Election Prediction Markets

The Iowa Electronic Markets (IEM) trades real money in bets on future cultural events. Prediction markets sell contracts for an easily decidable future event (someone wins an election, a commodity hits a certain price, a movie sells X number of tickets). If that contract comes true, the different between what the price of the contract was when bought and its full price will be pocketed by the winner. So if $1 contracts for Bill Clinton winning the election were selling for 35 cents when you bought them, you would have profited 75 cents after the election.

Outside of the IEM most US predictions markets trade with token money to escape uncertain gambling and investor laws, which may prohibit real money trades. But in all prediction markets the price of a contract is decided by the collective demand, or in other words, by the collective mind. Outcomes with low expectations earn a low price. If you are a contrarian you can buy low value, low-expectation contracts, and if conventional wisdom is wrong (at that time), you’ll gain.

But the odd thing is that in these markets, the conventional wisdom of the crowd is usually right.

Even with token money, prediction markets have proven to be extremely reliable forecasters. Using real money, the Iowa Electronic Market for presidential elections has been uncannily accurate for many decades. According to Business Week article 12 years ago,

[IEM] predicted the vote totals of the past two Presidential elections within two-tenths of a percentage point, outperforming national polls. It also has closely tracked elections overseas, never wavering from Boris Yeltsin, for instance, as he won reelection in Russia.

in October 2006, CNN Money reported IEM’s predicted outcome for the mid-term elections, which was then a month away:

The Iowa Electronic Market, which offers contracts on the outcomes of political and economic events, says the percentage of investors in the 2006 Congressional Control market believing Republicans will hold full control of Congress has dropped to 39 percent from 58.5 percent on Sept. 28, when news was revealed about Rep. Mark Foley’s correspondence with pages. Those believing the Democrats will take full control of Congress have risen to 22.9 percent from 11.2 percent Sept. 29, the day the Florida Republican resigned.

The IEM market detected the swing in political moods that resulted in the Republican loss of Congress.

A few years earlier, in the summer of 2004, the IEM favored a Bush re-election win even when the pundits and polls showed Kerry in the lead. This out-of-sync prediction so puzzled many observers that some wondered (Salon article) if the IEM was systemically biased towards Republicans. But again, it was not bias, but simply accurate prediction; the IEM was uncannily accurate in forecasting Bush’s win.

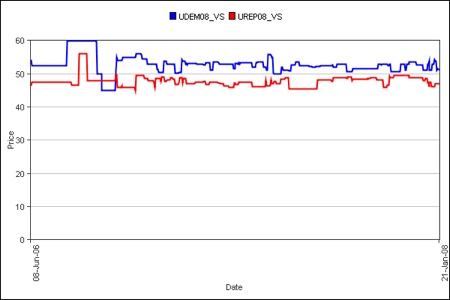

So what about this year’s presidential election? What does the oracle of the IEM say about the prospects of a Democrat or Republican president in 2008? As of yesterday, here are the price of contracts for each. It is still a close race, with the price of a Democrat president (blue) slightly higher than a Republican one (red). Of course we are 9 months away.

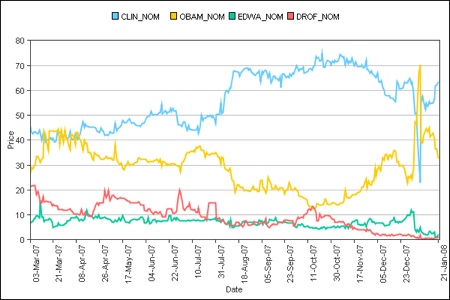

The price of party candidates is a lot more interesting. Below is the graph of the price of each of the major Democrat nominees winning the nomination. The recent double reversal between Clinton and Obama is clear, as is the sinking possibilities of the other contenders.

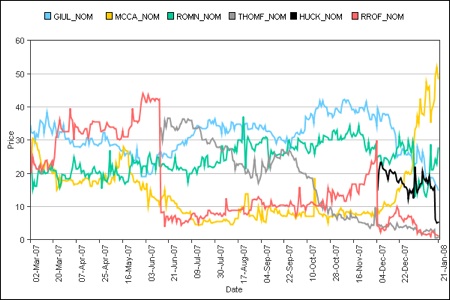

But the zig zags of the Democrats pale with the mess in the Republicans. Their prices are all over the map with very little clear trajectory, until very recently. For the first time, the price of a Republican candidate (McCain) breaks the 50 cent (half of the $1 value) threshold, while the others are sinking rapidly. According to the collective wisdom of the IEM, as of yesterday, the only other Republican in the race is Romney.

Anything can happen in the next 9 months. The IEM doesn’t see the future. It is merely a very quantifiable measure of aggregate expectations now. But because real money is at risk, people tend to bet on what they think will happen, vs. what they want to happen, and in aggregate, this method seems to yield better forecasts than polls or pundits.