One Dead Media

One of my suppositions is that technologies rarely go extinct — on the global level. Usually someone, somewhere will continue to employ the most ancient technology. There are probably more people making swords by hand now than in the past. On any given weekend in the US there will be a gathering of weekend flint knappers churning out mounds of magnificent arrow heads, using the exact technology of the stone age. Online you can buy new valves for a Stanley steam powered car, or leather parts for a horse drawn buggy, just as you could 100 years ago. In some parts of Africa and Asia any ancient tool is still manufactured in ancient ways. It is hard to find an old technology that is not available in any form any where on earth.

But today I may have found one. Alex Wright’s story in the New York Times about Paul Otlet, the little-known Belgian who worked out an early version of hypertext (see my review of a documentary about him in True Films) prompted a reader to point out a system similar to Otlet’s that was once available commercially in the US.

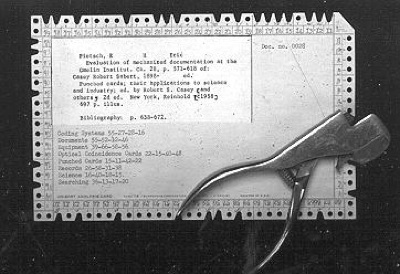

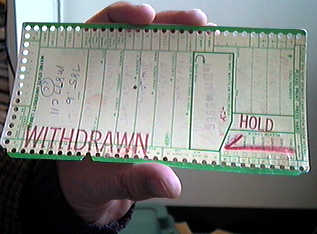

Edge-notched cards were invented in 1896. These are index cards with holes on their edges, which can be selectively slotted to indicate traits or categories, or in our language today, to act as a field. Before the advent of computers were one of the few ways you could sort large databases for more than one term at once. In computer science terms, you could do a “logical OR” operation. This ability of the system to sort and link prompted Douglas Engelbart in 1962 to suggest these cards could impliement part of the Memex vision of hypertext.

The “unit records” here, unlike those in the Memex example, are generally scraps of typed or handwritten text on IBM-card sized edge-notchable cards. These represent little “kernels” of data, thought, fact, consideration concepts, ideas, worries, etc., that are relevant to a given problem… Each such specific problem area has its notecards kept in a separate deck, and for each such deck there is a master card with descriptors associated with individual holes about the periphery of the card. There is a field of holes reserved for notch coding the serial number of a reference from which the note on a card may have been taken, or the serial number corresponding to an individual from whom the information came directly (including a code for myself, for self-generated thoughts).

In the US these cards were sold as McBee Keysort Cards and InDecks Information Retrieval cards. McBee cards were often used in libraries to keep track of books in interlibrary loan programs.

These cards were used by Stewart Brand in managing the creation of the Last Whole Earth Catalog in 1975, which is where I first encountered them. Here is what he said about them at the time:

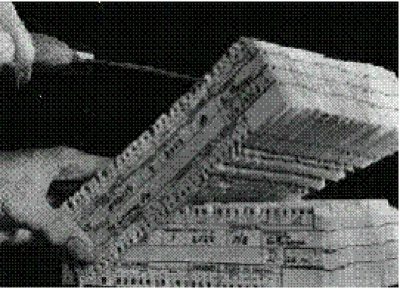

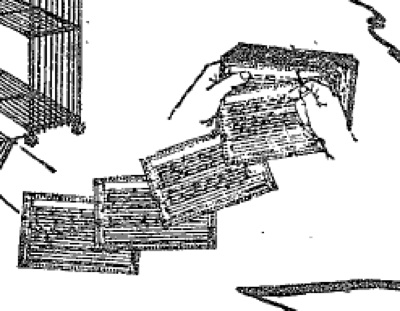

What do you have a lot of? Students, subscribers, notes, books, records, clients, projects? Once you’re past 50 or 100 of whatever, it’s tough to keep track, time to externalize your store and retrieve system. One handy method this side of a high-rent computer is Indecks. It’s funky and functional: cards with a lot of holes in the edges, a long blunt needle, and a notcher. Run the needle through a hole in a bunch of cards, lift, and the cards notched in that hole don’t rise; they fall out. So you don’t have to keep the cards in order. You can sort them by feature, number, alphabetically or whatever; just poke, fan, lift and catch. Indecks is cheaper than the McBee sysem we used to list. We’ve used the McBee cards to manipulate (edit) and keep track of the 3000 or so items in this CATALOG. They’ve meant the difference between partial and complete insanity.

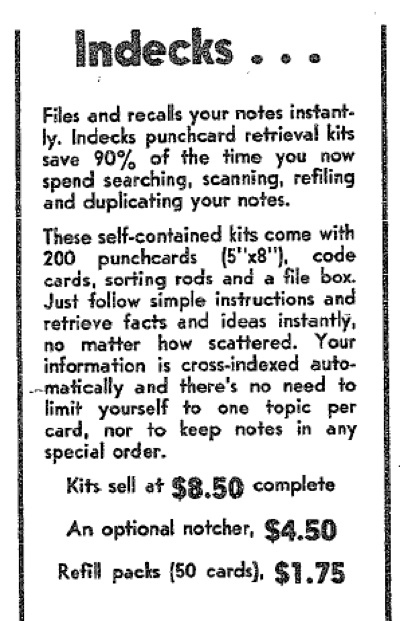

This card sorting system was sold to graduate students, and professionals with data sorting needs such as field workers, catalogers, and nerdy people. In short anyone who today might be FileMaker Pro. An advertisement in the September 23, 1966 issue of MIT’s The Tech offers:

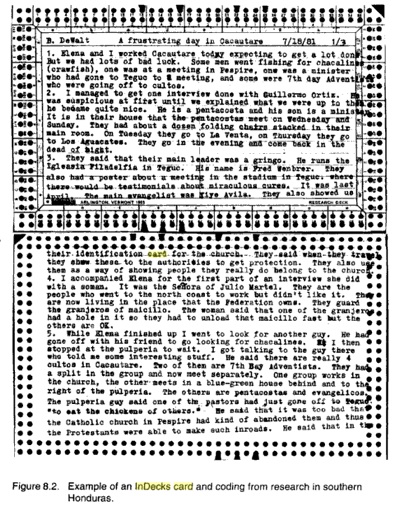

McBee and InDecks cards took a bit of fussy attention to make them work. Here is a description from Participant Observation: A Guide for Fieldworkers by DeWalt and DeWalt on how field researches used the cards.

The cards were “coded” by punching out the holes such that when a “knitting needle” was inserted into a particular hole in a stack of cards and shaken, the “coded” cards would fall to the floor. You could search for 2 codes simultaneously by using two knitting needles. For example on the card reproduced in figure 8.2 [below], the information has been coded using the gross codes contained in the Outline of Cultural Materials… Thus, information contained on this card is coded for the categories for research methods (12), demography (16), food quest (22), food processing (25), sickness (75), religious beliefs (77), and ecclesiastical organization (79). Needless to say, coding the information, punching out the holes, and retrieving information coded in this manner was cumbersome. It was almost more efficient to use the century-old system of marginal notes…

Pete Bell, co-founder of Endeca, a search and navigation technology, sent along this reference to the beginnings of the McBee way of knowledge:

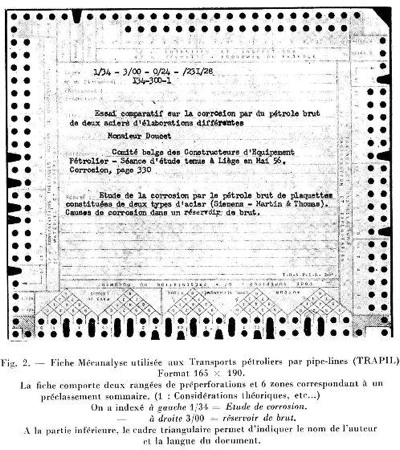

Otlet’s “steampunk hypertext” would not have scaled – from an information science standpoint, forget mechanically — but one of his contemporaries envisioned a way to browse information that did. Known today as the father of library science, S.R. Ranganathan was an Indian mystic and mathematician that in the 1930s saw the coming failure of the Dewey Decimal System to scale. He envisioned a better way to classify knowledge known as the Colon Classification System. And while Google might be the most popular way to search information today, the most popular way to browse information, besides hypertext, is on a faceted navigation system, whose roots are in Ranganathan. Below are pics of its steampunk predecessors.

This is an French edge-notched card, which permits faceted navigation.

To clarify what faceted navigation is, I offer this summary from Wikipedia:

The most prominent use of faceted classification is in faceted navigation systems that enable a user to navigate information hierarchically, going from a category to its sub-categories, but choosing the order in which the categories are presented. This contrasts with traditional taxonomies in which the hierarchy of categories is fixed and unchanging. For example, a traditional restaurant guide might group restaurants first by location, then by type, price, rating, awards, ambiance, and amenities. In a faceted system, a user might decide first to divide the restaurants by price, and then by location and then by type, while another user could first sort the restaurants by type and then by awards. Thus, faceted navigation, like taxonomic navigation, guides users by showing them available categories (or facets), but does not require them to browse through a hierarchy that may not precisely suit their needs or way of thinking.

A similar faceted approach is taken by computer-based field guides to wildlife identification. The old style key for birds require you to go down a path of forking questions: Does it have web feet or not? Is it bigger than a pigeon or not? Does it have a downy crest or not? This hierarchical path can trip you up if you mistake an early step. It will then send you down the wrong path to the wrong identification. Much better is a faceted navigation based on a matrix, where you answer any of the the forks you can, in any order, and then the computer will sort you the most likely answer. The edge-notched McBee and InDeck cards and Colon Classification contained the seeds of this matrix/faceted navigation.

But prescient as it was, and as cool as these cards were, I searched the Net today for any sign of InDecks and was surprised to find no sellers on eBay, no fan sites, no collector sites, no historical web pages, and no evidence that anyone is still using them. They are gone. Blasted out by the first computers. Bruce Sterling lists them in his Dead Media file, a catalog of defunct media devices and platforms. They seem to be verifiably extinct.

Unless I am wrong. If you know of anywhere in the world these edge-slotted cards are still be used or manufactured, please write, and I’ll be happy to announce the news of their survival.