Everything That Doesn’t Work Yet

[Translations: Japanese]

Alan Kay, a brilliant polymath who has worked at Atari, Xerox, Apple, and Disney, came up with as good a definition of technology as I’ve heard. “Technology,” Kay says, “is anything that was invented after you were born.” By that clever reckoning, automobiles, refrigerators, transistors, and nylon are not technologies in our eyes — just plain old stuff. But they were once technologies for my grandfather. By the same logic, CDs, the web, Mylar, cell phones, and GPS are authentic technologies for me – but not my kids! They’ll have their own technologies, invented in the last five minutes.

Danny Hillis, another polymath who used to work with Alan Kay, refined Kay’s definition a bit further in the 1990s, and a bit more usefully. “Technology,” Hillis says, “is everything that doesn’t work yet.” Buried in this sly definition is the insight that successful inventions disappear from our awareness. Electric motors were once technology – they were new and did not work well. As they evolved, they seem to disappear, even though they proliferated and were embedded by the scores into our homes and offices. They work perfectly, silently, unminded, so they no longer register as “technology.”

The satirist and novelist Douglas Adams further evolved Hillis and Kay’s definitions by suggesting a natural lifecycle for technologies. In a short essay in 1999 he proposed the world works like this:

1) everything that’s already in the world when you’re born is just normal;

2) anything that gets invented between then and before you turn thirty is incredibly exciting and creative and with any luck you can make a career out of it;

3) anything that gets invented after you’re thirty is against the natural order of things and the beginning of the end of civilisation as we know it until it’s been around for about ten years when it gradually turns out to be alright really.

Then with a very Doug Adams flourish, he adds:

Apply this list to movies, rock music, word processors and mobile phones to work out how old you are.

We no longer think of chairs as technology, we just think of them as chairs. But there was a time when we hadn’t worked out how many legs chairs should have, how tall they should be, and they would often ‘crash’ when we tried to use them. Before long, computers will be as trivial and plentiful as chairs (and a couple of decades or so after that, as sheets of paper or grains of sand) and we will cease to be aware of the things.

Adams is deliberately flip, but the German philosopher Heidegger suggested, in all seriousness, that “technology is not technological or machine-like.” For him technology was an “unhiding” – a revealing – of an inner reality that is revealed by mechanical embodiment. Further befuddlement can be found in the works of the French philosopher-poet Bernard Stiegler, who says that technology is “organized inorganic matter.” That doesn’t quite cover the brave new world of genetic engineering and GMOs, so we still lack a good working definition of the term.

When the Greeks used the word techne it meant something like art, skill, craft, or even crafty. Ingenuity would be close. But there wasn’t much interest in techne in ancient times and there’s not a single treatise on techne in the Greek corpus – with one exception. To the best of our knowledge the word techne was first joined to logos to yield the single term technelogos in Aristotle’s treatise on Rhetoric. Four times in this essay, Aristotle talks about technelogos, but in all four instance his meaning is unclear. Is he concerned with the “skill of words” or the “speech about art”? The term essentially disappeared after that.

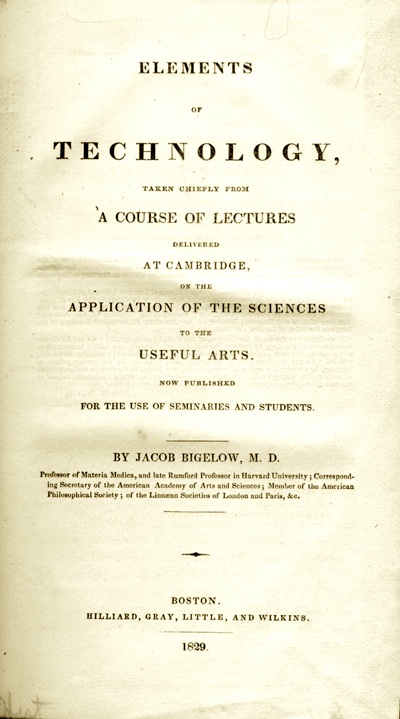

In 1829, Jacob Bigelow, an engineering professor at Cambridge University in Boston, thought it a good idea to round up all the “applied arts” courses being taught at his school and synthesize them into a unified curriculum. He gathered the studies of the sciences and techne of architecture, chemistry, metalwork, masonry, manufacturing and the like into one textbook. He gave this syllabus the title: Elements of Technology; taken chiefly from a course of lectures delivered at Cambridge of the Application of the Sciences to the Useful Arts. Now published for the use of seminaries and students.

Jacob Bigelow coined the word technology, as it is used in its modern meaning. (We don’t know if he picked it up from Aristotle’s Rhetoric, or merely constructed it from the Greek roots.) By the time he did in 1829, however, his world was chock full of things that had been invented after he was born, and that did not work well. There was technology but nobody knew it. In fact for many centuries in Europe and China inventors and engineers had been creating what we would label technology, but didn’t possess a word to describe the place of these inventions in their world.

Today, we still aren’t sure what this stuff is. We only know there is more of it.