Immortal Technologies

One of my hypothesis is that species of technology, unlike species in biology, do not go extinct. When I really look at supposed extinct species of technology, I find they still survive in some fashion. A close examination of by-gone technologies shows that somewhere on the planet someone is still producing it. A technique or artifact may be rare in the developed world but quite common in the developing world. For instance, Burma is full of ox-cart technology; basketry is ubiquitous in most of Africa; hand spinning still thriving in Bolivia. A technology may be enthusiastically embraced by a heritage-based minority in modern society, if only for traditional satisfaction. Consider the traditional ways of the Amish, or modern tribal communities. Often old technology is obsolete, that is, it is not very ubiquitous or second rate, but it still may be in small-time use, as many old-fashioned ways are.

In my own travels around the world I was often struck by how resilient ancient technologies were, how they were first choices where power and modern resources were scarce. It seemed to me as if no technologies ever disappeared. I was challenged on this conclusion by a highly regarded historian of technology who told me without thinking, “Look, they don’t make steam-powered automobiles anymore.” Well, within a few clicks on Google I very quickly located folks who are making BRAND NEW parts for Stanley steam-powered cars. Nice shiny copper values, pistons, whatever you need. With enough money you could put together an entirely new steam-power car. And of course thousand of hobbyists are still bolting together steam powered vehicles, and hundreds of more are keeping old ones running. Steam-power is very much an intact, though uncommon, species of technology.

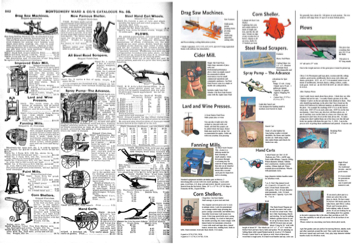

I decided to see how many old technologies a post-modern urban citizen living in a cosmopolitan city (like San Francisco) could lay his hands on. I decided to try to get all the products on a sample page from the 1898 Montgomery Ward catalog. One hundred years ago, there was no electricity, no internal combustion engines, few highways, and little communication except via the post office – upon which the Montgomery Ward catalog operated. A substantially different technological paradigm reigned at this time. The faded newsprint of my reproduction catalog had the air of a mausoleum. However, even on first survey it was clear that most of the thousand of items for sale one hundred years ago, as cataloged by this wish book, were still sold now. Although the styling is different, the underlying technology, function, and form are the same. A pair of leather boots with doodads is still a leather boot.

Flipping through its 600 pages, I select one fairly typical page that featured agricultural implements, thinking that these types of things would be far harder to find today than, say, the stove pots, lamps, clocks, pens, and hammers that populate the rest of the pages. Farm tools seemed like certain dinosaurs. Who needs a hand-powered corn cob sheller, or a paint mill?

It’s a no-brainer to find artifacts like these as antiques on eBay. My test was to find newly manufactured versions, since this would show that these species were still viable. I used the web to search for them simply out of laziness. Much to my surprise I was able to find every single item listed on this page of the 1898 Montgomery Ward catalog, available new and sold on the web. I show here both pages, with current incarnations of old technologies.

I haven’t done the research to find out the reason for survival of each item, but I suspect that most of these tools share a similar story. While working farms have shed these obsolete tools entirely, and are almost completely automated, we still garden with very primitive hand tools simply because they work. As long as backyard tomatoes taste better than farmed ones, the elemental hoe will survive. And apparently, there’s pleasure in harvesting some crops by hand, even in bulk. I suspect a few of these items may be bought by the Amish and other back-to-the-landers who find virtue in doing things without oil-fed machinery.

Let’s take the oldest technology I can image: a flint knife or stone ax. You can buy a brand new flint knife, flaked by hand and carefully mounted on an antler-horn handle by a winding of leather straps for about $50. In every respect it is the same technology as a flint knife made 30,000 years ago. In the highlands of New Guinea, tribesman were making stone axes for their own use until the 1960s. They still make stone axes the same way for tourists now. And stone-ax aficionados study them. There is an unbroken chain of knowledge that has kept this stone age technology alive. Today, in the US alone there are 5,000 amateurs who knap fresh arrowhead points by hand. They meet on weekends, exchange tips in flint-knapping clubs, and sell their points to souvenir brokers. John Whittaker, a professional archeologist and flint-knapper himself, has studied these amateurs and estimate that they produce over one million brand new spear and arrow points per year. These new points are indistinguishable, even to experts like Whittaker, from authentic ancient ones.

I have been unable to locate very many technologies that have truly disappeared from the face of the earth. There is the famous lost technology of Greek Fire mentioned by several ancient historians. They record that the Greeks flung molten balls of burning something onto enemy ships and forts which had incredible incendiary powers. But no one has been able to determine what it was, and if it was something that we no longer have (there are other flame throwing devices). The Inca system of accounting using knots on a string, called Quippu, is pretty much lost as well. We have some antique samples, but no knowledge of how they were actually used. In the 1990s, science fiction authors Bruce Sterling and Richard Kadrey

compiled a list of “dead media” to highlight the ephemeral nature of popular gadgetry. Recently vanished gizmos such as the Commodore 64 or the Atari computers were added to a long list of older species such as lantern slide projectors, or a telharmonium. However, if you go to find them, most of the items on this list aren’t dead. Some of the oldest media technologies are maintained by basement tinkers and crazy amateur enthusiasts. And much of the more recent technologies are still in production, but under different brand names and configurations. For instance a lot of the technology of early computers is now found inside your watch or toys.

With very few exceptions, technologies don’t die. In this way they differ from biological species, which in the long-term inevitably do go extinct. Technologies are idea-based, and culture is their memory. They can be resurrected if forgotten, and can be recorded (by increasingly better means) so that they won’t be overlooked. Technologies are forever.