The Gravity of Paper

The other day I visited an astounding library of forgotten paper. Located in San Francisco, in a large utilitarian room in a drab building, the Prelinger Library is an electrifying planetary power spot. Sparks of inspiration, adoration, amazement, and love issue from between the towering stacks of paper and tapes. While I am busily migrating as fast as I can to ebooks and screen publishing, a visit to this temple of paper gave me many second thoughts. This was serious paper power.

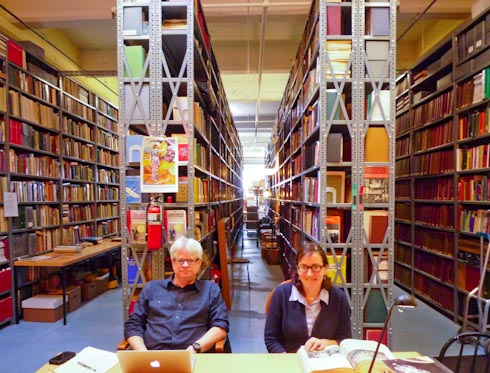

When I walked through the front door of the library unannounced I saw this: two folks sitting at a table, one reading a lap top and one reading a huge old book filled with engravings. The guy on the left is Rick Prelinger and the gal on the right is his partner Megan Shaw Prelinger. Together they have amassed this ark of books, video and ephemera, focusing on the role of landscape and technology in the 20th century. The library is “appropriation friendly.” They encourage visitors to scan books, photograph pages, share, quote, post, twitter, alter, remix, and use the content as much as possible. (The library is open to the public every Wednesday and other times by appointment.)

For many years Rick has been collecting boring corporation and government educational films, zines, phone books, self-published tracks, technical monographs, trade publications, and all kinds of revealing material that is normally thrown away and not collected by proper libraries. At the same time, poor public libraries face cuts, so they have been tossing out valuable collections of Communications Monthly from the 1930s, or Electric Railway Review, and these the Prelingers have saved in their library. This has yielded a treasure house of intimate accounts of what was really happening in the last century.

I spent an hour in orgasmic glee dipping into the stacks of old engineering magazines from the 50s, filled with astounding advertisements. There were endless volumes of US trade mark books, stuff to the brim with tens of thousands of brilliant logos and graphics and brands from the turn of the century — all forgotten but still potent today. There were the plans and worries and dreams of the folks building the interstate highway system, in glorious details in dozens of journals. There were found home videos about life in the suburbs. Everywhere I turned, something vibrant rose to life.

So why was this different than getting lost in Google Books, or the web itself?

In some ways it is very similar and offers a similar serendipity. But stacks of paper offer several user experiences that are superior to online browsing.

First, the speed of browsing in person is so much faster than browsing through files online that it really should be called something else because it feels like a different experience. In the stacks it is closer to exploring. I can pick up a bound book and drive through it tens of times faster, with more accuracy, and better retention. It is partially a matter of a faster “refresh rate” with paper books — one can flip pagers faster than clicking — and partly the ability to navigate in 3D, seeing where I am in the whole between the beginning and end.

Secondly, the speed of exploring between books in the library is much faster than browsing online. And despite the recommendations offered by Google (or Amazon), the quality of gems one finds in exploring the adjacent shelf in a library does not always match those found by algorithm (though that is getting better all the time.) There is a fluidity near to dance in soaring from one book to another — especially when nearly every volume in this highly select library is a gem.

Thirdly, the tactile dimension of the screen is yet not on par with the often large pages (much bigger than your iPad or laptop screen), the very thick books, the smooth papers and crisp inks. You can SEE. And see without tiring.

Fourth, most of this stuff is not digital yet. It is still only found on paper.

Finally, and I think most importantly, this is a collection, a library, that has been seriously, intelligently, brilliantly curated, so you get the best. Every touch is rewarded. That keeps you going.

I didn’t want to leave. Entering into these stacks of old magazines, and old time adverts, and newsletters from proto-hackers, and the earliest nerds before they were cool, and the annals of progress as written by bureaucrats, and the photographic evidence of rapid change in our own neighborhoods — how could I turn away? It was intoxicating. There was some might gravity in these paper artifacts that pulled me toward them, and even now sitting 8 miles away in my office I can still feel the pull of these remarkable documents. Everyone of them came close to being dumped, burned or recycled. But here they are in this ark, preserved for sharing.

Someday, if the Prelinger’s dreams come true, anyone WILL be able to browse this extraordinary library from a screen in Nepal, or Libya, or Peru. (Thus the laptop next to the book on the front desk.) But nonetheless, it will still be worth a pilgrimage to the stacks, just to tap into its unmediated browsing power. And when you come, bring a gift for the stacks of a view of the technium that almost got thrown away.