Governing Sovereign Wealth Flows

You’ll be hearing more about sovereign wealth funds and flows in the future.

A sovereign wealth fund is a huge heap of money that is controlled by a nation — say Singapore or Saudi Arabia — rather than by a private transnational company. The latter is called private equity funds and their investments have been prime movers in global finance for decades. Some of the largest banks and finance companies that are in the current news cycle, like Bear Stearns, or UBS, are good examples of private money. They buy and sell business across national borders.

But as large as these financial behemoths are they are small compared to the largest sovereign funds. The total amount of private funds sloshing around the world is in the hundreds of billions, whereas sovereign funds — the money controlled by nations looking for investments — is $2.5 trillion. Sovereign funds are common in countries where the division between state and capitalism is thin and blurred. According to the New York Times in their article The Leveraged Planet, the amount of sovereign controlled wealth is expected to rise to $12 trillion by 2015. These funds also buy and sell businesses across borders but since their owners are other nations, or nation-state organizations, the implications of their scale and intent are proving enormous.

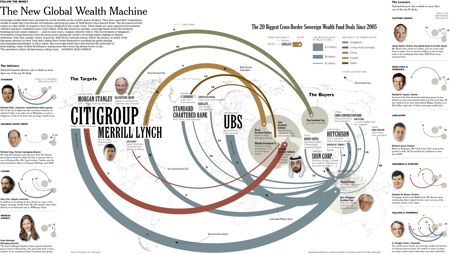

A wonderful New York Times graphic showing the global flows of sovereign wealth.

Sovereign wealth is not new. It is simply more visible now, and because of $100/barrel oil, the funds flowing into nationalized funds are in the trillion dollar range.

There is a second reason why sovereign wealth is getting a lot of attention. For many years these funds have been the ones buying US debt. As Americans consume, foreign countries lend us the money. But now for a number of reasons, they are no longer so keen on the US. Protectionist elements in the US object to sovereign funds owning key US companies, and the dizzy devaluation of the dollar has driven many sovereign investors to the Euro. Some chiefs of these private equity funds in the Mid-East can buy US assets but have trouble getting a visa to visit the States. So why bother with the US?

At the same time the flows of these funds, pumped up by petro-dollars and export purchases, are getting huger, weirder, and more uncertain. Most importantly, they are basically unregulated.

There are calls for some kind of minimal rules for this global marketplace. George Soros, a big player in the private equity arm of this game, says, “The financial system needs a global sherif.”

In the past, calls for global sherifs have not amounted to anything. Americans, like other nationals, have a keen aversion to anyone telling them what to do as a nation. National rights, like national security, is considered sacred. There’s been a long history which claims that nothing should trump sovereignty. In the near future that may be regarded as a quaint sentiment.

Markets need a minimum set of enforceable rules. The amazing robust market of strangers that we call Ebay works with very few rules because in the last resort those few rules are upheld by the national sherif — the US sovereign state.

There is one planetary-scale marketplace, hinted at by Thomas Friedman’s “The World Is Flat” which contains the flow of goods and jobs around the world. Work migrates to where it can find the best financing; workers migrate to where they can find the best jobs; consumers migrate to where they get the best deals.

Behind this is another planetary-scale marketplace which moves the investment funds made by high-priced energy, or successful cheap labor. Here flows the 2.5 trillion dollars. The scale of these money flows overwhelm any other global finance dynamic. One might predict that in the near future these quasi-national flows will dictate your economic environment more than your local, regional, or even national policies will.

This unregulated marketplace is scary, even for the players. Since minimally regulated markets make everyone more money by reducing some of the risk, there is a HUGE incentive among the players to install some basic minimal rules. Rules that can be enforced. By someone with clout.

The key question now before these moneyed players (mostly the nation states themselves) is whether these minimal rules can be cobbled together in a decentralized pan-national way, with a few super-nations playing cop (sort of like it has been, only now with China in the lead). Or will the new global game require an actual supra-national power, some kind of global financial sherif?

The political US is balking at either scenario — China leading, or a super transnational entity — and it doesn’t like the idea of unregulated large ownership investments by other “foreign” nations either, so the rise of sovereign wealth flows is causing alarm. On the other hand, money, the real money is seeking opportunities in the new order.

Nothing about the current arrangement is stable. The mortgage crisis is merely a symptom of a much large disruption: the emergence of a global flow of money in need of some global level regulation. The greedy bankers themselves want it. They need some minimal global enforceable rules.

Something is happening here, but we don’t know what it is, do we Mr. Jones?