Your Attention is Cheap: $2.50/per Hour

Our attention is the only valuable resource we personally produce without training. It is in short supply and everyone wants some of it. Since its production is severely limited while everything else is becoming abundant, this scarcity is the foundation of the new economy. Yet for being so precious, our attention is relatively inexpensive. It is cheap, in part, because we have to give it away each day. We can’t save it up, or hoard it. We have to surrender it second by second, in real time.

I tallied up the total number of hours devoted by Americans each year to the major media platforms today using data from the Statistical Abstract of the United States. Cable and satellite TV capture the most of our attention, followed by radio, and then by broadcast TV. These three take the majority of our attention, while the others – books, newspapers, magazines, music, home video, games, and the web – consume only slivers of the total pie.

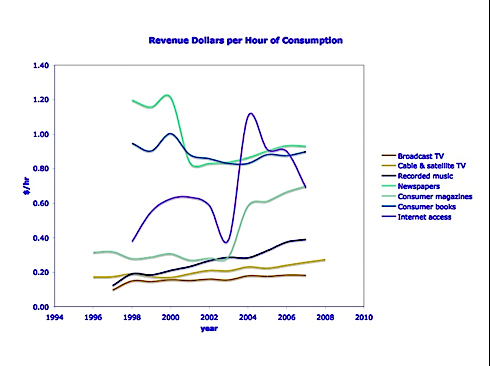

But not all attention is equal. When I tallied up the total annual revenue for each of those industries (when available) and then calculated how much each hour of attention generated in revenues, the answer surprised me.

First, it is a low number. The ratio of dollars-earned by the industry per hour-of-attention-spent by consumers shows that attention is not worth very much to media business. While half a trillion hours are devoted to TV annually (just in the US), it generates, on average, only 20 cents per hour! If you were being paid to watch TV at this rate, you would earn a third-world hourly wage, equivalent to coolie pay for breaking stones into gravel. Newspapers occupy a smaller slice of our attention, but generate more revenue per hour spent with them – about 93 cents per hour. And the internet, remarkably, is increasing its quality of attention each year, garnering more dollars per hour of attention.

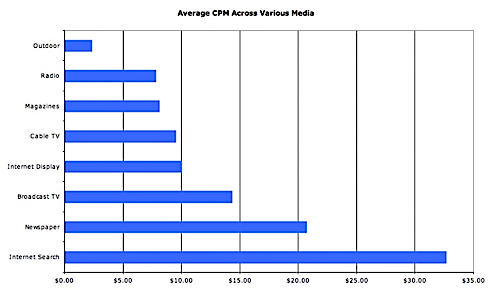

In the advertising business this differential between qualities of attention is often reflected in a metric called CPM, or Cost Per Thousand (M is Latin for thousand). That’s a thousand views, or a thousand readers. This measurement originated in the print business as a way for magazines or periodicals to charge premium prices for material earning greater attention from readers. One luxury publication might demand a CPM of $10, while the local free paper might only get $1. The metric migrated to other media, roughly translating the original “impressions” of printed copies into viewers of shows and hits on websites. Since this cross comparison is a bit of apple-to-oranges, the estimated average CPM of various media platforms range widely. The graph below shows CPM averages (which I compiled from three sources) that range widely, from cheap outdoor billboards to the most expensive AdWords-like ads on search engines like Google.

Newspapers command a premium price for the attention of their readers, while cable TV and radio are worth far less, perhaps because they often run in background mode, sharing attention with something else. However the lead in rates earned by internet search engines is one of the main reasons money of all sorts is steadily flowing to the web. It suggests that people believe that the quality of attention on the web is much higher there (despite all the distractions) than, say, while you are driving on a highway.

But what standard media CPM rates don’t account for, and therefore don’t convey, is the full cognitive spending that a consumer will devote to each impression, or visit, or viewing, or listening. If we multiply each hit or viewing by the amount of time spent on it, we can begin to get a sense of its attention capacity. In a powerpoint presentation Google’s chief economist Hal Varian calculated cost of attention for a 30-second commercial on broadcast TV. In other words, how many minutes of attention in aggregate one dollar buys. An average CPM for TV is $10, or 1 cent per ad impression (one 30-second commercial). In one hour of TV you’ll see at least 10 minutes of commercials, or twenty 30-second spots of ads. Therefore TV broadcasters earn about 20 cents per hour of viewer attention. That’s an identical match with the surprisingly low hourly wage per hour of attention that I found for TV. Television is coolie labor.

A lousy 20 cents per hour of revenue for TV, or even a dollar an hour for upscale newspapers, is surprising because when we look at the costs per hour of use for consumers – how much we have to pay for content — the rates are much higher. Take a book, for instance. The average hardcover book takes 9 hours to read and $36 to buy. Therefore the average consumer cost for that reading experience is $4 per hour. Figure the same costs per hour for a music CD, which may be played many times, or a 2 hour movie that is seen only once for $10.50 in a theater, or $5 per hour. These rates can be thought of as mirroring how much we, as the audience, value our attention.

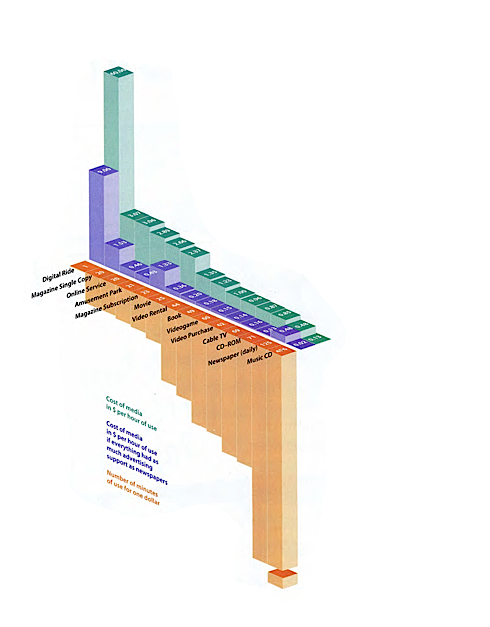

Fifteen years ago I calculated the average hourly costs for various media platforms, including music, books, newspapers, movies and the new thing on the block, digital rides (a kind of virtual reality experience). There was some variation between media, but the price stayed within the same order of magnitude. Remarkably they tended to converge on a fairly uniform mean of $2.00 per hour. In 1995 we tended to pay, on average, two bucks per hour no matter for media use. (Below is the chart that appeared in Wired in 1995.)

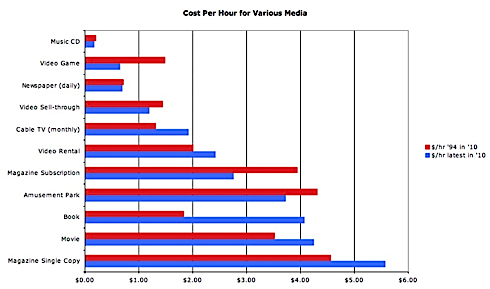

Recently I recalculated the value of our attention for a similar set of media using the same method with this year’s data. The media costs ranged between 50 cents and 5 dollars per hour. Averaged over all media, we tend to spend about $2.50 per hour on media experiences. When I adjusted the 1995 figures for inflation, the average is close to $2.40 in 2010 dollars. That means that the value of our attention is remarkably stable, gaining only a few percent in 15 years. No matter what we are consuming – books, newspapers, movie, music, games — we tend to price it at about $2.50 an hour.

It seems we have some intuitive sense of what a media experience “should” cost, and we don’t stray much from that.

I have no idea why $2.50. That hourly rate is about one third the federal minimum wage. Maybe spending a third of what we earn at work on playing feels right. If media costs $2.50 per media hour, then you could work for 8 hours, deduct your rent and food, and you’d have enough to pay for full-time media consumption for every waking hour outside of work. Happy days! As far as I can tell, this work-sleep-media cycle really is the pattern for many people. But I don’t know if it is really the reason why we intuitively price our attention at the rate we do.

Far more perplexing is why the average hourly price we pay for media is so much higher than the average hourly rate that media earns. We are paying $2.50 per hour to watch or read or listen, but media is earning less than $1.00 per hour for our time, sometimes much less. There’s a gap of $1.50 per hour per capita, which is a lot of money. Where is that extra money going? I am obviously missing something in this analysis. Clearly money follows attention, but not all of the money is arriving where it is expected. Post a comment if you have an explanation.

But as you can see, there are differences in media. We pay more for some than others. We have tended to pay more for movies and magazine and books than other media. This, by the way, is one response to every author’s concern of how low the cost of electronic books might go. I recently wondered on The Technium what might prevent the average cost of an ebook from going to 99 cents. Here is one reason: if we continue to value books more than many other media, like music. Yet if we multiply the average duration of a book (9 hours) by the average cost of $2.50 per hour, we get a price of $22.50. That’s already much higher than the typical Kindle books goes for. So something is amiss. But what if the attention of books is diminishing culturally and their experience is only as valuable as the attention demanded of music, or a newspaper? Then we should multiply its 9-hour duration by 25 or 75 cents, to get a price between $2.25 and $6.75. This would be the price of ebooks if they were valued like music is today. (Music itself could rise or fall in value in the future.)

There’s a bunch of lessons for those of us (foolhardy souls all) hoping to sell media content. When content is priced at under a dollar an hour, you have to move a lot of it to make real money. Luckily there is still trillions of hours of untapped, undervalued attention to go around. Think of the 20 to 30 hours of incredibly intense attention each encounter within a modern console game consumes, but is currently valued as throwaway. Consider the number of hours around the world devoted to YouTube clips, not currently generating money. How about the sizable number of minutes, in aggregate, people spend on Twitter in a year? These are just a few examples of great reservoirs of attention that have not been fully valued yet, but will.

Does all our attention have to be monetized? No, of course not. But whether you choose to sell it or not, it will have a price. And it is not as high as one might think.

While the price may not diverge greatly, some attention is worth more than others. The most valuable attention will be of the meta-variety; paying attention to attention. The more that the full capacity of human attention is mined, gathered, unleashed, and diversified, the more additional attention is needed to navigate through this super abundance. There is no end to the creative ways that attention can be captured, and despite its low cost, no end to the wealth that will be generated by those who follow it because it is all we really have.