Natural History of a New Idea

The notion that ideas have lifecycles has many antecedents. Various people get credit with first articulating it. Here is my version:

The Natural History of a New Idea:

1) Outright wacko.

“This is worthless nonsense”

2) Odd but unproven.

“This is an interesting, but perverse, point of view.”

3) True but trivial.

“This may be correct, but it is quite unimportant.”

4) Obvious.

“What’s new? This is what we’ve said all along.”

Apply to your favorite example.

I’ve seen this abbreviated to: “Crazy. Crazy. Crazy. Obvious.” But I think it’s more useful to pay attention to the gradations. Where along this scale is your idea?

Here is a real example from Norman Shumway discussing the rocky progress of heart transplantation. It took the crazy idea 22 years, between 1960 and 1982, before it was widely accepted.

1 Initial stage: “Won’t work; been tried before.”

2 After successful experiments in animals: “Won’t translate to man.”

3 After 1 successful clinical patient: “Very lucky; doubt if patient really needed transplant.”

4 After 4 or 5 clinical successes: “Highly experimental, too risky, immoral, unethical; I understand they have had a number of deaths they are not reporting.”

5 After 10 to 15 patients: “May succeed occasionally in carefully selected cases but very few patients really need an operation anyway.”

6 After a large series of successes: “So and so has been unable to duplicate their results. I hear that a number of their patients are now dying late death.”

7 Final stage: “This is a very fine contribution. A straightforward solution to a difficult problem. I predicted this. In fact, in 1939 I had the same idea. Of course, we didn’t publish anything. We had no cyclosporin.”

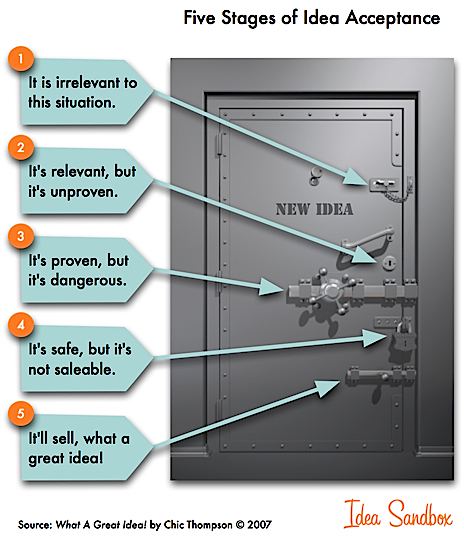

Another version from What a Great Idea! by Chic Thompson