Four Stages in the Internet of Things

[Translations: Japanese]

I’m making no bets whether the new buzz word “graph” will replace the still useful but overexposed terms of network and web. (I would have bet against the word “blog” ever being uttered by someone not smirking.) But it doesn’t matter. This short posting entitled the Giant Global Graph by Tim Berners-Lee, which blesses the hip use of “graph,” is the best summation of the semantic web I’ve seen yet — in part because he doesn’t talk about semantics.

The points he makes are worth paraphrasing. The following riff on his essay doubles as my summation of what I think the Semantic Web, or even Web 3.0 is about.

ONE

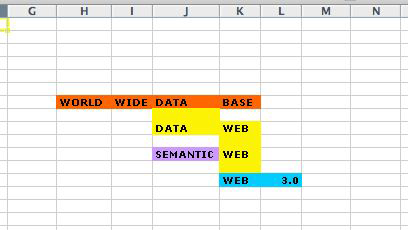

The first stage of this current communication evolution was linking up computers. We called that link-up the network of networks, or the internet. It was useful and boring. It was sort of like the phone system without phones. If you wanted to book an airplane flight the best you could do was connect to the airline’s computers. Active participants on this new system had to take one step toward openness. Computers on the internet had to be willing to forward other folk’s packets of data, and in the larger scheme an originator of bits did not have full control of its own packets (unlike the phone system).

TWO

The second stage of digital communication was linking up documents and pages. That’s the web. Now you could connect to a page or document about your airline flight rather than just the company. There was a refinement in resolution that make the system far more useful. And to play in this arena, a player had to be open to sharing their page. Hiding pages behind passwords was generally self-defeating. Neither could you restrict who linked to your documents, as many neophytes mistakenly try to do. You also have to be open to your content being copied and pasted a bit, and to be copied in full as an index by search engines. This was another step in letting go. But the value of connecting was generally widely appreciated.

THREE

We are now at the end of the beginning of the third stage. What happens here is that after linking and sharing computers, then linking and sharing documents, we are linking and sharing data in those documents. We are sharing and linking the subjects and meaning of what those documents are about. Instead of connecting to the airline’s computer, or later to the flight page, we can connect directly to the flight’s information itself. The data is unbundled and in a form that can be read by any device on the web. Indeed, when done correctly it can be comprehended by the web itself since it is not rendered in English but in a general semantic form. That universal form is something that will live in a database. In fact, you could think of this stage as the World Wide Database.

Having access to the data of our world is liberating and made possible by lots of 3-letter technologies: XML, RSS, API, RDF, OWL. These are standards of communicating and sharing data on the web. It’s been amazing how much can be accomplished just by zipping content between websites via RSS. Another tremendously unappreciated enabling technology is the API. This gateway allows controlled sharing of vast archives of data, unleashing the data’s power via the usual network effects — the more that use it the more valuable it becomes. And just as in the first two stages, folks struggle to overcome their fear of sharing. Sharing data feels closer to us than sharing either our computers or our documents. But learning how to share data is what the next web will be about. Those who are able to let go and understand that all the real value in this next stage will be built on the emergent value that comes from deep interlinking, deep interconnecting, and freely (as is reasonable) releasing your precious data, those will be the technologies and organizations who gain the most.

Here’s how Tim Berners-Lee puts it himself:

The less inviting side of sharing is losing some control. Indeed, at each layer — Net, Web, or Graph — we have ceded some control for greater benefits… Letting your data connect to other people’s data is a bit about letting go in that sense. It is still not about giving to people data which they don’t have a right to. It is about letting it be connected to data from peer sites. It is about letting it be joined to data from other applications.

FOUR

BTW, I don’t think this third stage is the end of history, or the end of the story. (I have learned to be suspicious of any history that comes in threes). I think we can see a fourth stage beyond. That fourth stage is the drift towards linking up the things themselves. You want all the data about a thing to be embedded into the thing. You want location information embedded at, or in, the location itself. You actually want to connect not to the airline’s computer, nor to the airline’s flight page, nor to the flight data, but to the flight itself. Ideally, we would connect to the embedded processing and raw information in the airplane, in your particular seat, at the airport’s slot — the entire complex of items and services we call “the flight.” What we ultimately want is an internet of things.

SEMANTIC WEB

That internet of things, where everything we make contains a sliver of connection, is still a ways off, although I believe we will create it. The internet of data — the world wide database — is quickening right now. As far as I can tell, this is what people mean by the Semantic Web. Because in order to be shared, information is extracted from natural language, reduced to its distinct informational elements, and tagged into a database. In this foundational form it can then be re-assembled into meaningful (semantic) informational molecules in thousands of new ways that is not possible to do when it remains in a flat un-annotated primitive document.

I believe this shareable extraction of data is also what people mean by Web 3.0. In this version of the webosphere data surges, flows, and expands across websites as if it were acting within one large database, or within one large machine. My site solicits a steady stream of data from Alice and Bob; it then adds value by structuring the data in a new (semantic) way, and then I issue my own streams of organized data, to be consumed by others as raw data. This ecosystem of data runs on an open transport system, and consensual protocols, even though not all data is shared or public.

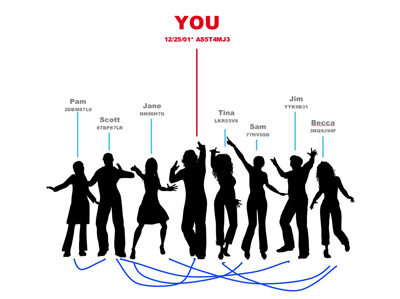

An operational Semantic Web, or World Wide Database, or Giant Global Graph, or Web 3.0, will make possible millions of seemingly smarter services. I won’t have to re-tell each website who my friends are; once will be enough. If my name shows up in text, it will know it’s me. My town will be a town on the web — a place with definable characters — and not just another word. That ubiquity enables any references to my town to link to the actual information about the town. The apparent smarter nature of the web will be due to the fact that the web will “know” more. Not in a conscious way, but in a programatic way. Concepts and items represented on the web will point to each other and know about each other — in a fundamental way they do not right now.

The details matter. Which protocol will triumph, which standard prevail, which company maintain the majority? — these are the unknowns. Policy details matter too. Documents and computers as property are a lot less problematic than data as property. Data is notoriously hard to own. And then there is the slippery notion of identity. If the web knows you are always you, who are you? If the price of total personal service is total personal transparency, is that any different than total personal surveillance?

The smartness of this thing will unnerve many people. Even though it will be miles from anything human, the fact that it will know anything at all, and know anything about them, will make many folks jump back. And push back. I’m counting on the fact that kids will love it.