The World Without Technology

I remember the smoke the most. That pungent smell permeating the camps of tribal people. Everything they touch is infused with the lingering perfume of smoke — their food, shelter, tools, and art. Everything. Even the skin of the youngest tribal child emits smokiness when they pass by. I can hold a memento from my visits decades later and still get a whiff of that primeval scent. Anywhere in the world, no matter the tribe, steady wafts of smoke drift in from the central fire. If things are done properly, the flame never goes out. It smolders to roast bits of meat, and its embers warm bodies at night. The fire’s ever-billowing clouds of smoke dry out sleeping mats overhead, preserve hanging strips of meat, and drive away bugs at night. Fire is a universal tool, good for so many things, and it leaves an indelible mark of smoke on a society with scant other technology.

Besides the smoke I remember the immediacy of experience that opens up when the mediation of technology is removed in a rough camp. Living close to the land as hunter-gatherers do, I got colder often, hotter more frequently, soaking wet a lot, bitten by insects faster, more synchronized to rhythm of the day and seasons. Time seemed abundant. I was shocked at how quickly I could dump the cloud of technology in my modern life for a cloud of smoke.

But I was only visiting. Living in a world without technology was a refreshing vacation, but the idea of spending my whole life there was, and is, unappealing. Like you, or almost anyone else with a job today, I could sell my car this morning and with the sale proceeds instantly buy a plane ticket to a remote point on earth in the afternoon. A string of very bumpy bus rides from the airport would take me to a drop-off where within a day or two of hiking I could settle in with a technologically simple tribe. I could choose a hundred sanctuaries of hunter-gatherer tribes that still quietly thrive all around the world. At first a visitor would be completely useless, but within three months even a novice could at least pull their own weight and survive. No electricity, no woven clothes, no money, no farm crops, no media of any type — only a handful of hand-made tools. Every adult living on earth today has the resources to relocate to such a world in less than 48 hours. But no one does.

The gravity of technology holds us where we are. We accept our attachment. But to really appreciate the effects of technology – both its virtues and costs — we need to examine the world of humans before technology. What were our lives like without inventions? For that we need to peek back into the Paleolithic era when technology was scarce and humans lived primarily surrounded by things they did not make. We can also examine the remaining contemporary hunter-gatherer tribes still living close to nature to measure what, if anything, they gain from the small amount of technology they use.

The problem with this line of questioning is that technology predated our humanness. Many other animals used tools millions of years before humans. Chimpanzees made (and of course still make) hunting tools from thin sticks to extract termites from mounds, or slam rocks to break nuts. Even termites themselves construct vast towering shells of mud for their homes. Ants herd aphids and farm fungi in gardens. Birds weave elaborate twiggy fabrics for their nests. The strategy of bending the environment to use as if it were part of your body is a billion year old trick at least.

Our humanoid ancestors first chipped stone scrapers 2.5 million years ago to give themselves claws. By about 250,000 years ago they devised crude techniques for cooking, or pre-digesting, with fire. Technology-assisted hunting, versus tool-free scavenging, is equally old. Archeologists found a stone point jammed into the vertebra of a horse and a wooden spear embedded in a 100,000 year old red deer skeleton. This pattern of tool use has only accelerated in the years since.

To put it another way, no human tribe has been without at least a few knives of bone, sharpened sticks, or a stone hammer. There is no such thing as a total tool-free humanity. Long before we became the conscious beings we are now we were people of the tool. Hunters increased the power of a spear by launching it from a long swinging stick (the atlatl) which literally extended their arm. In fact all tools are extensions of our biological body, just as the artifact of a beehive is an extension of a bee. Neither honeycomb nor queen bee can exist alone. Same for us. Evolutionarily we’ve survived as a species because we’ve made tools, and we’d perish as a species without at least some of our inventions.

Although strictly speaking simple tools are a type of technology made by one person, we tend to think of technology as something much more complicated. But in fact technology is anything designed by a mind. Technology includes not only nuclear reactors and genetically modified crops, but also bows and arrows, hide tanning techniques, fire starters, and domesticated crops. Technology also includes intangible inventions such as calendars, mathematics, software, law, and writing, as these too derive from our heads. But technology also must include birds’ nests and beaver dams since these too are the work of brains.

All technology, both the chimp’s termite fishing spear and the human’s fishing spear, the beaver’s dam and the human’s dam, the warbler’s hanging basket and the human’s hanging basket, the leafcutter ant’s garden and the human’s garden, are all fundamentally natural. We tend to isolate human-made technology from nature, even to the point of thinking of it as anti-nature, only because it has grown to rival the impact and power of its home. But in its origins and fundamentals a tool is as natural as our life.

Tools and bigger brains mark the beginning of a distinctly human line in evolution 2.5 million years ago. The first simple stone tools appeared in the same archeological moment that brains of the hominins who made them began to enlarge toward their current size. Thus hominins arrived on earth with rough chipped stone scrapers and cutters in hand. About a million years ago these large-brain, tool-wielding hominins drifted out of Africa and settle into southern Europe, where they evolved into the Neanderthal (with even bigger brains), and further into east Asia, where they evolved into Homo erectus (also bigger brained). Over the next several millions of years, all three hominin lines evolved, but the ones who remained in Africa evolved into the human form we see in ourselves. The exact time these proto-humans became fully modern humans is of course debated. Some say 200,000 years ago but the undisputed latest date is 100,000 years ago. By 100,000 years ago humans crossed the threshold where they are indistinguishable from us outwardly. We would not notice anything amiss if one of them were to stroll alongside of us on the beach. However, their tools and most of their behavior were indistinguishable from their relatives the Neanderthals in Europe and Erectus in Asia.

For the next 50 millennia not much changed. The anatomy of African human skeletons remained constant over this time. Neither did their tools change much. Early humans employed rough-and-ready lumps of rock with sharpened edges to cut, poke, drill, or spear. But these hand-held tools were unspecialized, and did not vary by location or time. No matter where or when in this period (called the Mesolithic) a hominin picked up one of these tools it would resemble one made tens of thousands of miles away or tens of thousands of years apart, whether in the hands of Neanderthal, Erectus or Homo sapiens. Hominins simply lacked innovation. As Jared Diamond put it, “Despite their large brains, something was missing.”

Then about 50,000 years ago something amazing happened. While the bodies of early humans in Africa remained unchanged, their genes and minds shifted noticeably. For the first time hominins were full of ideas and innovation. These newly vitalized modern humans, which we now call Sapiens, charged into new regions beyond their ancestral homes in eastern Africa. They fanned out from the grasslands and in a relatively brief burst exploded from a few tens of thousands in Africa to an estimated 8 million worldwide just before the dawn of agriculture 10,000 years ago.

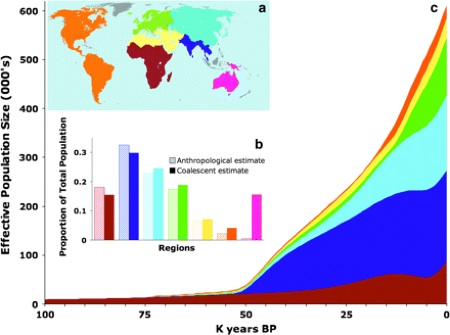

A simulation of the 50,000 year BP population explosion in prehistory. From Atkinson.

The speed at which Sapiens marched across the planet and settled every continent (except Antarctica) is astounding. In 5,000 years they overtook Europe. In another 15,000 they reached edges of Asia. Once tribes of Sapiens crossed the land bridge from Eurasia into what is now Alaska, it took them only a few thousand years to fill the whole of the New World. Sapiens increased so relentlessly that for the next 38,000 years they expanded their occupation at the average rate of one mile per year. Sapiens kept pushing until they reached the furthest they could go: land’s end at the tip of South America. Less than 1,500 generations after their “great leap forward” in Africa, Homo sapiens had become the most widely distributed species in Earth’s history, inhabiting every type of biome and every watershed on the planet. Sapiens were the most invasive alien species ever.

Today the breadth of Sapien occupation exceeds that of any other macro-species we know of; no other visible species occupies more niches, geographically and biological, than Homo sapiens. Sapien’s overtake was always rapid. Jared Diamond notes that “after the ancestors of the Maori reached New Zealand” carrying only a few tools, “it apparently took them barely a century to discover all worthwhile stone sources; only a few more centuries to kill every last moa in some of the world’s most rugged terrain.” This sudden global expansion following millennia of steady sustainability is due to only one thing: technology and innovation.

As Sapiens expanded in range they remade animal horns and tusks into thrusters and knives, cleverly turning the animals’ own weapons against them. They sculpted figurines, the first art, and the first jewelry, beads cut from shells, at this threshold 50,000 years ago. While humans had long used fire, the first hearths and shelter structures were invented about this time. Trade of scarce shells, chert and flint rock began. At approximately the same time Sapiens invented fishing hooks and nets, and needles for sewing hides into clothes. They left behind the remains of tailored hides in graves. In fact, graves with deliberately interred burial goods were invented at this time. Sometimes recovered beads and ornaments in the burial site would trace the borders of the long-gone garments. A few bits of pottery from that time have the imprint of woven net and loose fabrics on them. In the same period Sapiens also invented animal traps. Their garbage reveals heaps of skeletons of small furred animals without their feet; Trappers today still skin small animals the same way by keeping the feet with the skin. On walls artists painted humans wearing parkas shooting animals with arrows or spears. Significantly, unlike Neanderthal and Erectus’s crude creations, these tools varied in small stylistic and technological ways place by place. Sapiens had begun innovating.

The Sapien mind’s ability to make warm clothes opened up the artic regions, and the invention of fishing gear opened up the coasts and rivers of the world, particularly in the tropics, where large game was scarce. While Sapien’s innovation allowed them to prosper in new climates, the cold and its unique ecology especially drove innovation. More complex “technological units” are needed (or have been invented) by historical hunter-gatherer tribes the higher the latitude of their homes. Hunting oceanic sea mammals in artic climes took significantly more sophisticated gear that fishing salmon in a river. The ability of Sapiens to rapidly adapt tools allowed them to rapidly adapt to new ecological niches, at a much faster rate than genetic evolution could ever allow.

During their quick global takeover, Sapiens displaced (with or without interbreeding) the several other co-inhabiting hominin species on earth, including their cousins the Neanderthal. The Neanderthals were never abundant and may have only numbered 18,000 individuals at once. After dominating Europe for hundreds of thousands of years as the sole humanoid, the Neanderthals vanished in less than 100 generations after the tool-carrying Sapiens arrived. That is a blink in history. As anthropologist Richard Klein says, “this displacement occurred almost instantaneously from a geologic perspective. There were no intermediates in the archeological record. The Neanderthals were there one day, and the Cro-Magnons [Sapiens] were there the next.” The Sapien layer was always on top, and never the reverse. It was not even necessary that the Sapiens slaughter the Neanderthals. Demographers have calculated that as little as a 4 percent difference in reproductive effectiveness (a reasonable expectation given Sapien’s ability to bring home more kinds of meat), could eclipse the lesser breeding species in a few thousands years. The speed of this several thousand-year extinction was without precedent in natural evolution. Sadly it was only the first rapid species extinction to be caused by humans.

It should have been clear to Neanderthal, as it is now clear to us in the 21st century, that something new and big had appeared — a new biological and geological force. A number of scientists (Richard Klein, Ian Tattersall, William Calvin, among many others) think that the “something” that happened 50,000 years ago was the invention of language. Up until this point, humanoids were smart. They could make crude tools in a hit or miss way and handle fire – perhaps like an exceedingly smart chimp. The African hominin’s growing brain size and physical stature had leveled off its increase, but evolution continued inside the brain. “What happened 50,000 years ago,” says Klein, “was a change in the operating system of humans. Perhaps a point mutation effected the way the brain is wired that allowed languages, as we understand language today: rapidly produced, articulate speech.” Instead of acquiring a larger brain, as the Neanderthal and Erectus did, Sapien gained a rewired brain. Language altered the Neanderthal-type mind, and allowed Sapien minds for the first time to invent with purpose and deliberation. Philosopher Daniel Dennet crows in elegant language: “There is no step more uplifting, more momentous in the history of mind design, than the invention of language. When Homo sapiens became the beneficiary of this invention, the species stepped into a slingshot that has launched it far beyond all other earthly species.” The creation of language was the first singularity for humans. It changed everything. Life after language was unimaginable to those on the far side before it.

Language accelerates learning and creation by permitting communication and coordination. A new idea can be spread quickly by having someone explain it and communicate it to others before they have to discover it themselves. But the chief advantage of language is not communication, but auto-generation. Language is a trick which allows the mind to question itself. It is a magic mirror which reveals to the mind what the mind thinks. Language is a handle which turns a mind into a tool. With a grip on the slippery aimless activity of self-reference, self-awareness, language can harness a mind into a fountain of new ideas. Without the cerebral structure of language, we can’t access our own mental activity. We certainly can’t think the way we do. Try it yourself. If our minds can’t tell stories, we can’t consciously create; we can only create by accident. Until we tame the mind with an organization tool capable of communicating to itself, we have stray thoughts without a narrative. We have a feral mind. We have smartness without a tool.

A few scientists believe that, in fact, it was technology that sparked language. To throw a tool – a rock or stick – at an animal and hit it with sufficient force to kill it requires a serious computation in the hominin brain. Each throw requires a long succession of precise neural instructions executed in a split second. But unlike calculating how to grasp a branch in mid-air, the brain must calculate several alternative options for a throw at the same time: the animal speeds up, or it slows down; aim high, aim low. The mind must then spin out the results to gauge the best possible throw before the actual throw – all in a few milli-seconds. Scientists like neurobiologist William Calvin believe that once a brain evolved the power to run multiple rapid throw scenarios, it hijacked this throw procedure to run multiple rapid sequences of notions. The brain would throw words instead of sticks. This reuse or repurposing of technology then became a primitive but advantageous language.

The slippery genius of language opened up many new niches for spreading tribes of Sapiens. They could quickly adapt their tools to hunt or trap an increasing diversity of game, and to gather and process an increasing diversity of plants. There is some evidence that Neanderthals were stuck on a few sources of food. Examination of Neanderthal bones show they lacked the fatty acids found in fish and the Neanderthal diet was mostly meat. But not just any meat. Over half of their diet was woolly mammoth and reindeer. The demise of the Neanderthal may be correlated with the demise of great herds of these megafuana.

Sapiens thrived as broadly omnivorous hunter-gatherers. The unbroken line of human offspring for hundreds of thousands of years proves that a few tools will capture enough nutrition to create the next generation. We are here now because hunting-gathering in the past worked. Several analysis of historical hunter-gather diets show that they were able to secure enough calories to meet the US FDA requirements for folks their size. For example, the Dobe gathered on average 2,140 calories. Fish Creek tribe, 2,130. Hemple Bay tribe, 2,160. They had a varied diet of tubers, vegetables, fruit and meat. Based on studies of bones and pollen in their trash, so did the early Sapiens.

Thomas Hobbe claimed the life of the savage – and by this he meant hunter-gatherers — was “nasty, short and brutish.” But while the life of an early hunter-gatherer was short, and interrupted by nasty warfare, it was not brutish. With only a slim set of a dozen primitive tools humans not only secured enough to survive in all kinds of environments, but these tools and techniques will also afford them some leisure doing so. Anthropological studies confirm that hunter-gathers do not spend all day hunting and gathering. One researcher, Marshall Sahlins, concluded that hunter-gatherers worked only 3-4 hours a day on necessary food chores, putting in what he called “banker hours.” The evidence for his surprising results are controversial: much of the research (by others) was based on time studies of groups who were previously hunting and gathering and returned to this mode only for a few weeks to demonstrate their efficiency. And the measurements lasted only a few weeks. Surveys of other tribes’ yields gave daily calorie intakes of only 1,500 or 1,800 per day for their few hours of work. Furthermore the definition of what activities should be included as the work of food getting is not clear. For instance if a modern human goes shopping at a supermarket — to get food of course — is that classified as “work” time? Why not? Do the elaborate preparations for a community feast where food is exchanged, common to most forager tribes, count as food getting? All these variables shift the measure of how much work it takes to live as a hunter-gatherer with a low dose of technology.

A more realistic and less contentious average for food gathering time among contemporary hunter-gatherer tribes based on a wider range of data is about 6 hours per day. That 6 hour/day average belies a great variation in day to day routine. One to two hour naps or whole days spent sleeping were not uncommon. As one anthropologist noted, when foragers set out to work, “they certainly did not approach it as an unpleasant job to be got over as soon as possible, nor as necessary evil to be postponed as long as possible.” Outside observers almost universally noted the punctuated aspect of work among foragers. Gatherers may work very hard for several days in a row and then do nothing in terms of food getting for the rest of the week. This cycle is known among anthologists as the “paleolithic rhythm” — a day or two on, day or two off. An observer familiar with the Yamana tribe – but it could be almost any hunter tribe — wrote: “Their work is a more a matter of fits and starts, and in these occasional efforts they can develop considerable energy for a certain time. After that, however they show a desire for an incalculably long rest period during which they lie about doing nothing, without showing great fatigue.” The paleolithic rhythm actually reflects the “predator rhythm” since great hunters of the animal world, the lion and other large cats, exhibit the same style: hunting to exhaustion in a short burst and then lounging around days afterward. Hunters, almost by definition, seldom go out hunting, and they succeed in getting a meal even less often. The efficiency of primitive tribal hunting, measured in the yield of calories/hour invested, was only half that of gathering. Meat is thus a treat in almost every foraging culture.

Then there are seasonal variations. Every ecosystem produces a “hungry season” for foragers. In higher cooler latitudes, this late-winter/early spring hungry season is more severe, but even in tropical latitudes, there are seasonal oscillations in the availability of favorite foods, supplemental fruits, or essential wild game. In addition, there are climatic variations: extended periods of droughts, floods, storms that can disrupt yearly patterns. This great punctuations over days, season, and years mean that while there are many times when hunter-gatherers are well-fed, they also can – and do – expect many periods when they are hungry, famished and undernourished. Time spent in this state along the edge of malnutrition is mortal for young children and dire for adults.

The result of all this variation in calories is the paleolithic rhythm at all scales of time. Importantly, this burstiness in “work” is not by choice. When you are primarily dependent of natural systems to provide you foodstuffs, working more does not tend to produce more. You can’t get twice as much food by working twice as hard. The hour which the figs ripen can neither be hurried, nor predicted exactly. Nor can the arrival of game herds. If you do not store surplus, nor cultivate in place, then motion must produce your food. Hunter-gatherers must be in ceaseless movement away from depleted sources in order to maintain production. But once you are committed to perpetual movement, surplus and its tools slow you down. In many contemporary hunter-gatherer tribes, being unencumbered with things is considered a virtue, even a virtue of character. You carry nothing, but cleverly make or procure whatever you need when you need it. “The efficient hunter who would accumulate supplies succeeds at the cost of his own esteem”, says Robert Kelley. Additionally the surplus producer must share the extra food or goods with everyone, which reduces incentive to produce extra. For foragers food storage is therefore socially self-defeating. Instead your hunger must adapt to the movements of the wild. If a dry spell diminishes the yield of the sago, no amount of extra work time will advance the delivery of food. Therefore, foragers take a very accepting pace to eating. When food is there, all work very hard. When it is not, no problem; they will sit around and talk while they are hungry. This very reasonable approach is often misread as tribal laziness, but it is in fact a logical strategy if you rely on the environment to store your food.

We civilized modern workers can look at this leisurely approach to work and feel jealous. Three to six hours a day is a lot less then most adults any developed country put in to their labors. Furthermore, when asked, most acculturated hunter-gatherers don’t want any more than they have. A tribe will rarely have more than one artifact, such as an ax, because why do you need more than one? Either you use the object when you need to, or more likely, you make one when you need one. Once used, artifacts are often discarded rather than saved. That way nothing extra needs to be carried, or cared for. Westerns giving gifts to foragers such as a blanket or knife were often mortified to see them trashed after a day. In a very curious way, foragers lived in the ultimate disposable culture. The best tools, artifacts, technology were all disposable. Elaborate hand-crafted shelters were considered disposable. When a clan or family travel they might erect a home for only a night (a bamboo hut or snow igloo) and then abandoned it the next morning. Larger multi-family lodges might be abandoned after a few years rather than maintained. Same for food patches, which are abandoned after harvesting.

This easy just-in-time self-sufficiency and contentment led Marshall Sahlins to declare hunter-gatherers as “the original affluent society.” But while foragers had sufficient calories most days, and did not create a culture that continually craved more, a better summary might be that hunter-gatherers had “affluence without abundance.” Based on numerous historical encounters with aboriginal tribes, they often, if not regularly, complained about being hungry. Famed anthropologist Collin Turnball noted “The Mbuti complain of food shortage, although they frequently sing to the goodness of the forest.” Often the complaints of hunter-gathers were about the monotony of a carbohydrate stable, like mongongo nuts for every meal; what they meant about shortages, or even hunger, was a shortage of meat, and a hunger for fat, and a distaste for periods of hunger. Their small amounts of technology gave them sufficiency for most of the time, but not abundance.

The fine line between average sufficiency and abundance matters in terms of health. When anthropologists measure the total fertility rate (the mean number of live births over the reproductive years) of women in modern hunter-gather tribes they find it relatively low – about 5 to 6 children in total — compared to the 6-8 of agricultural communities. There are several factors behind this depressed fertility. Perhaps because of uneven nutrition, puberty comes late to forager girls at 16 or 17 years old. (Modern females start at 13) This late menarche for women, combined with a shorter lifespan, delays and thus abbreviates the childbearing window. Breastfeeding usually lasts longer in foragers, which extends the interval between births. Most tribes nurse till children are 2 to 3 years old, while a few tribes keep suckling for as long as 6 years. Also, many women are extremely lean and active, and like lean active women athletes in the west, often have irregular or no menstruations. One theory suggests women need a “critical fatness” to produce fertile eggs, a fatness many forager women lack – at least part of the year — because of a fluctuating diet. And of course, people anywhere can practice deliberate abstinence to space children, and foragers have reasons to do so.

Infanticide also contributed to small families. The prevalence of infanticide varied significantly among foraging tribes. It was as high as 30% of children in traditional artic tribes (in the early 1900s), and zero in others, with an average infanticide rate of 21% among the cross-culture sample of tribes anthropologists measured. In some cultures infanticide was biased towards females, perhaps to balance gender ratios, particularly in tribes where men contributed more food to the family than women (which was not the norm). In other tribes infanticide was practiced to space births, as Robert Kelley says, “in order to maximize reproductive success, rather than population control.” In nomadic cultures mothers needed to carry not only their tools and household items, but also their small children. On frequent long migrations to find food a family had to carry all their possessions. For a pregnant woman to carry more than one small child would endangered the older sibling. Better for all to have children spaced apart.

Child mortality in foraging tribes was severe. A survey of 25 hunter-gatherer tribes in historical times from various continents revealed that on average 25% of children died before they were one, and 37% died before they were 15. In one traditional hunter-gather tribe child mortality was found to be 60%. Most historical tribes have a population growth rate of approximately zero. This depression is made evident, says Robert Kelley in his survey of hunter-gathering peoples, because “when formerly mobile people become sedentary, the rate of population growth increases.” All things equal, the constancy of farmed food breeds more people.

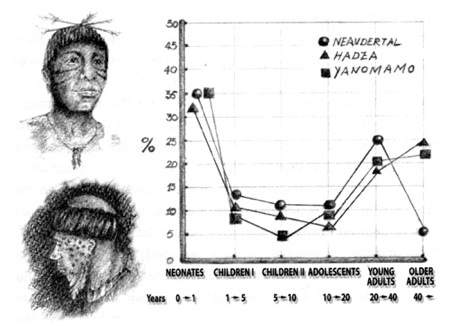

While many children died young, hunting-gather elders did not have it much better. There are no known remains of a Neanderthal who lived to be older than 40. Because extremely high child mortality rates depress average life expectancy, if the outlier oldest is only 40, the median age of a Neanderthal was less than 20. It was a tough life. Based on an analysis of bone stress and cuts, one archeologist said the distribution of injuries on the bodies of Neanderthal were similar to those found on rodeo professionals -– lots of head, trunk and arm injuries like the ones you might get from close encounters with large angry animals. Erik Trinkaus discovered that the pattern of age-related mortality for hunter-gatherers and Neanderthal were nearly parallel, except historical foragers lived a little longer.

Mortality rates expressed as percentage of the population who died in a stage of life. From “The Neanderthal’s Necklace“

A typical tribe of hunters-gatherers had few very young children and no old people. This demographic may explain a common impression visitors had upon meeting intact historical hunter-gatherer tribes. They would remark that “everyone looked extremely healthy and robust.” That’s in part because most everyone was in the prime of life between 15 and 35. We might have the same reaction visiting a city or trendy neighborhood with the same youthful demographic. We’d call them young adults. Tribal life was a lifestyle for and of young adults.

A major effect of this short forager lifespan was the crippling absence of grandparents. Given that women would only start bearing by 17 or so, and die by their thirties, it would be common for parents leave their children in their tweens. We tend to think that a shorter lifespan is rotten -– for the individual -– and no doubt it is. But a short lifespan is extremely detrimental for a society as well. Because without grandparents, it becomes exceedingly difficult to transmit knowledge over time. Grandparents are the conduit of culture, and without them, culture stagnates.

Imagine a society that not only lacked grandparents but also lacked language –- as the pre-Sapiens did. How would learning be transmitted over generations? Your own parents would die before you were an adult and in any case, they could not communicate to you anything beyond what they could show you while you were immature. You would certainly not learn anything from anyone outside your immediate circle of peers. Innovation and cultural learning cease to flow.

Language upended this tight constriction by enabling both an idea to form, and then to be communicated. An innovation could be hatched and then spread across generations via children. Sapiens gained better hunting tools (like thrown spears which permitted a lightweight human to kill a huge dangerous animal from a safe distance), better fishing tools (barbed hooks and traps), and using hot stones to cook not just meat but to extract more calories from wild plants. And they gained all these within only 100 generations of using language. Better tools meant better nutrition.

The primary long-term consequence of this slightly better nutrition was a steady increase in longevity. Anthropologist Rachel Caspari studied the dental fossils of 768 hominin individuals from 5 million years ago, till the great leap, in Europe, Asia and Africa. She determined that there was a “dramatic increase in longevity in the modern humans” about 50,000 years ago. Increasing longevity allowed grand parenting, or what is called the “grandmother effect”: In a virtuous circle, via the communication of grandparents and culture, ever more powerful innovations were able to lengthened life spans further, which gave more time to invent new tools, which increased population. Not only that, increased longevity, “provides a selective advantage promoting further population increase,” because a higher density of humans increased the rate and influence of innovations, which contributed to increased populations. Caspari states that the most “fundamental biological factor that underlies the behavioral innovations of modernity is the increase in adult survivorship.” Increased longevity is probably the most measurable consequence of the acquisition of technology, and it is also the most consequential.

By 20,000 years ago, as the world was warming up and its global ice caps retreating, Sapien’s population and tool kit expanded hand-in-hand. Sapiens used 40 kinds of tools, including anvils, pottery, and composites – complicated spears or cutters made from multiple pieces, such as many tiny flint shards and a handle. While still primarily a hunter-gatherer Sapiens also dappled in sedentism, returning to care for favorite food areas, and developed specialized tools for different types of ecosystems. We know from burial sites in the northern latitudes at this same time, that clothing also evolved from the general (a rough tunic) to specialized items such as a cap, a shirt, a jacket, trousers and moccasins. Henceforth the variety of human tools would become ever more specialized.

The variety of Sapiens tribes exploded as they adapted into diverse watersheds and biomes. Their new tools reflected the specifics of their homes; river inhabitants had many nets; steppe hunters many kinds of points; forest dwellers many types of traps. Their language and looks were diverging.

Yet they shared many qualities. Most hunter-gatherers clustered into family clans that averaged about 25 related people. Clans would gather in larger tribes of several hundred at seasonal feasts or camping grounds. One function of the tribes was to keep genes moving through intermarriage. Population was spread thinly. The average density of a tribe was less than .01 person per square kilometer in cooler climes. The 200-300 folk in your greater tribe would be the total number of people you’d meet in your lifetime. You might be aware of others outside of them because items for trade or barter could travel 300 kilometers. Some of the traded items would be body ornaments and beads, such as ocean shells for inlanders, forest feathers for the coast dwellers. Occasionally pigments were swapped for face painting, but these could also be applied on walls, or applied to carved wood figurines. The dozen tools you carried would have been bone drills, awls, needles, bone knives, a bone hook for fish on a spear, some stone scrapers, maybe some stone sharpies. A number of your blades would be held by bone or wood handles, hafted with cane or hide cord. When you crouched around the fire, someone might play a drum or bone flute. The handful of your possessions might be buried with you when you die.

But don’t take this for harmony. Within 20,000 years of the great march out of Africa, Sapiens helped exterminate 270 out of the 279 then existing species of megafuana. Sapiens used new innovations such as the bow and arrow, spear, and cliff-stampedes to kill off the last of the mastodons, mammoths, moas, woolly rhinos, giant camels — basically every large package of protein that walked on four legs. More than 80% of all large mammal genera on the planet were completely extinct by 10,000 years ago. Somehow four species escaped this fate in North America: the bison, moose, elk and red deer.

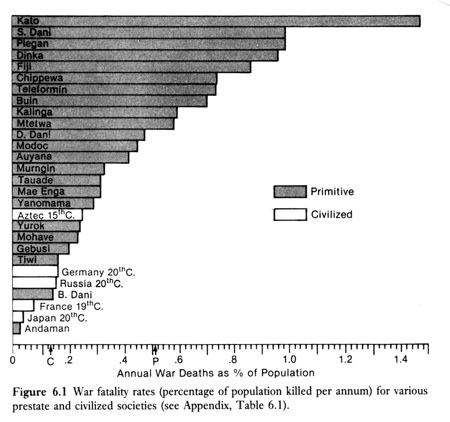

Violence between tribes was endemic as well. The rules of harmony and cooperation that work so well among members of the same tribe, and are often the subject of envy of modern observers, do not apply to those outside of the tribe. Tribes would go to war over waterholes in Australia, or hunting grounds and wild-rice fields in the plains of the US, or river and ocean frontage along the coast in the Pacific Northwest. Commonly, without systems of arbitration, or even leaders, small feuds over stolen goods, or women, or signs of wealth such as pigs in New Guinea, could grow into multigenerational warfare. The death rate due to warfare was 5 times higher among hunter-gatherer tribes than in later agricultural-based societies (0.1% of the population killed per year in “civilized” wars versus 0.5% in war between tribes). Actual rates of warfare varied among tribes and regions, because as in the modern world, one belligerent tribe could disrupt the peace for many. But in general the more nomadic a tribe was, the more peaceful, since it would simply flee from conflict. But when fighting broke out it was fierce and deadly. When the numbers of warriors on both sides were about equal, primitive tribes usually beat the armies of civilization. The Celtic tribes defeated the Romans, the Tuareg smashed the French, the Zulus trumped the British, and it took the US Army three centuries to defeat the Apache tribes and only then because the Army hired traitor Apaches to quell their brothers. As Lawrence Keeley says in his survey of early warfare in War Before Civilization, “The facts recovered by ethnographers and archaeologists indicated unequivocally that primitive and prehistoric warfare was just as terrible and effective as the historic and civilized version. In fact, primitive warfare was much more deadly than that conducted between civilized states because of the greater frequency of combat and the more merciless way it was conducted…It is civilized warfare that is stylized, ritualized, and relatively less dangerous.”

From “War before Civilization“.

Before the singularity of language 50,000 years ago, the world lacked significant technology. For the next 40,000 years (four times as long as civilization has been around) every human who lived was a hunter-gatherer. During this time an estimated 1 billion people explored how far you could go with a handful of tools. This world without much technology provided “enough.” There was leisure and satisfying work for humans. Happiness, too. Without technology, the rhythms and patterns of nature were immediate. Nature ruled your hunger and set your course. Nature was so vast, so bountiful and so close, few humans could separate from it. The attunement with the natural world felt divine. Yet, without technology, the recurring tragedy of child death was ever present. Accidents, warfare and disease meant your life, on average, was far less than half what it could have been. Maybe only a quarter of the natural lifespan you genes afforded. Hunger was always near.

But most noticeably, without technology, your leisure was wasted. You had much time for repetitions, but none for anything new. Within narrow limits you had no bosses. But the direction and interests of your life were laid out in well-worn paths. The cycles of your environment determined your life.

Turns out, the bounty of nature, though vast, does not hold all possibilities. The mind does, but it had not been fully unleashed yet. A world without technology had enough to continue life but not enough to transcend it. The mind, liberated by language, and enabled by the technium, transcended the constraints of nature, and opened up greater realms of possibility. There was a price to pay for this transcendence, but what we gained was civilization and progress.

Those would disappear instantly if technology were to disappear. If a Technology Removal Beam swept across the earth and eliminated every scrap of invention from the world, and sent us into a world without technology – the bus ride no one wants to take – it would shake our foundations. Once the Beam pulverized all hunks of metal, metallic pieces, and slivers of iron and steel into rock dust, and vaporized all plastic, and of course zapped all electronics and modern medicines, and eroded highways and bridges till they disappeared into the landscape without a trace, then the first thing we’d want to do is re-manufacture some hand tools. But if the Technology Removal Beam prevented any constructed tools at all, humans, and humanity, would rapidly be endangered.

After the vast asphalt parking lots of suburban malls melted away, and the greasy blocks of industrial factories subsided beneath the dirt, and the endless sprawl containing hundreds of millions of homes vanished in dust, there would still not be enough bounty in the regrown wilds to sustain 6 billion foragers. For one, the hugely productive herds of megafuana that supported millions of earlier hunters are gone for good. We devoured their easy pickings 20 millennia ago, and removing technology won’t return them. For another the current global population of humans spread equally across all land mass on the planet, including the least hospitable areas of icy mountains and empty desert, would be 10 persons per square kilometer, which is several times more than the average density of sustainable foraging. Thus even a pristine environment could not support 6 billion Sapiens at the meager level of a hunter-gather.

Not that we’d last long anyway. Deprived of gun, spear, and knife, humans would no longer be the key predator. We in fact become prey. Any human lucky enough to eat well would become a desirable meal for newly revived packs of wolves and other alpha predators. The stress and inadequate nutrition of subsistence foraging would revert women’s fertility to its earlier low rate. The growth rate of Homo sapiens would head quickly towards zero. The entirety of the species would retreat to a few remote havens, much as gorillas and chimpanzees have done.

We are not the same folks who marched out of Africa. Our genes have co-evolved with our inventions. In the past 10,000 years alone, in fact, our genes have evolved 100 times faster than the average rate for the previous 6 million years. This should not be a surprise. In the same period we domesticated the dog (all those breeds) from wolves, and cows and corn and more from their unrecognizable ancestors. We, too, have been domesticated. We have domesticated ourselves. Our teeth continue to shrink, our muscles thin out, our hair disappear, our molecular digestion adjust to new foods. Technology has domesticated us. As fast as we remake our tools, we remake ourselves. We are co-evolving with our technology, so that we have become deeply co-dependent on it. Sapiens can no longer survive biologically without some kind of tools. Nor can our humanity continue without the technium.

In a world without technology, we would not be living, and we would not be human.