Radical Optimism

[Translations: Japanese]

I am one of the most optimistic people alive. I truly believe the world is getting better in many ways each day. But last night I met someone even more radically optimistic than I, and it was a treat. Now I have room to grow!

Matt Ridley gave a talk at the Long Now Foundation’s Seminar of Long Term Thinking called Deep Optimism. Ridley is the author of a recent book, The Rational Optimist, where he makes the case that human culture was created not by language (conventional wisdom) but by the exchange of ideas. That’s a useful theory, but not upsetting. Much more provocative and powerful is Ridley’s larger thesis that progress is real, enduring, widely spread, and for the near future, unlimited. In other words, civilization as a whole is (and has been) experiencing real progress, in most dimensions, and for most people, not just the privileged. And further, this goodness shows no signs of stopping.

But it is not just material wealth that is increasing. I think Ridleys’ major contribution and insight is that we see provable progress in the soft dimensions of human life as well. As Ridley puts it:

We are becoming healthier, cleaner, smarter, kinder, happier, and more peaceful.

Not maybe, or kinda, but really. In each case he has data to support this.

I happen to agree with him, having come to similar conclusions in my own research. I wondered if Ridley had always been an optimist, and he said, no; he had been the typical worried greenie in the 1980s, and early 90s, but as a journalist he began checking sources, and he started to have doubts about the coming Armageddon. He also read Julian Simon’s book, Ultimate Resource, which gave a framework to his doubts. (Simon says that all physical resources are substitutable; when they begin to run out or become expense to produce we find substitutes. The only unsubstitutable resource — the ultimate one — is a human mind. The more minds the better.)

In his talk on Deep Optimism, Ridley presented a coherent, integrated, and astoundingly thorough case for progress in all degrees. For one easy-to-visual metric, Ridley showed how it takes less time each year to work for a constant benefit, say on hour of artificial light at night. It 1800 it took six hours of typical labor to purchase an hour’s worth of candles, so few working people did. In 1880 it took fifteen minutes of work to purchase an hour’s worth of kerosene for a lamp. In 1950 it took eight seconds of work to pay for an hour’s electricity for a light bulb. In 1997, it took only half a second — a blink — of work to light a compact fluorescent bulb for an hour.

There are a number of other radical optimists who preach the message of real progress besides Ridley, such as the late Julian Simon himself, or Ray Kurzweil, or Bjorn Lomborg. But Ridley is not as technically myopic as Kurzweil, who counts mostly technological advance; and there was no mention of a singularitian rapture. Ridley’s presentation has more hard evidence for progress in more dimensions that Simon could present. And Ridley anticipates and acknowledges known problems more than I think Lomborg does, though I find Lomborg fairly careful as well. I think Ridley has a journalist’s flair for presenting this fairly radical idea — that everything is getting better all the time — in a way that appears plausible to the average westerner. You might not believe it, but you can at least engage with the proposition.

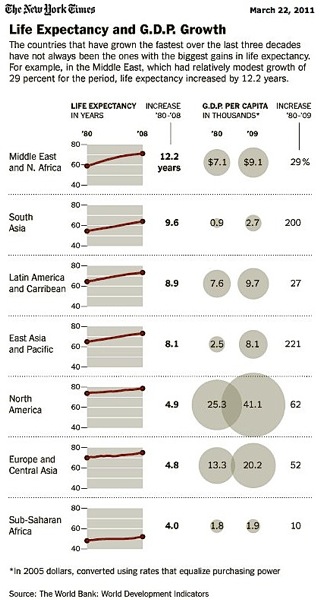

The good news about progress can be seen in many places, but we tend not to notice. Just this morning the New York Times ran a graph of improvement, based in part on the work of Charles Kenny, an economist who released a new book, Getting Better. Writing in Foreign Policy, Kenny says things have never been better and he means it:

For all its problems, the first 10 years of the 21st century were in fact humanity’s finest, a time when more people lived better, longer, more peaceful, and more prosperous lives than ever before.

Consider that in 1990, roughly half the global population lived on less than $1 a day; by 2007, the proportion had shrunk to 28 percent — and it will be lower still by the close of 2010…The proportion of the developing world’s population classified as “undernourished” fell from 34 percent in 1970 to 17 percent in 2008, even at the height of a global spike in food prices. Agricultural productivity, too, continues to climb: From 2000 to 2008, cereal yields increased at nearly twice the rate of population growth in the developing world. And though famine continues to threaten places such as Zimbabwe, hundreds of millions of people are eating more — and better — each day.

The number of armed conflicts — and their death toll — has continued to fall since the end of the Cold War. Worldwide, combat casualties fell 40 percent from 2000 to 2008. In sub-Saharan Africa, some 46,000 people died in battle in 2000. By 2008, that number had dropped to 6,000. Military expenditures as a percentage of global GDP are about half of their 1990 level. In Europe, so recently divided into two armed camps, annual military budgets fell from $744 billion in 1988 to $424 billion in 2009. The statistical record doesn’t go back far enough for us to know with absolute certainty whether this was the most peaceful decade ever in terms of violent deaths per capita, but it certainly ranks as the lowest in the last 50 years.

…If you had to choose a decade in history in which to be alive, the first of the 21st century would undoubtedly be it. More people lived lives of greater freedom, security, longevity, and wealth than ever before. And now, billions of them can tweet the good news.

There were a couple of points about radical optimism that Ridley did not mention in his talk, but did emphasis in his book, and in conversation:

1) Optimism is not based on temperament. (Ridley says he is not temperamentally optimistic.) It is a perspective that is, and should be, based on evidence and facts. It is a type of rationality that can, and should be, tested with facts. And tossed out if not true.

2) We behave better when we are optimistic. Progress depends on innovation, and innovation needs optimism; where optimism is most present, so is innovation. Hot spots of innovation in history were hot spots of optimism in otherwise pessimistic societies. What we believe about our trajectory matters.

3) A lot of pessimism is correct. If things continue as they are we are doomed. As Ridley writes: “If the world continues as it is, it will end in disaster for all humanity. If all transport depends on oil, and oil runs out, then transport will cease. If agriculture continues to depend on irrigation and aquifers are depleted, then starvation will ensue. But notice the conditional: if. The world will not continue as it is. That is the whole point of human progress, the whole message of cultural evolution.” The world will not continue as is, but will change the game.

Nonetheless many people, especially those who feel the injustices in the world, find it very difficult to remain optimistic for long. Given the three points above, the thought experiment I propose is the following: If you find the evidence offered by the radical optimists of today not convincing, what kind of evidence would convince you?

What set of 10 measurements taken over 10 years would convince you that there was progress, for the average human, either in one location or globally? Let’s pick a 10/10 metric and measure it.