The Maes-Garreau Point

[Translations: Japanese]

Forecasts of future events are heavily influenced by present circumstances. That’s why predictions are usually wrong. It’s hard to transcend current assumptions. Over time, these assumptions erode, which leads to surprise. Everybody “knew” that people won’t work for free, and if they did that it would not be quality work. So the common assumption that a reliable encyclopedia could not be constructed upon volunteer labor blinded us to the total surprise of a Wikipedia.

The present-bound nature of predictions is not news. But forecasts may be more bound to the personal life of the predictor than first appears. Here is a story. Pattie Maes, a researcher at the MIT Media Lab noticed something odd about her colleagues. A subset of them were very interested in downloading their brains into silicon machines. Should they be able to do this, they believed, they would achieve a kind of existential immortality. Presumably, once downloaded, their souls could easily be migrated from one hardware upgrade to the next. So on, ad infinitum.

The technology to work this miracle seemed far away, but all agreed that once someone designed the first super-human artificial intelligence, this AI could be convinced to develop the technology to download a human mind immediately. This moment was christened the Singularity because what happen afterwards seemed impossible to even imagine. But, if one could make it to the Singularity, that is, if one could live until the time when a super-human mind was operational, then one could be downloaded into immortality. You were home-free for eternity. The trick was to stay alive until this bridge was crossed.

All the guys who were counting on this were, well, … guys. Pattie saw this a very male desire. She hypothesized that “women may have less of a desire to reach immortality via living in the form of silicon, because women go through pregnancy & birth and as such experience a more biological method of ‘downloading/renewal/making of a copy of oneself.’ Of course men are involved in having children, but for a woman it is a more concrete, physical experience, and as such maybe more real.”

Nonetheless, her colleagues really, seriously expected this bridge to immortality to appear soon. How soon? Well, curiously, the dates they predicted for the Singularity seem to cluster right before the years they were expected to die. Isn’t that a coincidence?

This idea is nicely summarized by this cartoon (found here):

In 1993 Maes gave a talk at Ars Electronic in Linz, Austria called “Why Immortality Is a Dead Idea.” Rodney Brooks, one of her male colleagues, summarized the talk in his book Flesh and Machines:

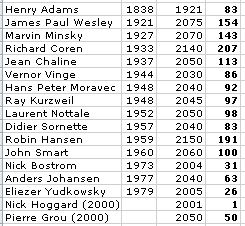

[Maes] took as many people as she could find who had publicly predicted downloading of consciousness into silicon, and plotted the dates of their predictions, along with when they themselves would turn seventy years old. Not too surprisingly, the years matched up for each of them. Three score and ten years from their individual births, technology would be ripe for them to download their consciousnesses into a computer. Just in the nick of time! They were each, in their own minds, going to be remarkably lucky, to be in just the right place at the right time.

Maes did not write up her talk or keep the data. And in the intervening 14 years, many more guys have made public their predictions of when they think the Singularity will appear. So, with the help of a researcher, I have gathered all the predictions of the coming Singularity I can find, with the birthdates of the predictors, and charted their correspondence.

You will not be surprised to find that in half of the cases, particularly those within the last 50 years, the Singularity is expected to happen before they die – assuming they live to be 100. Joel Garreau, a journalist who reported on the cultural and almost religious beliefs surrounding the Singularity in his book Radical Evolution, noticed the same hope that Maes did. But Garreau widen the reach of this desire to other technologies. He suggested that when people start to imagine technologies which seem plausibly achievable, they tend to place them in the near future – within reach of their own lifespan.

I think they are onto something. I have formalized their hunches into a general hypothesis I christen in honor of them.

The latest possible date a prediction can come true and still remain in the lifetime of the person making it is defined as The Maes-Garreau Point. The period equals to n-1 of the person’s life expectancy.

This suggests a law:

Maes-Garreau Law: Most favorable predictions about future technology will fall within the Maes-Garreau Point.

I haven’t researched a lot of other predictions to confirm this general law, but its validity is disadvantaged by one fact. Singularity or not, it has become very hard to imagine what life will be like after we are dead. The rate of change appears to accelerate, and so the next lifetime promises to be unlike our time, maybe even unimaginable. Naturally, then, when we forecast the future, we will picture something we can personally imagine, and that will thus tend to cast it within range of our own lives.

In other words we all carry around our own personal mini-singularity, which will happen when we die. It used to be that we could not imagine our existence after our death; now we cannot imagine the details of anyone’s existence after our death. Beyond this personal singularity, life is unknowable. We tend to place our imaginations and predictions before our own Maes-Garreau Point.

Because the official “Future” — that far away utopia — must reside in the territory of the unimaginable, the official “future” of a society should always be at least one Maes-Garreau Point away. That means the official future should begin after the average lifespan of an individual in that society.

The Baby Boom generation (a world-wide phenomenon) has an expected life span of about 80 years. Born about 1950, most baby boomers should be dead by 2040. However all kinds of other powerful things are expected to happen by 2040. China’s economy is due to overtake the US in 2040. 2040 is the average date when the Singularity is supposed to happen. 2040 is when we expect Moore’s Law to reach the computational power of a human on a desk top. 2040 is also about when the population of the world is supposed to peak once and for all, and environmental pressure decrease. This grand convergence of global scale disruptors are all scheduled to appear – no surprise – at exactly the date of this generation’s Maes-Garreau Point: 2040.

If, as many hope, our longevity increases with each year, maybe we can extend our lives way past 80. As we do, our Maes-Garreau Point slips further into the future. The hope of the gentleman in the chart – and my hope too – is that we can extend our personal mini-singularity past the grand Singularity, and live forever.