Perfect History

I realized something the other day. The Wikipedia is never CHANGED. Not really. “Changes” are always ADDITIONS to the log of all changes that have come before, including “deletions” which are really an additional pointer that moves the selected text from the front page. Nothing is actually deleted. The ultimate strength of Wikipedia comes from its perfect history. The log of state changes for a particular article reveals its veracity and credibility rather than the credentials of experts. You get different views depending on what version you care to look at. Wikipedia then is a history of state changes, rather than a state.

This never-ending-version of a “docuverse” was the original vision of Ted Nelson, the guy who coined hypertext. It is an essential element of what he wanted for the web (although he never called it that) and one of the reasons why he thinks the web as it is now is somewhat lame. One quote from Nelson:

HTML is precisely what we were trying to PREVENT— ever-breaking links, links going outward only, quotes you can’t follow to their origins, no version management, no rights management.

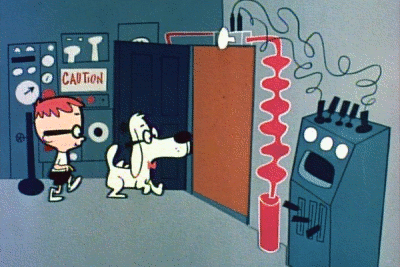

Sherman and Mr. Peabody enter the Wayback Machine

So imagine if Ted Nelson had succeeded in building Xanadu, and the entire web was run the way Wikipedia is run. Nothing is ever deleted. Everything is kept for ever. Changes are made by adding an alteration, but one could always go back to an earlier version. In one sense that is what Brewster Kahle’s Wayback Machine is. Begun in 1996 as the Internet’s only backup, it still remains so. But since it takes a snapshot of the entire web every few weeks, it also serves as a Nelsonian version tracker. Most web pages are rarely updated or modified at all, but web sites as a whole are.

The genius of Wikipedia is that they provide an elegant interface for tracking this history while viewing an item, in part because they back up all the changes themselves. There’s no built in way to do this for the web as a whole, so a continuous view of the past states of an given website is clunky. The web right now does not have perfect history.

It may be an urban legend but I’ve heard that when a blade (a computer server) dies in one of Google’s server farms, they just leave it there. The cost of finding it and swapping it out is greater than just simply adding on a new one. When we arrive at the point on our technological evolution when it becomes cheaper to save everything digital rather than throw some parts out, then we”l arrive at the state of perfect history.

In part this is what lifelogging is about. You save everything. The “now” is merely one point in an uniterrupted beam of data changes. WIthin that beam nothing vanishes. All change is addition. The past is simply a different point of view.

Perfect history changes how we think, how we view ourselves. We don’t pay enough attention to the power that our photographed past lives have on our present selves. We are reminded of episodes of our lives that we have often fully forgotten. We read messages we wrote years ago, that seem to be written by another person. Total recall shapes our identity, perhaps even constrains it. Radical growth may become more difficult, or at least require new skills of transformation — how to work around your past. Just ask someone trying to hide their MySpace pictures before a job interview. Imagine if you could never erase pictures from MySpace? Somewhere the web kept everything.

As more of our lives are recorded, stored, shared and banked in the perfect history of the One Machine, the inescapable memory will trigger powerful, and yet unappreciated forces on our souls.