The Fifth and Sixth Discontinuity

Philosopher Bruce Mazlish claims that the eyes of science have overthrown humanity’s view of itself in a series of revelations. At each unveiling, we descend one notch. In the first removal, Copernicus dethroned our common-sense assumption that our world stood at the center of the universe. Astronomy eventually revealed, with a shock, that we were a minor tribe huddled on a small speck circling a nondescript star at the outer edge of an immense average galaxy floating among a trillion others in one small corner of the universe. The noble distinction between us and the rest of the universe was eliminated to reveal a continuous continuity of existence. Our perceived exceptionalism was demoted to the ordinary. Within the universe, we were not set apart, but dwelt in a continuum.

The second break from the exalted was launched by Darwin, who revealed that the exceptional discontinuity we perceived between ourselves and other animals or plants was equally illusionary. We are one continuous life, one evolution. Our position as humans is only one twig on a million-twigged tree, each terminal equally evolved. Within life we were not set apart, but dwelt in a continuum.

According to Mazlish the third discontinuity was located in our heads. Freud began the on-going process of overcoming the specialism we attribute to the idea of “I.” Psychology and neurology discovered that the “I” is a handy fantasy constructed to facilitate daily life, but that there is no central decider at home; rather there are many “i”s operating in our mind, and those parts are not distinguishable from our physical body, or even at times from other minds. Our own consciousness has been dethroned from central emperor to a field of cognitive tricks. Within sentience, we are not set apart, but dwell in a continuum.

We are now in the middle of dispatching the fourth discontinuity. The venerable distinction between machines and living creatures is receding so fast that it is becoming increasingly clear to everyone that a grand continuity connects the world of the made and the world of born. Nature and machine are two faces of the same extropic force. I’ve previously written a long argument in support of this continuity, and I assume its validity here on this blog. The question today is not so much whether the technium shares its roots with biological evolution, but whether it will displace its parent, or cohabit with it. Either way within the technium we, the living, are not set apart but dwell in a continuum.

But as the arc of evolution continues beyond these four continuums, what future smoothings can we expect? I propose that the next exceptionalism to be broken by science, the fifth discontinuity so to speak, is the special status we give to the physical. We feel the universe to be a place full of physical material that pushes back and presses against us. Things have weight, size, and duration. That’s what the universe is in everyday experience — the real stuff that can be really measured, felt, and sensed. Our world of matter and energy follow a set of laws to such an exacting degree that we can manipulate it to make rockets and computers. Matter’s consistent refusal to be bullied outside its own laws adds to the sense of it being “real.” Real means physical.

Information, on the other hand, lacks physicality. Unlike energy, which we can at least measure with physical instruments, a digital bit is disembodied. It weighs nothing. It takes up no space. It flows as mysteriously as a gremlin. We don’t have good measures for information. (If I make an exact copy of your song, am I increasing the amount of information in the world, or decreasing it because I am adding nothing new?) We are not yet sure if the total amount of information in the universe is conserved, nor if it is finite. Yet, we have come to see that life, even our own life, is a pattern of intangible information, rather than material form. Evolution – that great engine of creation — is a pattern of information. And mind, especially the mind, is a type of information flow. So we know that the most powerful forces in the universe (that we are aware of) are constructed of the most intangible things we can detect: bits.

There stands the discontinuity: atoms vs bits. But lately, physicists have begun to suspect that atoms are composed of information in some way we don’t understand. As legendary physicist John Wheeler puts it, “its are bits.” The deeper we inspect the interior of sub atomic particles and their quirky behavior, the more they can be explained as information flows. Many physicists expect that when we get to the bottom of how matter works that we’ll find primarily a structure of information and the absence of anything “material.” Atoms will be understood as elaborate, dynamic arrangements of intangible signals. In an article published by the American Journal of Physics, entitled “What is quantum mechanics trying to tell us” solid-state-physicist David Mermin writes “matter acts, but there are no actors behind the actions; the verbs are verbing all by themselves without a need to introduce nouns. Actions act upon other actions. [There’s] no duality between the existence of a thing and its properties: properties are all there is. Indeed: there are no things.”

As this discontinuity between the realm of the physical and the realm of the immaterial is erased, scientists have began to re-envision the laws of physics as complex algorithms of code. Energy also, is being restated in terms of information. The pulsating stars and iron planets will gradually be seen by science as wisps of intangible nothings. Organisms and technologies, including mega structures such as skyscrapers, starships, and floating cites, will be defined as structures of computation, equivalent to software. Eventually the boundary between the tangible and intangible will be completely permeable, and the special status we assign to our physicality will be seen (again) as only one station on a long continuum. Within the realm of the real, we, the physical, are not set apart, but dwell in a continuum.

On the immense journey in front of us there will undoubtedly be many more smoothings ahead beyond the five we can already see. I don’t know if it will be the sixth, seventh or nth discontinuity, but another boundary that is already being challenged is the unique place we give to the past, to causation, and to objectivity. Physical phenomenon are caused via a long chain of actions originating in the past, and we, the observers, remove ourselves from the chain of causes in order to study the phenomenon. For instance, scientists do controlled experiments and double-blind experiments so that they remain objective, removing their own observational biases from the causes they are studying. Science, which has brought us so far, clearly holds the “outside” unbiased observer to be an essential position. In fact by many definitions, science is the invention of the objective.

Further, science holds that causation must originate in the past. An event in the present is the last result of a chain of actions begun in the past. That seems logical and intuitive – as did the circling of the sun. But the weirdness of newly discovered quantum effects is rapidly breaking down the discontinuity between object and subject, past and future. With new instruments scientists can shoot quantum wave/particles through two tiny slits to measure the pattern of their arrival on a screen. Wheeler investigated exactly this experiment. True to its dual nature sometimes the wave/particle passes through the slits as a wave and sometimes it passes through them as a particle. But the particular form the wave/particle assumes as it passes through the two slits is decided upon measuring or observing the results. This is called the delayed-choice experiment because it means that the wave/particle chooses which form to pass through the slits after it has already passed through. Theoretically, if the slits were far enough away from the screen, the choice of whether the wave/particle was a wave or a particle could be delayed by billions of years after it had already happened. And this inversion of the ordinary arrow of causality is being driven by the observer.

Paul Davies suggests “the novel feature Wheeler introduced via his delayed-choice experiment was the possibility of observers today, and in the future, shaping the nature of physical reality in the past, including the far past when no observers existed.” Minds today could, in theory, shape the very foundational laws of physics in a delayed-choice action, since Wheeler claimed, “so far as we can see today, the laws of physics cannot have existed from everlasting to everlasting. They must have come into being at the big bang.” Since the laws of physics and information reside inside the cosmos, that gives mind a possible subjective role in shaping the cosmos via delayed choice. But since our minds and life are products of that cosmos, there is a necessary recursive loop. Davies writes: “Conventional science assumes a linear logical sequence: cosmos -> life -> mind. Wheeler suggested closing this chain into a loop: cosmos -> life -> mind -> cosmos.” The universe was self-synthesizing. You can start anywhere along such a recursive loop. Wheeler observed: “Physics gives rise to observer-participancy; observer-participancy gives rise to information; information gives rise to physics.” Wheeler called this subjective self-creation, “the participatory universe.”

When I asked the Piet Hut, a theoretical astrophysicist at the Institute for Advance Study at Princeton, what innovations in the practice of science he expected to see in the future, he surprised me by suggesting “the return of the subjective.” In order to get a more complete picture of reality, he said, we need to focus on the subjective. “We have painted ourselves in a corner, scientifically, by describing the whole world in objective terms, and finding less and less room for ourselves to stand on. We are now reaching the limits of a purely objective treatment. In various areas of science, from quantum mechanics to neuroscience and robotics, the pole of subjective experience can no longer be neglected.” A more recognizable thinker echoes the thought: “The histories of the Universe depend on what is being measured,” Stephen Hawking said recently, “contrary to the usual idea that the Universe has an objective, observer-independent history.”

The notion that minds in the future might evolve to the point that they could subjectively influence the laws of their own physicality is of course, only the most extreme speculation. But the delay-choice experiment is not. It happens now every time our minds observe something. I delve into the details of this frontier chiefly to illustrate how technology continues to level distinctions we once thought crucial, and how technology continues to forge a kind of unity in knowledge.

Breaking the discontinuity between the objective and subjective won’t be the last great unification either. As the technium advances, and mind expands, additional distinctions are primed to be blurred and unified. Looking ahead we can imagine that the keen distinction and superior status we assign to consciousness, versus the inert or non-unconsciousness (even if intelligent) of the rest of the material world could be unified into a continuum via technology. Likewise the discontinuity between reality and unreality (the imaginary) could likewise disappear with sufficient advanced technology.

It was not until we invented telescopes and mathematics that we could peer way past the Earth and see that it was not at the center of a revolving universe. It was not until we invented digital computation and could replicate life processes on intangible computer software that we realized that intelligence and life are not tangible. It was not until we devised sophisticated atom smashers that we began to perceive the true otherworldliness of our material world. Lasers, electron guns, charged coupler sensors, electronic chips – all these technologies made quantum mechanics visible. And once the quantum realm was visible, the paradoxes of the subjective mattered. Thus, through the medium of advanced tools, we saw a continuum where discontinuities had been seen before. In this way, as we expand the technium, upping our knowledge, we continually remove discontinuities in our perceptions.

The universe, as the sages in every religion teach us, is really one vast continuum. But to utilize knowledge of this universal continuum we need to expand our technology, which is really a way of expanding our collective mind. Technology’s long term evolution moves science – that is the interconnected, accumulated body of knowledge of all human minds – towards unity, or consilience. Consilience is a term coined in the 1840 by philosopher William Whewell and resurrected recently by E.O. Wilson to indicate the unity of knowledge. Consilience would entail, among other things, a common set of axioms that can be used to adequately explain (and predict) the phenomenon we experience in the ecology of a tundra, the interior fusion of stars, the behavior of teenage social networks, the physics of quantum computing, and the mutation of viruses. Today science is far from consilience.

In addition to uniting the principles of different scientific fields, consilience will also need to bind unrelated bodies of knowledge together, some of it ancient knowledge. Advances in communication technology and the scientific method are doing that.

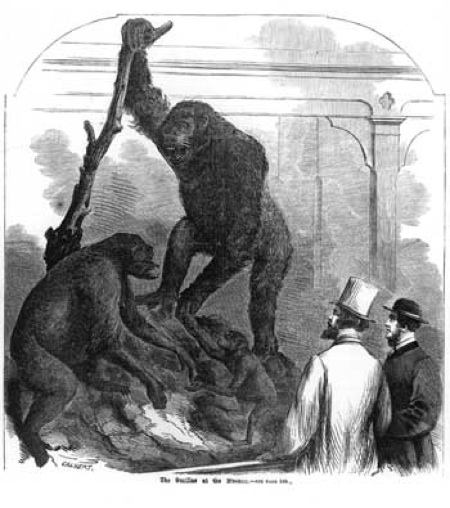

We casually talk about the “discovery of America” in 1492, or the “discovery of gorillas” in 1856, or the “discovery of vaccines” in 1796. Yet vaccines, gorillas and America were not unknown before their “discovery.” Native peoples had been living in the Americas for 10,000 years before Columbus arrived and they had explore the continent far better than any European ever could. Certain West African tribes were intimately familiar the gorilla, and many more primate species yet to be “discovered.” Dairy farmers had long been aware of the protective power of vaccines that related diseases offered, although they did not have a name for it. The same argument can be made about whole libraries worth of knowledge – herbal wisdom, traditional practices, spiritual insights – that are “discovered” by the educated but only after having been long known by native and folk peoples. These supposed “discoveries” seems imperialistic and condescending, and often are.

Engraving by Samuel Calvert of the new gorilla display at the National Museum published in The Illustrated Melbourne Post of 25 July 1865.

Yet there is one legitimate way in which we can claim that Columbus discovered America, and the French-American explorer Paul du Chaillu discovered gorillas, and Edward Jenner discovered vaccines. They “discovered” previously locally known knowledge by adding it to the growing pool of structured global knowledge. Nowadays we would call that accumulating structured knowledge science. Until du Chaillu’s adventures in Gabon any knowledge about gorillas was extremely parochial; the local tribes’ vast natural knowledge about these primates was not integrated into all that science knew about all other animals. Information about “gorillas” remained outside of the structured known. In fact, until zoologists got their hands on Paul du Chaillu’s specimens, gorillas were scientifically considered to be a mythical creature similar to Big Foot, seen only by uneducated, gullible natives. Du Chaillu’s “discovery” was actually science’s discovery. The meager anatomical information contained in the killed animals was fitted into the vetted system of zoology. Once their existence was “known,” essential information about the gorilla’s behavior and natural history could be annexed. In the same way, local farmers’ knowledge about how cowpox could inoculate against small pox remained local knowledge and was not connected to the rest of what was known about medicine. The remedy therefore remained isolated. When Jenner “discovered” the effect, he took what was known locally, and linked its effect into to medical theory and all the little science knew of infection and germs. He did not so much “discover” vaccines as much as he “linked in” vaccines. Likewise America. Columbus’s encounter put America on the map of the globe, linking it to the rest of the known world, integrating its own inherent body of knowledge into the slowly accumulating, unified body of verified knowledge. Columbus joined two large continents of knowledge into a growing global consilience.

The reason science absorbs local knowledge and not the other way around is because science is a machine we have invented to connect information. It is built to integrate new knowledge with the web of the old. If a new insight is presented with too many “facts” that don’t fit into what is already known, then the new knowledge is rejected until those facts can be explained. A new theory does not need to have every unexpected detail explained (and rarely does) but it must be woven to some satisfaction into the established order. Every strand of conjecture, assumption, observation is subject to scrutiny, testing, skepticism and verification. Piece by piece consilience is built.

In this way consilience is a type of technology, expanded by technology. Unified knowledge is constructed by the mechanics of duplication, printing, postal networks, libraries, indexing, catalogs, citations, tagging, cross-referencing, bibliographies, keyword search, annotation, peer-review, and hyperlinking. Each epistemic invention expands the web of verifiable facts and links one bit of knowledge to another. Knowledge is thus a network phenomenon, with each fact a node. We say knowledge increases not only when the number of facts increases, but more so when the number and strength of relationships between facts increases. It is the relatedness that gives knowledge its power. Our understanding of gorillas deepens and becomes more useful as their behavior is compared to, indexed with, aligned into, and related to the behavior of other primates. Our consilience is expanded as their anatomy is related to other animals, as their evolution is integrated into the tree of life, as their ecology is connected to the other animals co-evolving with them, as their existence is noted by many kinds of observers, until the facts of gorillahood are woven into the encyclopedia of knowledge in thousands of criss-crossing and self-checking directions. Each strand of enlightenment enhances not only the facts of gorillas, but also the strength of the whole cloth of human knowledge.

And as in any networked system, the larger the pool of nodes that are being linked up in the network, the more powerful it is. Doubling the number of nodes more than doubles its value. To a rough approximation, as the nodes of a network increase linearly, its value grows exponentially. This exponential growth in power means that one larger network is vastly more valuable than two smaller networks with the same total number of members. Let’s say that community “A” has integrated 10 facts into its pool of knowledge. If each fact is related in some way to the others, then the collective knowledge swells exponentially by 10^2, or 100 assertions. At the same time on another part of the planet, community “B” has integrated a different set of 10 facts with a similar value. If a Columbus or encyclopedist were able to combine those two pools of knowledge, the 10 A nodes with the 10 B nodes, and then interrelate those 20 facts into a single integrated web of knowledge, the value of that unified pool is twice the value (400, or 20^2) compared to the sum of the two isolated pools (2 x 100). The mathematics favors a single seamless carpet of knowledge over separate disjoined knowledge. When a self-contained patch of information can be woven into a global consilience it increases the value of all parts.

Today there remain many unconnected pools of knowledge. The unique wealth of traditional wisdom won by indigenous tribes in their long intimate embrace of their natural environment is very difficult (if not impossible) to move out of their native context. Within their system, their sharp knowledge is tightly woven, but it is disconnected from the rest of what we collectively know. A lot of shamanic knowledge is similar. Currently science has no way to accept these strands of spiritual information and weave them into the current consilience, and so their truth remains “undiscovered.” Certain fringe sciences, such as ESP, are kept on the fringe because their findings, coherent in their own framework, don’t fit into the larger pattern of the known.

The perceived divisions between types of knowledge, between levels of knowing, and between distinctions in our own standing in the universe are all being steadily leveled by the advance of the technium. Bit by bit technology illuminates the continuum that connects everything. In the usual self-amplifying circle of upcreation, each advance in knowledge also facilitates new inventions, unleashing yet more revealing technology. While our system of science can increase ignorance faster than it can increase knowledge (see the Expansion of Ignorance), new instruments amplify our ways of seeing and powers of systemic thinking. New tools fatten our collective memory and deepen our understanding. Just as the technium is currently in the process of connecting all humans to each other (via the internet), and all devices to each other (ditto), it is also in the process of connecting each idea to all other ideas, so that there is a one unified body of knowledge.

Over the long haul, as the technium becomes more complex, accelerated and sentient, technology tends toward consilience.