The Speed of Information

The fastest increasing quantity on this planet is the amount of information we are generating. It is (and has been) expanding faster than anything else we create or can measure over the scale of decades. That means that at the very edge of change, where change changes the most, information is leading. Information is accumulating faster than any material or artifact in this world, faster than any by-product of our activities. The rate of growth in information may even be faster than any biological growth at the same scale.

Recently two economists at UC Berkeley calculated our total global information production for one year. In their study “How much information?” researchers Hal Varian and Peter Lyman measured the total production of all information channels in the world for two different years, 2000 and 2003. Their totals include the information found on all analog media such as paper, film, and tape, as well as in all digital media such as hard disks and chips, and through all bandwidth such as TV, radio and telecommunications. Their tally focused on unique information, rather than just bits, since a duplicate of a song (or photo, or database) does not contain any real additional information. Therefore they counted a newly recorded song as new information, but not all the copies of that song, even though those additional copies would require storage space and transmission bandwidth.

Varian and Lyman estimate that the total production of new information in 2000 reached 1.5 exabytes. They explain that is about 37,000 times as much information as is in the entire holdings Library of Congress. For one year! Three years later the annual total yielded 3.5 exabytes. That yields a 66% rate of growth in information per year. This rate hardly seems astronomical compared to say the 600% increase in iPods shipped last year. But that kind of iPod burst is not sustainable over decades, while the growth of information has been steadily increasing for at least a century.

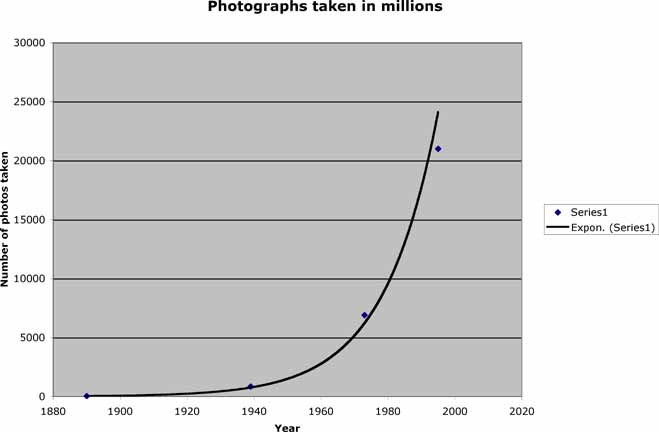

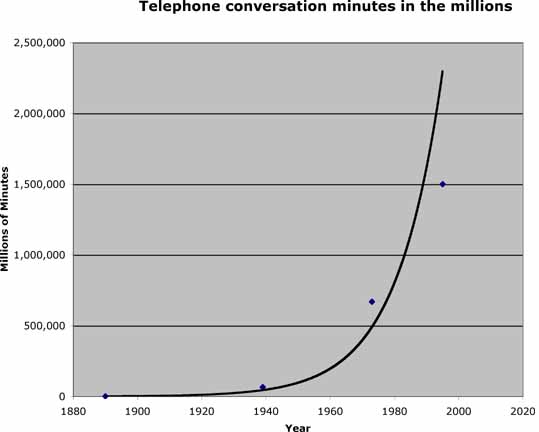

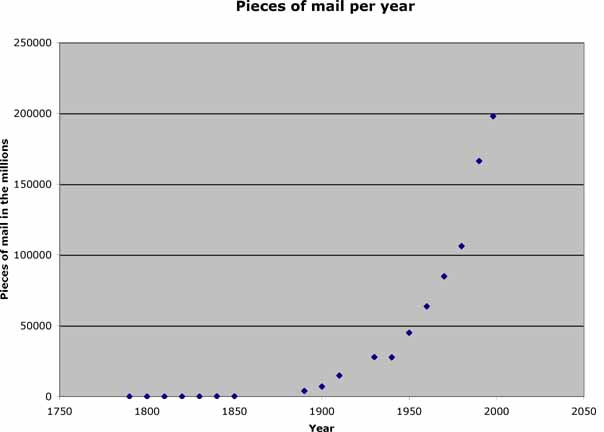

For instance, the quantity of scientific knowledge, as measured by the number of scientific papers, has been doubling approximately every 15 years since 1900. If we measure simply the number of journals published we find that they have been exponentially rising since the 1700s, when science began. The amount of mail sent over the US postal system has been doubling every 20 years for 80 years. The number of photographic images (information) taken on film has steadily risen exponentially since the medium was invented in 1850s. The number of telephone call minutes likewise follows an exponential curve for over 100 years. These are just four small rivers of information that keep accelerating their flow. I am aware of no stream of information that is lessening.

There are several curious consequences from this steady explosion. First, there appears to be no efficiency with information. Over centuries we can map a steady progress in creating more stuff using less time, less money, and less material – that’s called productivity. By almost any measure in any industry, productivity is and has been steadily, measurably increasing. It’s what we think of as progress. But we achieve gains in efficiency and productivity by using more information. Whatever we produce in greater quantities — even if it is cement — requires and generates a corresponding increase amount of information to organize its production and sale. Each additional ton of cement would necessitate a new record at the manufacturer, the distributor, the customer, and so on for k times throughout its chain of being. The rate of information expansion would also increase k times and would thus be proportional (no more, no less) to the rate of production. Information would not grow any faster than the fastest growth of production.

But that’s only part of the story. Over time (measured in decades) there are actually k + 1 records per activity. This increase is due to the fact that whatever we produce in greater qualities also generates new information since value is added to materials and services by adding information to the process. Let’s return to the supernova of new iPods. Before the iPod there were few databases of “tracks” (vs. albums), few databases of songs sold online, and of course few databases of iPod-like units. Most significantly there are millions of new playlists which had not existed before, and hundreds of new methods of sharing, cataloging, indexing and developing the information about playlists. This is what Hal Varian calls the “democratization of data.” Ordinary consumption by consumers is actually producing as much information as the traditional sources of production.

All of these additional record databases were added to the k number of existing music databases. The growth of these additional records certainly grows faster than the iPods because we (consumers and producers) are always inventing new ideas about them and their value.

Secondly, we generate far more information than we capture and record. This unaccounted-for information is “wild” information; it is also unmonetized growth. We can sense it in the blogosphere and social networking domain, where much information is not made explicit. In our ordinary lives we generate information by all that we do – conversation, choices, humdrum activities — and little of this makes it way onto wires. This expanding territory of “wild” information runs ahead of the economy. The effort of business is, in fact, to “tame” this expansion by formally monetizing it. But the wild is growing faster than tamed.

The long-term trend is simple: the information about and from a process will grow faster than the process itself. Productivity generates excess information, and so as we progress, information will grow faster than whatever else is being produced.

We can approach the question from the other side. If it isn’t information, then what other measurable quantity is growing fastest in the world over the span of decades? What is growing faster than 66% for decades — that is not information based? Economists peg physical production as growing at 3% a year in advanced countries, and maybe 7% a year in superstars like China. That means that information grows 10 times as rapidly as physical production.

It is hard to imagine anything else in the world that could possibly grow that fast. Even with information it is hard to imagine how it could continue to expand at that yearly rate, since humans are not reproducing at that rate. How could information continue to accumulate at 66% per year for decades more? With machines. Most humans can consume more information in an hour than they generate (so much easier to watch a video than to make one) but machines can generate more information than they consume day and night. Embedded sensors, cameras with no human eyes, bots on the web, computer-run systems all generate enormous oceans of data outside of human view. It is plausible to image the global sphere of information expanding exponentially as data generation becomes mechanical.

My conclusion: On the time scale of decades and longer, information is the fastest growing thing on this planet.