Technological Superstition

[Translations: Japanese]

Superstition is alive and well in the high tech world. It is visible most prominently in our technological artifacts, some of which we treat like medieval relics. Recently, supernatural superstition has crept into American treatment of 9/11.

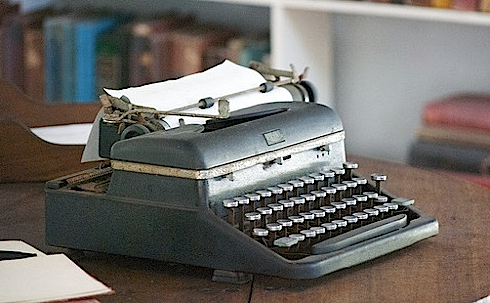

The genius of modern mass production was the machine’s ability to make cheap identical copies of any invention — unlike the uneven creations of mortal craftsmen. We figure out how to make a hunk of steel and then our factories made millions of hunks of it. We first make a typewriter prototype and then our factories made thousands, even millions, of identical clones of that typewriter.

Yet, if a famous writer used one of these identical typewriters, than that particular typewriter is endowed with an unspecified specialness. For instance Hemingway’s personal typewriters (he had more than one) are treated like relics. They are roped off, no touching them, they’ve become the object of pilgrimages, fetching more than $100,000. Yet, the venerated typewriter itself is indistinguishable from other units made on that assembly line. The only evidence that the venerated one is Hemingway’s is external — you need to trust someone’s word that this particular ONE is it. Its specialness originates in the same way as an ancient relic — because someone says so.

Is this really one of Hemingway’s typerwriters?

Relics are common in all the major religions of the world. Islam venerates the sword of Ali and the staff of Moses. In Buddhism huge pyramidal stupas were built over tiny relic shards of Buddha, including his tooth. Slivers of the cross that Jesus was crucified on were widely venerated in medieval times. These ordinarily looking pieces of wood were believed to have magical powers because there were indirectly touched by Jesus. The only evidence that those bits of wood were touched by Jesus was someone’s claim passed along by word of mouth. The wood chip itself was unremarkable — even if it was from the actual True Cross.

The logic of relics is supernatural. According to experts, the relic’s power is due to “the mystic potency emanating from the person or thing that is sacred,” a potency which in turn is transmitted to objects, and in turn transmitted to those who touch or see the object — or relic.

This relic magic operates at full throttle in the world of modern celebrity collectors. The $3 hockey puck used in the 2010 gold medal Olympics championship game later sold for $13,000 because of the unique properties it acquired during the game. The baseball that Barry Bonds hit over the fence as his record breaking 762th home run was so eagerly sought after for its special properties that it sold for $376,000. But physically the ball was indistinguishable from any MLB baseball, which anyone can buy for $17. In fact, there are no special properties of the Bond’s home run ball, so much so that there was an elaborate ritual to mark the outside balls before the game so that one could establish the provenance of the exact ball used.

Provenance is a key notion in relics and collectables. It establishes a chain of claims about previous ownership. Among believers and collectors there are often arguments about the particular provenance of a particular relic. But there is never a question about whether there really is a specialness in the artifact if its provenance is true. Collectors of manufactured items used by the famous believe that their manufactured piece — out of all the similar pieces — really does somehow contain or emanate the supernatural or mystical spirit of the famous. It is as if fame or greatness is contagious. The special power of the athlete, or movie star, or artist is transmitted through two degrees of contact.

But provenance itself does not explain why we assign any special meaning to the artifact, or to the clone. There is no non-magical reason why this clone is special just because a famous person touched it, or slept in it, or hit it. The pen used to sign the Declaration of Independence, or the guitar played Bob Dylan, or the ball hit by Barry Bonds, can only be really special if we assign these technological specimens supernatural magical contagious power.

Yet as we approach the tenth anniversary of the disasters of 9/11, there is an official campaign to assign supernatural potency to the remains of the World Trade Center. The twisted bits of steel salvaged from the site of the fallen towers are being treated as holy relics, taken on a long processions for public viewing, while the disaster site itself is being described as a “sacred place.”

Listen to these modern New Yorkers as interviewed by the Daily Mail. The reproters unabashedly use the terms “relic”:

Mark of respect: Officers from the St James New York Fire Department salute inside Hangar 17 at JFK as a piece of steel from the World Trade Center is hoisted away.

Almost 600 miles away in California, hundreds of people turned out to welcome a 9/11 relic brought back by seven members of the Brown City Fire Department.

Organised by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, the World Trade Center steel program aims to distribute the relics to firehouses and museums across America. Bill Baroni, the Port Authority’s deputy executive director, told the Boston Herald: “This is a sacred mission for this agency.”

The scenes are likely to be repeated across the country in the coming weeks, as fire departments take their turn to bring relics home.

However the rusting steel is just junk steel, the same rusty steel as any old steel beam sitting in a junk yard. It contains no discernible unique qualities. Yes, there is a long complicated and ritualistic chain of evidence to establish the provenance of these steel beams, encouraging us to believe that they somehow have special properties invisible to science. But they are indistinguishable from other bits of twisted, collapse, rusted steel. Let’s say some heartless jester swapped one of those steel beams with another one from a different collapsed building and sent the sister beam on parade around the country. Let’s say no one discovered the subversion. Would it make any difference?

To many people it would. And not just because it was a lie. But because they honestly believe that artifacts can transmit the aura of a human who uses it. In this case, the steel transmits the bravery of the firemen rescuers, and the innocence of the civilians who died. But it can also transmit cooties. They believe that wearing Hitler’s sweater would be a bad idea, while sleeping in a room (completely remodeled) that Lincoln slept in is a good idea. This is magical thinking.

There is certainly value in keeping old things. Museums that collect artifacts, like say the Computer History Museum, contain both original prototypes and arbitrary production-run units, and these contain great historical information and lessons. But it doesn’t (or shouldn’t) matter who touched or used them previously. Manufactured artifacts can’t be relics. They are all clones.

Few of us are immune from this magical thinking about artifacts. Who wouldn’t keep their father’s watch, or mother’s necklace as a family keepsake, and somehow feel cheated if someone swapped it with an identical one from the same production line? It is not the same somehow, because the very one that your dad wore on his wrist, or your mom around her neck, must in some way contain something of them. Some intangible, spiritual, ineffable quality that would be absent in another unit.

Of course, there is no difference, which is why we place so much emphasis on provenance (“it’s been in our family forever!”). In the end, a historical technological artifact is one of the reservoirs in the modern world where superstition still flows freely.