Open-Source DNA

As far as I can tell, if you visited my home today it is legal for me to slyly snatch an “abandoned” sample of DNA from you (from the lip of a cup, a fallen hair, etc.), sequence it in full, and publish your DNA online for the world to read. Of course I wouldn’t do that, but in April 2008, a seller on eBay peddled the remains of Barak Obama’s restaurant breakfast claiming that “his DNA is on the silverware.”

In England a new law prohibiting “DNA theft” makes this stealthy genetic sequencing illegal. But in the US only 8 states have any restrictions at all on sequencing others’ DNA (California is not one of them), and these restrictions are neither clear, consistent, nor absolute. (New Scientist is doing fantastic investigative reporting on the muddy state of the legal status of stealthy DNA sequencing.) Anne Wojcicki, the co-founder of the consumer DNA sequencing service 23andme told me that one of the reasons why their service requires you to fill a tube with saliva in order to get your DNA sequenced (I found it’s a minor biological feat to fill one of these with spit) is to prevent stealthy sequencing. This amount of saliva can’t be found abandoned. But many other labs, particularly forensic labs, don’t require massive gobs of protein and can work with minute amounts you might find on silverware.

It is virtually certain that most US states, if not the federal government, will rush to pass laws prohibiting stealthy DNA sequencing. There is a modern hysteria about DNA that goes in many directions. In this particular case, the initial push against “DNA theft” is being driven by two cultural taboos: paternity and sexual relations. The pioneering DNA theft law enacted by the UK was prompted by an alleged 2002 plot “to steal hair from Prince Harry to test whether he was the son of James Hewitt, a former lover of Princess Diana.” Laws in Germany were ignited by hostile attempts of feuding adults to claim paternity or non-paternity using “abandoned DNA” from children. And suspecting spouses hire labs to detect ‘foreign” DNA in underwear as evidence of infidelity.

Because DNA is seen as conveying not only paternity, and sexual activity, but also the blueprints to each person’s persona, the idea of someone else “capturing” it feels wrong. We currently perceive our DNA to be a personal code that contains our past, present and future. If we could just unlock it, we’d know our destiny. And at the same time, we’d better understand our current identity. I avidly encourage everyone to get their DNA sequenced, but I think the benefits are not what we currently believe they are, and I think the idea that these codes encapsulate us is close to superstition. For some folks, the fear of having your DNA stolen is akin to the fear by many tribal people of having their soul stolen by photography. I would argue that getting your DNA sequenced is very much like getting your photo taken. The camera takes your picture and not your soul. And your picture is well… your “picture” is not really yours.

Your DNA is not really yours, either. That statement is counterintuitive for some and stake-burning heretical for others. First, we know that 99.99% of the code in your cells is also in mine. We are 99.99% identical. There are very few genes that are unique to you. Probably none. The same can be said of our faces. But what our faces portray is the unique combination, or arrangement of very common parts. Humans have an uncanny ability to distinguish the less than .01% difference among faces and declare them unique. So we talk about “our” face, even though we share most, if not all of it with others in our extended family. To species outside of humans we probably look like identical penguins.

But while your face is unique in a very narrow sense, and thus “yours” it is less “yours” in terms of ownership that it appears. It is the most public part of you. You are required to display it as ID. We use faces to track each other and as an interface to each other, if I may use such technical language. I have some rights to capture your image in public. Your face is sort of “ours” in many ways.

I think in the long run (maybe after the next 50 years) our DNA profile will go the same way our image profile has. Our DNA sequence will likely become as public as our faces. Perhaps not all of it, in the way that parts of our bodies are covered, but most of it.

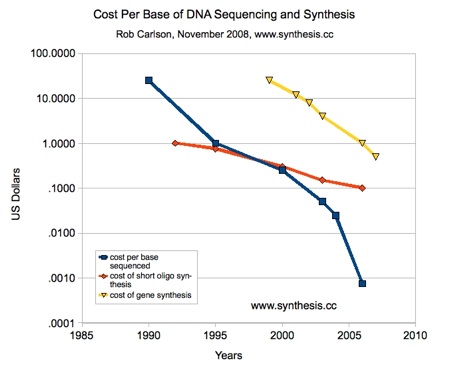

Right now, laws can regulate DNA sequencing because this work must be done by big machines owned by legit companies: the Navigenics of the world. Think gigantic printing presses. But these large, capital-intensive, and easily regulated machines will be disappearing as the price of DNA sequencing keeps dropping. Sequencing is dropping in prices as fast as computer chips (because that is what powers them). The price of gene code is plunging in half every 20 months, which is roughly the 18 months of Moore’s Law. In about 25 years, it will cost only a few cents to get your entire chromosomes done. At first we’ll decipher them once in our life, then once a year and then once a day, in order to detect the effects of environmental toxins.

Chart by Rob Carlson

Up to 70% of the fish sold in markets and restaurants today are misidentified by species. Catfish is sold as Grouper fillet and so on. When we have our handy tricorder species identifier in hand at the supermarket, we’ll be able to label the exact foods we eat with their province and pathway to our mouths. And anything that can identify one species can identify another (with the proper software).

This means that just as computers make regulation of the press and control of copies impossible, computers embedded in DNA-tricorder devices will make regulation of DNA sequencing as impossible to control. Anyone will be able to sequence anything they want.

We will have regulations preventing the publication of sequences which some one else wishes to keep private but I suspect culture will route around this. Long before we have daily DNA sequences, we’ll begin to share our code fervently. The big surprise for me has been how eager the early adopters of personal genomics have been to share their DNA. Privacy experts have argued that nothing is so private as our genes, but I am finding that nothing is so widely sharable as our genes. Since after all, we share most of them.

Right now, there is a belief that genes are destiny, but as Steven Pinker stated so well in a recent New York Times Magazine story (“My Genome, My Self“), while our genes collectively shape us more than anything else, individual genes don’t tell us much. It is a bit like prime factors in mathematics. Any two primes (any two genes) multiplied will give you a predetermined and precise outcome each time. But trying to unravel a given outcome into its two unknown prime factors (genes) is so difficult that this operation of “deciphering the genes of the product” is the basis for most encryption. Genes shape us, but determining which gene shapes what part of us in particular is very very difficult. There are few single-gene or even double-gene mutations which cause curable diseases. Most ills are far more genetically complicated.

The only way we’ll decipher genes is through the brute force mapping of genes to bodies and behavior, which will require disclosing and sharing our genetic codes. Mapping genes without tracing their effects upon a body will not be very valuable. But each time a person reveals their genes to the science collective and starts to correlate their genes to their own bodies and behavior, the more valuable their sequence gets. This is the very recipe for the increasing returns and “network effects” that we’ve seen unleash the internet, the web and cell phones. The more who join, the better it gets. The more folks that sequence and share, the more valuable your sequence becomes. Increasing returns and network effects penalize early adopters and favors the late, but once the cycle quietly begins, it can suddenly pass the tipping point and gallop into a stampede.

Eventually, the cost of sequencing will be so cheap, that it will become mandatory for certain purposes. For instance, thousands of effective therapeutic medicines today cannot be sold because they induce toxic side effects in some people. Sometimes the sensitive will share a cluster of genes. If this group can be excluded using gene testing, the otherwise effective medicine can be prescribed to the rest. Several drugs on the market today already require genetic screening for this purpose. Because such screening can save pharamseutical companies billions of dollars in drug development, I predict the pharmacy companies will fund DNA sequencing; they will pay the fees for sequencing.

There will surely be people who will not share any part of their genome with anyone under any circumstances. That’s okay. But great benefits will accrue to those who are willing to share their genome. By making their biological source code open, a person allows others to “work” on their kernel, to mutually find and remedy bugs, to share investigations into rare bits, to pool behavior results, to identify cohorts and ancestor codes. Since 99.99% of the bits are shared, why not?

It will become clear to those practicing open-source personal genomics that genes are not destiny; they are our common wealth.