Tools for Vizuality

Vizuality is visual literacy. In theory, we should be able to annotate, reference and hyperlink moving images as easily as we do text. But all that is hard to do that now. Just try hyperlinking to a specific frame in a movie. You are lucky to be able to link to a small clip. What you’d really like to do is link to an object within a frame as it persists over a scene. Let’s say you want to link to a fez in a scene from Casablanca. No one can’t do that now.

But we should be able to do that. If we had the tools of vizuality to the same degree we have tools of literacy – like cut and paste, footnotes, summaries, dictionaries and the like — creating a link to a fez or bow tie in a film or video would be no problem.

I’ve been gathering experiments for annotating, referencing, hyperlinking, and footnoting specific scenes in moving pictures. One technical name for these procedures is video markup.

A very simple video markup implementation for linking to a scene is Moviestamper. It’s a hack for referring to an exact frame of a movie. Film enthusiasts post their comments on the Moviestamper website for a particular scene in a movie by hanging it on the internal time stamp on the DVD version. For example, a scene in Minority Report in which Tom Cruise gets his eyeballs replace would be annotated on this website at time stamp 1:08:56 like this:

You can thus search for “tags” within movies. Say all references to “aliens” or all displays of blackmail, etc. This annotation is only indirectly linked to the movie; in other words you have to switch back and forth from the film and the website. But you get the idea.

Another thing you’d like to do with moving images is to respond to video with video, just as you might have a string of comments in a conversation. One mark of success in the YouTube universe is to earn video spoofs, parodies, and knock-offs of your posted video. These replies form a kind of dialog. Often there will be a cascade of replies as a particularly good parody will provoke its own parody. (See the Angry Hitler pool of videos). However it is not easy to follow the thread of these responses and responses to responses. One solution to tracking a video dialog is TimeTube. This site will arrange all videos it finds for a particular search term in chronological sequence — in a time line — with those videos with the most views elevated or enlarged. At a glance you can see the course of a visual discussion.

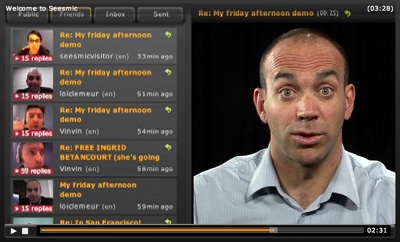

Even better would be a tool to make it easier to post video replies to video in an orderly and structured manner. The new social media website Seesmic offers tools to do just that. After someone posts a video, other vid responses are encouraged and presented in a thread.

In a robust vizuality there is no boundary between text and moving image. Part of the charm of desktop publishing was the refreshing ability to combine text and images. Prior to computers it was very expense and very hairy to overlay text over pictures, or to picturize text, or to paint with text. These alterations required typographic expertise and a long feedback cycle. You had to specified the effect prior to seeing it. No WYSIWYG. It might take days before the graphic professionals could mock up your idea. Marrying text and graphics was rare. Then came page layout programs and Photoshop, and the distinction between text and image was gone.

That boundary is not gone in moving images. The TV screen’s crude resolution made reading text on it a chore. Cinema has always resisted text, even to the point of preferring dubbing foreign languages rather than permitting subtitles. Partly this is because text requires a more user-directed pace, in order to linger over words, or back up. But now that moving images have finally migrated to computer screens, which have the necessary resolution for reading, and the ability to pause and reverse, text and moving images are melding. We finally have TV we can read.

There are good examples of “TV we can read” in the many web-based tutorial sites, where moving images are infiltrated with text instructions. For just one example see the diagram-ish videos at Start Cooking.

No where is the merger of text and moving image more extreme and visible than in the Japanese site Nico Nico Douga. Like many video sites these days, Nico Nico offers a place for amateurs to post their mashups. Japanese fans take music videos, or commercials, or other fan-made videos and recut them into something new. But instead of garnering comments below the mashups (as in YouTube), fans of the Nico Nico mashups add their comments on top of, or inside of the moving images. This produces a garish, bizarre hybrid of video you read.

![]()

Nico Nico has become one of the most popular video sites in Japan. It is off the US social media radar because it in Japanese script and requires users to sign up before any images are visible.

The best entry into this hidden — but exploding — world is via this very informative summary. (Thanks to Robin Sloan for the tip.)

The printing press completed the great move of western civilization from orality to literacy. Later inventions of indexes, bibliographies, concordances, typewriters and 3×5 cards (for random examples) enabled literacy to expand in power until it underpinned our society. Now printed words are so ubiquitous in our environment we don’t even notice them. There is probably not an object in the room you are in without text on it somewhere.

Motion pictures are on their way to become equally ubiquitous. With the arrival of cheap organic LEDs, moving images will soon cover every flat surface. As they do we will march from literacy to vizuality. In order to complete that great transition, we’ll need a whole suite of tools, like these first primitive ones above, which permit us to manipulate, manage, store, cite and create moving images as easily as text.