Google-Unique Names

[Translations: Japanese]

You are unique, just like everyone. Shouldn’t our names be too?

My name is not. According to the database How Many of Me, which calculates the likely incidence of first/last name combinations, 1,000 other guys in the US have my name, Kevin Kelly. I think that is a major undercount because I personally have met dozens of others with my name, surely only a fraction of those born with it. A website set up as a clearing house for all the Kevin Kellys on the web lists nearly one hundred people with my name, which can’t possibly be one tenth of those named.

We humans have names to distinguish us, yet we paradoxically keep recycling the same ones. In the old days, say up to 50 years ago, a re-combination of familiar names might be unique and sufficient in a small town. But as small town life became less common and urban life more common, names had to be more uncommon. Today, in the global village and a universal Facebook, having a globally unique name makes more sense.

With such a common fist/last name attached to my face, I wanted my children to have unique names. They were born before Google, but the way I would put it today, I wanted them to have Google-unique names.

Names are funny things. They want to be different, but not too different. I’ve met several people recently who have numbers in their legal names. That’s different. I have a friend who’s son’s legal first name is Q. That’s unique. Some folks has deliberately unpronounceable and thereby incredibly unique names, but at the cost of low communication (spell that again please?). Finding a balance between too-different for comfort and just-different enough for unique is an art. Ask anyone trying to come up with a company or website name.

People’s names are more complicated still because we often want a name to be a “name” word. Like John or Kevin. In English we have certain words which are first and last names, and are only used as names. There is nothing else named Kevin except people. (ANd these days, they are losing some of their gender specificity. I’ve met one girl Kevin. I am sure there is at least one female Kevin Kelly. )

We would find it funny or uncomfortable for someone to be officially named “watermelon” or “guitar” or “nervous” — although we are fine with those as nicknames. But in Chinese, and other cultures, name words are often ordinary words like these. In fact elsewhere folks are formally named melon and guitar in their local tongue. We see that same impulse in the English names that hundreds of millions of Chinese are adopting in their move toward globalization. Online you’ll find Bicycle Chen, Paper Wang, or Promise Lin. Any linguist will tell you that our western names all began as ordinary words, which lost their meanings over time, except for a few like Baker, Smith, Son, etc whose meaning we can still discern. Centuries later name words most communicate “nameness” and sometimes, ethnicity.

The balance between different and too different in a name (and other creations as well) is really a trade off between uniqueness and meaning. In choosing the names for our kids we tried to balance communicating uniquenss (“Zorr”!) and communicating meaning (“Tom,” safe American). We retained meaning in our own family by constraining the choice to names that meant something both in Irish (my line) and Chinese (my wife’s line), while still sounding “name-ish” to teachers and friends — and being Google-unique. If you google our kids names Kaileen Kelly, Ting Kelly and Tywen Kelly, you get them.

(I should be clear that having a Google-unique name is not the same thing as being easily found on Google. You could have a unique name, do nothing, and not be found. Or you could be named John Smith and be found on the first page because you were an active writer. See this Wall Street Journal article on the economic issues around having a searchable name.)

Company names must make the same tradeoffs in the balance between uniqueness and communication. As a name, “Apple” is nothing unique (ask the Beatles), but it does communicate certain feelings and notions. On the other hand Xzdggr communicates very little, even though it is unique. One way many companies have navigated this compromise is by adopting abbreviations and unique spellings of common words (like Flickr, Digg, etc) to both stand alone and communicate.

I expect personal names to continue to drift in this direction. I’ve been signing books and I’ve learned to ask each time “how do you spell that” no matter how common the name, because one in five times, the person will spell it non-traditionally. There have always been a few with startling weird names, but in general names are becoming more diverse. With the global remix, intermarriage, and constant migration, “normal” first names in schools in the US and Europe will as likely be Arabic, Indian, or Korean as they would be English, or Irish.

There are more than enough words in our dictionaries for every person on earth to have a unique dual name, even if you keep the tradition of maintaing a family name. I understand the attraction of continuing previous names in a family (I was originally named after my father), but the virtues of having a search-unique name will continue to grow.

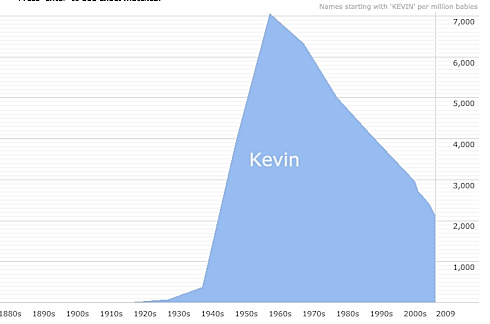

We are very creative in naming our pets and companies but less so in naming our children. We now have the tools for detecting unique names and an increase acceptance of them. Yes, please forgive us, we will see Jennifr, Thms, Connr, 3er, Zorr and more commercial brand names for kids. Unique names for the living don’t have to be new names; they could be old out-of-fashion names resurrected. (See NameVoyager for the rise and fall of name popularity in the US.)

Yep, 1952 peak, that’s when I was born.

But my guess is that the complicated process of naming things – checking to see who or what else is named the same, what names are “available,” considering how names work in other cultures — will become so familiar to people as they name their band, their book, their pet, their blog, their start up — that they will take some of that same approach when they name their children.

At the same time our culture will more and more demand unique names. As Clive Thompson points out in his article on Googleable names: “Ask.com says that 7% of all its searches are for personal names; meanwhile, 80% of executive recruiters do an online search for applicants’ names, and 40% of people say they’ve used search engines to hunt down long-lost acquaintances.” This state of affairs is not true in many countries and cultures today, even technologically advanced ones like Germany or France or Scandinavia, where names have to conform to certain rules. No illegal names like “@” or “Dwezzle” or “4Real” or “Devil” or “Anus” (all ones that have been rejected.) We are dealing with children after all, and in theory a name lasts a lifetime. And every system, even the adhoc internet, has legal naming rules.

But if we make changing a name as easy as changing a url, what’s illegal should narrow. This won’t happen overnight. But I’m guessing that a century hence the average newborn will get a name that is unique among both the living and the dead. I think that will make the world more interesting.

By logical extension, there may come a time when a country/state/city declares that unique names are mandatory. You must select a name that no one else has. Obviously this improbable scenario can only work if there is a unified database of names in use — which does not seem so far fetched. Your name would thus serve something similar to an unique ID number. I could live with that.