what might impact its integrity, what info about it can be shared, what concepts such as “race” and “ethnicity” mean in context, and how to use this knowledge to get therapeutics tailored to it. There’s a whole world to open up, and it will take time, but we can begin to sort these choices out now because its arrival, in alignment with the extropic principles, is pretty inevitable.

As the technium progresses, better tools for forecasting and prediction serve as our Serenity Prayer, helping us spot the inevitable outside the expanding universe of free choices that new innovations bring. To return to the adolescence analogy, because we can anticipate the inevitable onset of human adolescence, we are better able to thrive in it. Teenagers are biologically compelled to take risks as a means of establishing their independence. Evolution “wants” risky teenagers. Because risky behavior is expected in adolescence, this knowledge is both reassuring to teenagers (you are normal, not a freak) and to society, and an invitation employ that “normal” riskiness for improvement and gain. If we ascertain that a global web of continuous connection is an inevitable phase in a growing civilization, than we can be both reassured by this inevitability and take it as an invitation to make the best possible global web we can.

As technology advances we gain both more possibilities and, if we are smart and wise, better ways to anticipate choice-less trends. Our real choices in technology matter. Although constrained by inevitable forms of development, the particular specifics of a technological phase matter to us greatly. The chosen materialization of each technology supplies the character to our society. Electromagnetic radiation as a communication matrix was inevitable. But the particular social forms we used to invent radio make a huge difference to us. A simple choice such as whether the radio spectrum is shared or hoarded will shape the contours of its preordained appearance.

The lessons of the technium’s triad are this: 1) Anticipate the technium’s inevitable macro developments, and build better tools to predict them; 2) Make choices in technology that further the extropic principles of increasing opportunities, socialization, consilience, sentience, and so on. 3) Choose details and defaults with the awareness that our choices today form the constraints of tomorrow.

Easier said then done.