The Possiplex

The guy who invented hypertext and hyperlinks, Ted Nelson, has self-published his autobiography, Possiplex . Say what you want about Ted, but he has a remarkable ability to coin words. Possiplex is his term for that larger web in cyberspace, since he thinks the world wide web is a disaster.

Ted Nelson’s autobiography is a direct response to an profile I commission of him almost 20 years when I was editing Wired. For 20 years Ted has believe that Gary Wolf’s amazing story about him has hijacked the true story, Ted’s own story, and his autobiography is that story. As Nelson writes in the “aforethough”:

Everybody wants to tell their story; I have special reasons. I have a unique place in history and I want to claim it. I also want to clear the air, substituting the true story for myth and misunderstandings about my life and work.

This is not a modest book. Modesty is for those who are after the Nobel, and that chance (if any) is long past. This is what I want known long after. Like Marco Polo and Tesla in their autobiographies, I am crazed for people to know my real story. now at last we could break free.

It’s hard to describe what reading Ted Nelson is like. His ideas explode, slip away, erupt into sudden brilliance, fade into nonsense, awaken insight, divert to irrelavant tangents again and again, get intensely geeky, and then soar into poetry. One has the impression of watching a thought richocet around a mind, looking for order. In his infamous article, The Curse of Xanadu, so hated by Ted, Gary suggests that Nelson invented hyperlinking and the web as an antidote to his own self-diagnosed attention deficit disorder, a way to keep track of things in his own mind.

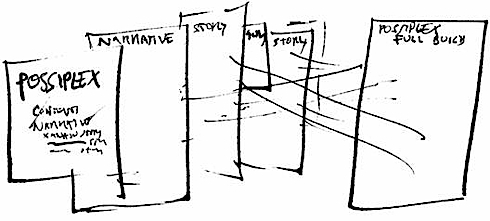

Unprepared readers may find Nelson’s style either delightful or frustrating. Personally I enjoy Nelson’s brilliance — in small doses. Ted has always self-published his own books, and that includes their drawings, diagrams and layout. They are kinetic, visual, hyperactive. They are very webby. And slightly allergic to commercial publishers. Nelson writes:

I believed passionately in self-publishing, and still do. The publishing industry has always catered to, and been run by, the shallow, conventional, pompous and smug, with attitudes generally obtuse and behind the times. I wanted to free authors to publish on an even footing with big companies. My great-grandfather self-published his poetry. My grandmother self-published her poetry, novels and drawings. I had self-published in college and intended to go on doing so, but this would be the real way to do it. (I have generally self-published out of choice [various bitter anecdotes omitted]. If self-publishing was good enough for William Blake, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Richard Burton the explorer* and T.E. Lawrence, it’s good enough for me. The revenue is a lot less but I there’s no need to fight with editors, to compromise or dumb down.)

Ted Nelson is a humanist through and through. He’s geeky by ethnicity but not temperment. He invents technology because he wants to avoid it. He’s a bigger than life persona, an actor in love with words, an artist teasing us with truth. I love the words he has gifted us: transclusion, intertwingle, fangles, populitism, dildonics, micropayment, docuverse, technoid, scientific visualization, among others.

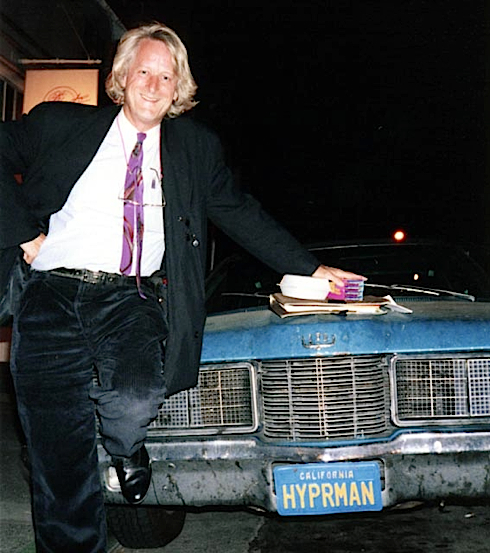

I am a great fan of Ted, and deeply respect him even though he hates me for publishing that profile of him, which most ordinary readers think shows him to be a hero of sorts. Here is a snap I took of him years ago when we were still friends.

Do read his books. Here are a few excerpts from his long-promised autobiography.

* Pop read many books to us, including Just So Stories, Swiss Family Robinson, and a number of the Doctor Dolittle books. And my favorite early book, Paddle-to-the-Sea, by Holling… My earliest visions of hypertext and hypermedia, in the 1960s, were closely related to Paddle-to-the-Sea. Each of its chapters has a text, a painting, an ink drawing, and a map. The reader (or the read-to) unites these in the mind, learning to connect different aspects of sight and story.

* In that first year at Harvard, 1960-1, I took a computer course, and my world exploded. Freed Bales (he didn’t use the “Robert” socially) was a most amiable and pleasant psychologist in my Soc Rel department. His long-term research included a gut course that could be taken any number of times by undergraduates and grad students alike, in which they argued about interpersonal issues at any level of inanity they chose. Meanwhile, behind one-way glass, Bales’ research assistants were taking down and coding everything that happened.

Bales made the most trenchant remark on computers I ever heard.

‘The computer is the greatest projective system* ever created’, Bales said to me. Meaning that anyone looking at the computer would think they were seeing reality, but would see something projected from their own mind. *A projective system is something which, like a Rorschach test, invites people to project on it their own personalities and ideas, often unwittingly.

* I could not have imagined that two decades later later that others would imitate paper, or that the imitation of paper would become the center of the computer world!

* I needed a word for all these ideas.

(It did not come soon. Sometime in spring 1961, I think, I came up with splandremics. By which I meant– • the design of presentational systems and media • the design of interactive settings and objects • establishing conventions and overall frameworks for these designs

The place where you would work–your screen setup and computer, or whatever else it would contain–I wanted to call a splandrome. Nobody could imagine what I was talking about.

* I had felt a conflict between being an idealist and making money. (Not an uncommon conflict for a young man.) No more. This would make the world a far better place and make me tons of money on the way. Here was a single path to everything I believed in and wanted. What more worthy goal could a brash young man choose, than to rebuild civilization anew?

I figured that programming the system, deploying it and revolutionizing the world would take about two years. I was impatient to get done with that. Then I could get back to movie-making, and I would be able to finance my movies myself without having to deal with backers.

There has never been any other plan.

I wanted to be the Gutenberg of this new medium that only I imagined. And the Griffith and the Disney. Especially the Gutenberg.

Little did I know that Gutenberg had gone bankrupt.

* [The book continues for fifty more years.]

This last sentence is the last sentence in the free first chapter that Nelson posted on his website. I am sure he is not kidding.

I think I have all of Ted’s books. While his original two are justly famous — Literary Machines and Computer Lib – few noticed his last self-published tome, Geeks Bearing Gifts, available from Lulu and Amazon, as is this new one. As usual it was filled with bombastic claims, arrogant brilliance, weird rants, sorry complaints, and utter genius. Pure Ted. It’s a pretty good bet this one will deliver more of the same.